Bill Moyers Saw What Was Coming

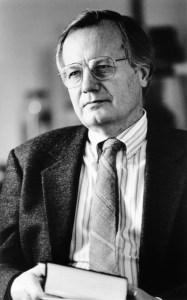

I cannot say for sure when Bill Moyers first developed such a clear eyed-view of the path we were heading down, but I can say that by the time I first started working for him in 2012, as America was clawing its way out of the recession that trailed the 2008 financial crisis, it was already solidly in place.

For decades, Bill, who died last week at the age of 91, was a prominent, relatively mainstream voice like almost no other, warning of the growing gap between America’s rich and poor, the increasing political power of a handful of American oligarchs, and the ever-more-distorted information environment. His hard-hitting dispatches on the concerning state of our reality aired in documentaries and broadcast interviews, often introduced matter-of-factly, following his signature, Cronkite-esque greeting — “Good evening, I’m Bill Moyers,” delivered with an East Texas accent from another era. They continued through both terms of the Bush administration, both terms of the Obama administration, and into the dawn of the first Trump administration. He warned about voter suppression, advancing climate change, and the inability of everyday Americans to achieve the dream of entering, and staying in, the middle class. Finally, he warned that it was all leading us toward a crisis of faith in American institutions that would shake the foundation of our democracy. Ultimately, Donald Trump, he would suggest, was symptom, not cause.

“Let me make it clear that I don’t harbor any idealized notion of politics and democracy,” he said in a 2013 speech to NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, followed by a quip: “I worked for Lyndon Johnson, remember?”

But, he added in that speech, “there is nothing idealized or romantic about the difference between a society whose arrangements roughly serve all its citizens and one whose institutions have been converted into a stupendous fraud. That difference can be the difference between democracy and oligarchy.”

Ultimately, he was right. And not just about that.

In 2001, five years before “An Inconvenient Truth,” he produced a two-hour documentary on Earth’s changing environment, citing global warming as a significant threat. In 2004, three years before the financial crisis, he spoke to future senator Elizabeth Warren — then a Harvard Law professor — about how middle-class Americans were borrowing unsustainably and going bankrupt, and how Congress was failing to come to their aid. “Politicians take note, we’re not making this up,” Bill said in that broadcast. “There’s an invisible crisis building out there.” He repeatedly covered how the North American Free Trade Agreement had shaken the faith of both parties’ voters in the American dream. In 2007, he produced a canonical report on how the mainstream press botched the narrative around the invasion of Iraq. And in 2017, less than a year into Trump’s first term, he put out a documentary in which several women, and one male doctor, shared harrowing stories about their experiences with abortion before Roe was handed down. “We are closer than ever to the reversal of Roe v. Wade, despite the fact that a majority of American adults say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases,” Bill warned. Dobbs came five years later.

It would not be right to say he left us just as our current moment of crisis blossomed into its full, grotesque glory. He was, after all, with us as the march of progress began to falter, as the true bent of history’s long arc started to seem a little less clear. But I do think it’s right to say he saw what we were up against, its contours, more clearly — and, often, decades earlier — than nearly all other public commentators did. He was among the very most persistent voices warning us where we were headed.

Though I did not know Bill Moyers particularly well on a personal level, he was a mentor to me, like he was to many young journalists over many decades. I took an entry level job at his production company, and, over the next several years, worked as a writer, producer or editor for him on various projects. I revered him, and I had a unique window into his approach to covering America during some of his last years in journalism, and as his producers compiled his decades of work for posterity. These years of work shaped my sense of what journalism is, and what our country is — and what both could be.

When I was working for Bill, I was struck, on a near-weekly basis, to discover a new detail about the earlier chapters of his storied career. He had crammed what seemed to be two, possibly three or four, lives into the span of a single life, and was still going strong. That feeling came back to me as I read his obituaries on Thursday; because they largely focused on his astounding number of accomplishments in the decades before I worked with him, I found myself again learning many new facts I had not known about my former boss.

His first entry into public life was as President Lyndon Johnson’s trusted White House aide; he was given a sweeping portfolio, and played a part in shaping the administration’s domestic agenda — what became the Great Society. As the Vietnam War intensified, he became disillusioned and left, starting a new life as a high-profile broadcaster at CBS and publisher at the Long Island newspaper Newsday. His gravitas and commitment to journalistic ideals — as well as, I assume, the fact that he was at CBS — invited comparisons to Edward R. Murrow. As American television began to succumb to the grim fate Murrow had famously warned about years earlier — the era of spineless network execs and a public amusing itself to death — Bill started a third chapter, as an independent, sometimes dissident journalist. “Once upon a time the networks supported muscular investigative reporting into betrayals of the public trust. But democratic values lost out to corporate values when media giants merged news and entertainment and opened the throttle on what Edward R. Murrow called their ‘money-making machine,’” Bill said in a speech at a 2015 journalism award ceremony. “The challenge of journalism today is to survive in the pressure cooker of plutocracy.”

He set as a gold standard the society-altering accomplishments of such progressive era muckrakers as Jacob Riis, Lincoln Steffens and Ray Stannard Baker. He reported with a clarity grounded in his long career as a public servant and journalist. He, after all, had worked alongside or interviewed many of those people who would shape America’s 20th and 21st centuries. But unlike so many in a similar position, he chose to keep power at arm’s length. “What’s important for the journalist is not how close you are to power but how close you are to reality,” he would caution.

His reporting in this chapter of his life, often aired on public television, prompted calls for PBS’s defunding so regularly it’s hard to keep them straight: He annoyed Republicans with his reporting on Iran-Contra. He annoyed them with his reporting on chemical companies’ misdeeds. He annoyed them extensively with his reporting on the Iraq War. He and Bush administration Corporation for Public Broadcasting board chair Kenneth Tomlinson had a storied clash after Tomlinson hired a consultant at an exorbitant fee to examine whether Bill’s shows had a liberal bias; that became part of a growing scandal around Tomlinson’s tenure. The reporting that Tomlinson found so objectionable was, of course, the period when Bill began to weave together the threads that I would — as a 20-something journalist fresh out of grad school, and with little idea of what journalism meant in practice — find so compelling: the threads that helped give some logical scaffolding to America’s fury following the financial crisis, to the rise of Trump, to the smash-and-grab effort by conservative activists and wealthy political donors to abscond with what parts of the state they could during Trump’s first term, and to the ideologues who have thrown in with him to reshape our country in his second.

That brings us to the present, in the midst of rapidly losing so much of what Bill fought for — not just as a political aide at work on the most positive aspects of Johnson’s legacy, but as a journalist.

Of course, Congress has before it now a proposal to defund public broadcasting — more fully than previous Republican functionaries might have dreamed — though that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The increasingly conservative Supreme Court has been chipping away at the Great Society, and the progressive-era foundations on which it was based, for more than a decade. And the second Trump administration has eagerly gotten to work assisting that mission with a sledgehammer, rolling back civil rights protections to their LBJ-era origins, if not further.

Journalism, meanwhile, is struggling to meet the moment, a fact that isn’t entirely an indictment of us journalists. Attention is fractured across a million feeds. America is less inclined today to watch hour-long documentaries of the sort Bill produced; we read books, magazines and newspapers less frequently. We do read posts. “I often hear in my head the late Saul Bellow’s prophecy during an interview I did with him two decades ago. He said the day would come when ‘no one will be heard who does not speak in short bursts of truth,’” Bill said in 2007. “We need to call on our field, our craft, our allies, sympathizers and the public at large to address what is at stake in this new world order — because the market will not deliver to democracy the news we need to survive.” It was another of many prophecies that has come true.

But the point here is not that Bill’s work was all for naught. In fact, one of the great messages of his oeuvre — especially in his final years — is that the work of journalists, and of all citizens in a democracy, is almost definitionally never finished.

In his telling, the best American journalism was and is inextricably bound together with the democratic undertaking, and, specifically, with the ongoing and unfinished project to realize our country’s potential. He spoke in broadcasts and speeches of the American Revolution as an inherently radical event, and the subsequent 250 years as a long struggle by millions of people over generations to make good on its promise. “Ideas have power,” he said in one 2003 speech, “as long as they are not frozen in doctrine. But ideas need legs. The eight-hour day, the minimum wage, the conservation of natural resources and the protection of our air, water, and land, women’s rights and civil rights, free trade unions, Social Security and a civil service based on merit — all these were launched as citizen’s movements and won the endorsement of the political class only after long struggles and in the face of bitter opposition and sneering attacks.”

“Civilization happens because we don’t leave things to other people. What’s right and good doesn’t come naturally. You have to stand up and fight for it — as if the cause depends on you, because it does.”

Accordingly, Bill’s television episodes, speeches and essays were not solely devoted to muckracking. They celebrated the unceasing fight for a better world, and the artists and activists behind it. He appreciated that corruption, bigotry and inequality were endemic. Fighting them was like fighting disease. It would never be fully eradicated. Journalists, activists, and the engaged public must remain vigilant.

He often told a story about one of his earliest experiences in journalism, while working as a teenager at his hometown newspaper in Marshall, Texas. He wrote a series of stories on a dozen or so women in the community who, in his telling, “argued that Social Security was unconstitutional, that imposing it was taxation without representation, and that — here’s my favorite part — ‘requiring us to collect [the tax] is no different from requiring us to collect the garbage.’” These women hired a lawyer, took their fight to court, and lost. (Bill’s articles about them, meanwhile, were picked up by the Associated Press, giving an early boost to his career.)

“I’ve thought over the years about those women and the impact their story had on my life and on my journalism,” he said in a speech in the mid-2000s. “They were not bad people, they were regulars at church, their children were my friends, many of them were active in community affairs and their husbands were pillars of the business and professional class in town. They were respectable and upstanding citizens in all. So it took me a while to figure out what had brought on their spasm of reactionary rebellion.”

“It came to me one day many years later,” he continued. “Fiercely loyal to their families, to their clubs, charities and congregations — fiercely loyal, in other words, to their own kind — they narrowly defined democracy to include only people like themselves.” Many of their own neighbors, he realized, were, to these Social Security skeptics, not as much a part of the democracy as they were. “We the people,” narrowly defined.

“The women who washed and ironed their laundry, wiped their children’s bottoms, made their husbands’ beds and cooked their families’ meals, these women too would grow old and frail, sick and decrepit, lose their men and face the ravages of time alone, with nothing to show from their years of labor but the creases in their brow and the knots on their knuckles,” he said.

While Bill, during the era I worked for him, may not have been a doctrinaire liberal — he harshly criticized Democrats as well as Republicans — he was fiercely committed to combatting through journalism the reactionary and exclusionary strain in America. The throughline from the fights of the progressive era, the New Deal era and the civil rights era — the latter of which he covered closely upon leaving the Johnson administration — was front and center in his work. At one point, he tasked me with closely covering a group of young people suing state and local governments, seeking to force court-ordered climate action to protect their future. It was a fight that legal scholars sometimes dismissed to me as quixotic, especially given the tilt of the Supreme Court. But in their struggle, Bill saw parallels with civil rights cases based on legal theories that were not accepted by the Court — until, one day, they were.

At one point during my time working for him, he interviewed Tom Morello, the former guitarist of Rage Against the Machine who, at the time, had been traveling the country to perform protest songs, including as part of the Occupy movement. “My job is to steel the backbone of people on the front lines of social justice struggles, and to put wind in the sails of those struggles,” Morello told Bill.

This clearly appealed to Bill.

“It’s sort of like people going to church,” replied Bill (who, in addition to his many other life chapters, was an ordained Baptist minister). “They may not know each other very well but when they sing the same songs, same hymn, you can sense something happening to them.”

I am not sure if Bill knew this, though he probably would have endorsed it: for a time, our team began to discuss Morello’s goal as our own objective — to create journalism that, we hoped, would “steel the spines” of those on the front lines of the fight for a better world. Our commitment remained to the facts — everything we did was fact checked, through a complicated system, twice over — and to remain close to reality. But we, like Bill, had our sympathies; we had an idea of who was wrong and right. We did not find these things to be in tension. What’s true often does not fall neatly into the political center; it rarely maps neatly onto politics at all.

I left Bill’s team for Talking Points Memo at the end of 2017, after he announced his intent to retire. (He had been retiring, and unretiring, for more than a decade. That 2017 retirement didn’t totally stick either; he soon began a podcast.) Earlier this year, a former colleague told me Bill was hopping mad about all that was happening. She encouraged me to write him a letter. It took me a few weeks to get my thoughts together, and I eventually typed something out and put it in the mail. By then it was too late.

After his death, I went back and watched some of his recent public appearances. All of the ones I could find came before Trump’s second inauguration. I thought there was an uneasiness in them, an uncertainty about how this was all going to shake out — even during the Biden administration, when America’s fate was a bit less sealed than it seems today. During a 2020 speech to the Chautauqua Institution, an audience member observed that the conclusion of Bill’s half century in journalism “coincides with a serious deterioration in the quality, the production, and the diversity of the fourth estate of democracy” — the press.

“I have missed being on the air the last three years,” Bill began, “in the same way a professional military officer might retire, not knowing that World War III is going to break out next week.” (Watching the video of this, I laughed.) “But in a way I’m relieved because I honestly don’t have the vocabulary to describe to you what this alien force is that has entered our body politic — entered the arteries of our system. And I’m not talking about one man — Trump is a symptom.”

But his public remarks also communicated a grim fortitude. There was one particular sentiment he expressed twice, in two of these final appearances, albeit in different ways. “You can’t quit. You can’t get out of the boat,” he said at a ceremony at the Library of Congress in 2023, as many hundreds of television programs he produced were preserved in an archive there. “Find a place that gives you a sense of being, gives you a sense of mission, gives you a sense of participation, and you will find that the experience of life is more valuable than the meaning of life.” Yes, that was general life advice — you can’t, after all, quit. But that thought, expressed another way in the 2020 Chautauqua speech, takes the valence of advice about the unfinished work of democracy. To paraphrase Abraham Lincoln, there’s always national suicide. But short of that, the only way out is through.

“There’s nothing out there. This is it, folks. There’s not an alternative,” Bill said then. “I’m not going with Musk,” he added, to laughter, gesturing skyward, towards the planets.

“We are all together in this nation and on this planet. You and me: us. And we’re all called to affirm the big ‘we.’”

This, of course, was the “we” those Social Security protestors back in mid-century Marshall, Texas did not understand. It’s what those who opposed the eight-hour day, the minimum wage, women’s rights, civil rights and unions all did not understand. It’s what the rent-seeking oligarchs and petty bigots of 21st century America do not understand.

“Look it up,” Bill concluded. “In the preamble to the Constitution: ‘We the people.’”