Cambridge ‘swimming cap’ brings hope for brain-injured babies

Janine MachineEast of England Technology Correspondent, Cambridge

BBC

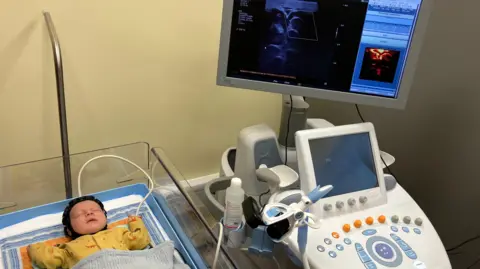

BBCThree-week-old Theo sleeps soundly in a cot, unaware that he is participating in the testing of a new technology that could change the lives of others.

Dr Flora Faure delicately puts a small black cap on him that looks like a swimming cap, or something a rugby striker might wear.

It is covered in hexagonal pieces containing technology that monitors the functioning of his brain.

Researchers at the Rosie Maternity Hospital in Cambridge say they are the first in the world to test a new technique which could speed up the diagnosis and care of children with conditions such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy and learning difficulties.

It could be available in UK hospitals within ten years.

“This is the first time that light and ultrasound have been used together to give a more complete image of the brain,” explains Dr. Faure, researcher in the Fusion study (Functional UltraSound Integrated with Optical Imaging in Neonates).

In the weeks before and after birth, our brains change every day.

Brain damage in newborns is a leading cause of permanent disability, and a program to reduce brain damage during childbirth is currently being rolled out across the NHS.

The injury can affect the brain’s ability to communicate with the body, leading to conditions such as epilepsy, which causes seizures, or cerebral palsy, which affects movement and coordination.

It is more common in premature births, but can be caused by a number of problems, including lack of oxygen, hemorrhage, infections, or birth-related trauma.

But for the five in 1,000 babies who suffer a brain injury, current monitoring methods struggle to predict how and to what extent the child will be affected as they grow.

Explaining how the cap works, Dr Faure says: “Light sensors monitor changes in oxygen around the surface of the brain – a technique known as high-density diffuse optical tomography – and functional ultrasound allows us to image small blood vessels deep in the brain.”

But the device is also different because it’s portable, allowing it to monitor babies more regularly and from the comfort of their cribs.

Dr Alexis Joannides, consultant neurosurgeon, believes this could have several advantages over traditional MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CUS (cranial ultrasound) scans.

“MRI has limitations for two reasons: the first is cost and availability of scanning locations,” he explains.

“The other is you have to take the baby in front of a noisy scanner, wait maybe 20 minutes for the scan, then take the baby back.

“This means that, realistically, you can’t do a series of scans, but in those first few weeks the brain can change on a daily basis, so having a way to do repeated testing is incredibly powerful.”

MRI and CUS are also considered to have limited ability to predict the nature of any impairment due to the complex relationship between brain structure and function, although a study conducted by Imperial College London in 2018 reported that accuracy could be improved with an additional 15-minute scan.

By carrying out regular testing of infants, it is hoped that problems will be identified much earlier and therapies and interventions can begin sooner.

The charity Action Cerebral Palsy welcomed the research.

“For many children with cerebral palsy, the road to diagnosis is long, and families can spend years knowing that their child is ‘at risk’ for developmental problems, but without fully understanding what that means,” says founder Amanda Richardson.

“Technology like this could make a world of difference, but it is important that the capacity of community therapists is built to meet demand, as the wait for help is already long.”

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation TrustProfessor Topun Austin is a consultant neonatologist and director of the Evelyn Perinatal Imaging Center at Cambridge University Hospital. His research focuses on brain processing at the extremes of life – young and old.

He explains: “The Fusion study aims to develop and demonstrate a system for assessing brain activity in newborns and is currently the first of its kind in the world.

“We have spent 12 months successfully proving the concept using healthy, premature babies and will now focus on babies considered to be at higher risk of brain damage.

“Understanding brain activity patterns in term and premature infants can help us identify those most vulnerable to injury at an early stage.”

Theo is one of the healthy full-term babies taking part in the trial, but his mother, Stani Georgieva, believes it is important to contribute.

“His father and I are both scientists and when Theo grows up he will be able to benefit from all the advances made through research, so we thought it was important that he participate a little in this understanding,” she says.

Dr Joannides is also co-director of the NIHR HealthTech Research Center in Brain Injury, based in Cambridge. Its goal is to contribute to the development of new technologies aimed at improving the lives of people suffering from brain injuries.

The center has funded a researcher for the study and will lend their expertise to help roll out the device in the NHS, if the study proves successful.

“We still have some hurdles to overcome, but we hope that within three to five years we will have a product that can be evaluated more widely,” he says.

“If cost allows, it could not only monitor babies with a known problem, but also provide a screening tool to identify others who may be at risk.”