New research prompts rethink on chances of life on Uranus moons

SPL

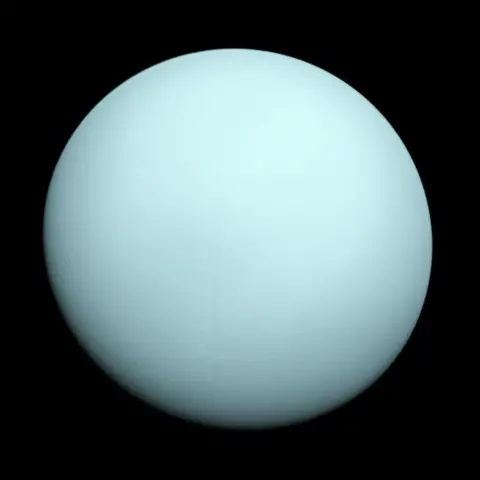

SPLThe planet Uranus and its five largest moons are perhaps not the sterile worlds that scientists have long thought.

Instead, they can have oceans and moons can even be able to support life, say scientists.

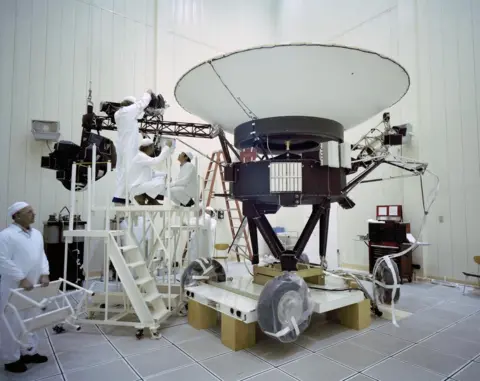

Much of what we know about them has been gathered by the NASA Voyager 2 spacecraft that went almost 40 years ago.

But a new analysis shows that the visit of Voyager coincided with a powerful solar storm, which led to a misleading idea of what the Uranian system is really.

Uranus is a beautiful world sound frozen in the outer parts of our solar system. It is among the coldest of all planets. It is also tilted on the side compared to all the other worlds – as if it had been overthrown – which undoubtedly makes it the strangest.

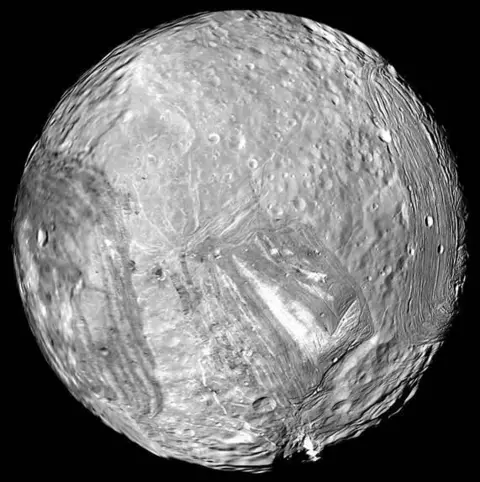

We had our first close look in 1986, when traveling 2 passed and returned sensational photos of the planet and its five large moons.

But what scientists surprised even more is that the data that traveling 2 has returned indicating that the Uranian system was even stranger than they thought.

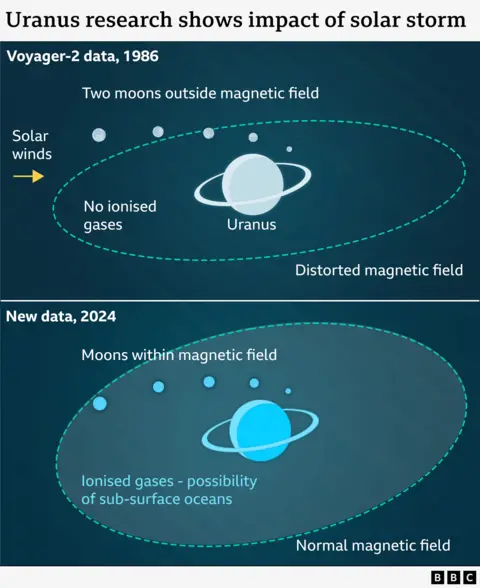

The measures of the instruments of the spaceship indicated that the planets and the moons were inactive, unlike the other moons of the external solar system. They also showed that the protective magnetic field of Uranus was strangely distorted. He was crushed and far from the sun.

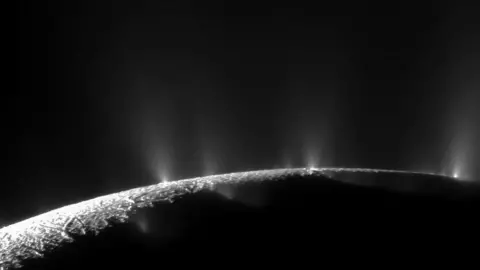

The magnetic field of a planet imprisoned all the gases and other materials that came out of the planet and its moons. These can come from the oceans or geological activity. Traveling 2 found none, suggesting that Uranus and its five largest moons were sterile and inactive.

It was a huge surprise because it was different from the other planets of the solar system and their moons.

Nasa

Nasa Nasa

NasaBut the new analysis has resolved the mystery of several decades. This shows that traveling 2 has gone by a bad day.

The new research shows that just as traveling 2 flew over Uranus, the sun was raging, creating a powerful solar wind that could have blowed the material and temporarily distorted the magnetic field.

So, for 40 years, we have an incorrect vision of what Uranus and his five largest moons normally resemble, according to Dr. William Dunn of the University College of London.

“These results suggest that the Uranian system could be much more exciting than we thought.

Nasa

NasaLinda Spilker was a young scientist working on the Voyager program when Uranus’ data arrived. She is now still as a scientist of the project for travel missions. She said she was delighted to hear about new results, which were published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“The results are fascinating, and I am really delighted to see that there is a life potential in the Uranian system,” she told BBC News.

“I am also very happy that so many things happen with travel data. It is surprising that scientists look at the data we collected in 1986 and find new results and new discoveries. ”

Dr. Affelia Wibisono of the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, which is independent of the research team, described the results as “very exciting”.

“This shows how important it is to come back to the old data, because sometimes, hiding behind them is something new to discover, which can help us to design the next generation of spatial exploration missions”.

This is exactly what NASA does, partly following the new research.

It has been almost 40 years since traveling 2 flew over the icy world and its moons. NASA plans to launch a new mission, the orbit and Uranus probe, to go back for a launch of more than 10 years.

Nasa

NasaAccording to Dr. Jamie Jasinski of NASA, whose data from traveling 2, the mission will have to take into account his results when designing his instruments and planning the scientific survey.

“Some of the instruments of the future spaceship are very designed with ideas for what we have learned to travel 2 when he flew over the system when he lived an abnormal event. We must therefore rethink how we will make discoveries on the new mission so that we can better capture the sciences we need to make discoveries. ”

The NASA Uranus probe should arrive by 2045, which is when scientists hope to know if these remote icy moons, formerly considered as dead worlds, could have the opportunity to be at home.