Joan Didion Undone | The Nation

Books & the Arts

/

July 2, 2025

Notes to John, posthumously published journal entries chronicling Didion’s therapy sessions, is a peek into the myths and fears that animated her writing life.

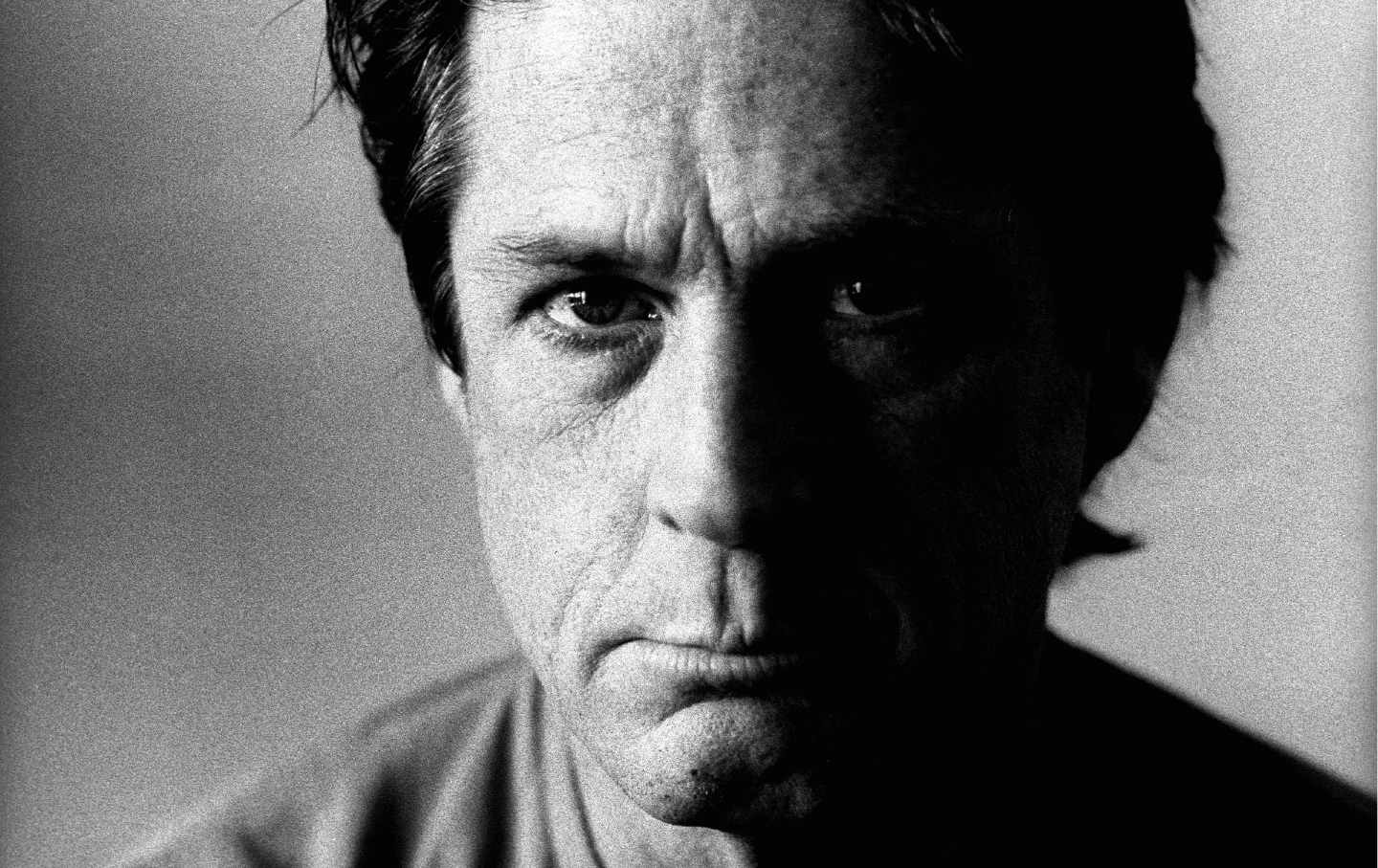

Joan Didion, 2007.

(Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

In 1976, Joan Didion was sent by Rolling Stone to cover the trial of the newspaper heiress Patty Hearst. Hearst was being tried in San Francisco for her involvement in a bank heist carried out two years earlier by her captors, members of the left-wing Symbionese Liberation Army. Didion appeared the perfect woman to report this story. The author had cemented herself as a prominent critic of the postwar counterculture and a new hollowness in American life taking root on the West Coast. Didion saw in the bead-wearing hippies of Haight-Ashbury not collective enlightenment or a shared idealism but a dark-sided incoherence; in the freeways of Southern California she did not discern a formidably engineered togetherness but a gateway to sun-bleached escapism. Hearst was a convenient symbol of generational confusion and genteel excess, making her an almost prepackaged Didion subject—the kind of character that the author routinely lambasted in both her journalism and her fiction.

Didion’s few days at the trial never did turn into that Rolling Stone piece. “I thought the trial had some meaning for me because I was from California,” Didion writes in a short preface to her thoughts on the event, published as “California Notes” in 2017’s South and West. “This didn’t turn out to be true.” The notes hardly mention Patty Hearst or the trial, and instead read as a panicked rehearsal of Didion’s California credentials—the occasionally contradictory hallmarks that establish her as a native daughter. She recalls that the clothes chosen for her as a child “had a strong element of the Pre-Raphaelite, the medieval,” as the life she was “raised to admire was infinitely romantic.” And yet she also recalls “moping around Berkeley,” as a lonely and provincial university student, in her “sneakers and green raincoat,” hungry for the faraway cosmopolitanism of anyplace else. She recalls, too, what she learned at the Sacramento Union copy desk: that “Eldorado County and Eldorado City are so spelled but that regular usage of El Dorado is two words.”

What to make of this memory? Perhaps that such linguistic conventions are emblematic of the self-reinvention, and subsequent cultural bastardization, of the pioneer stock from which Didion descends. Or maybe, as the author seems to conclude after recording further fractured blips—walking the Golden Gate Bridge in high heels; her “first grown-up dress,” of silk jersey, purchased by her grandmother at a Sacramento department store—these recollections comprise a collage of pointless errata. Later in “California Notes,” Didion offers this concession:

At the center of this story is a terrible secret, a kernel of cyanide, and the secret is that the story doesn’t matter, doesn’t make any difference, doesn’t figure. The snow still falls in the Sierra. The Pacific still trembles in its bowl. The great tectonic plates strain against each other while we sleep and wake. Rattlers in the dry grass. Sharks beneath the Golden Gate.

Didion’s defeat, in trying to weave a cohesive narrative out of the yarns of her upbringing and those of Patty Hearst’s fate, is explicit and apparently terminal. But more instructive is the slip of her logic that underpins this surrender. Here, without her usual resolve to outwit certain regional tics by naming them, Didion exposes her own unquestioning reproduction of a psychology (endemic in Californians) that places deference on a terrain above all else; instances of individual feeling or significance—if not destroyed by drought, quake, fire, or flood—are rendered moot. What does it matter what awards one won at a Sacramento grade school or one’s tenure as a “pom-pom girl” when the granite peaks are so high and the fields so parched? By this logic, it’s no wonder that one of Didion’s central fixations is existential futility, the meaninglessness of life. Motifs break; metaphors and similes buckle under the weight of overdetermination like an aqueduct on a fault line; snapshots amass but do not add up to a full portrait. “The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself,” she writes in an essay from Slouching Towards Bethlehem that is quoted widely on Instagram each fire season.

In 1982, still dogged by the unfinished story, Didion attempted to settle the Patty Hearst score under the guise of a review of the heiress’s memoir in the The New York Review of Books. In it, she plots out both Hearst’s pioneer ancestry and her own, and offers up the general “overland crossing” story—made notorious by the Donner Party’s lack of success in doing so—as an explanation for Hearst’s will to survive in captivity. Ultimately, Didion saw something of herself in Hearst and could recognize that geography was, in part, destiny: “This was a California girl, and she was raised on a history that placed not much emphasis on why.”

By the time Didion began seeing a psychiatrist, the renowned Freudian analyst Dr. Roger McKinnon, in the winter of 1999, the “not much emphasis on why” had caught up with her in more immediate ways, off the page. During one of her visits, Didion writes, she explained to Dr. McKinnon that what she had drawn from “all those pioneer California stories,” the “crossing the plains story” and the “burying your child on the trail story,” was a coping mechanism. Dr. McKinnon’s insight was that Didion was now “in a situation where [her] survival strategy” wasn’t “working so successfully.”

Didion had begun talk therapy with Dr. McKinnon on the recommendation of another psychiatrist, a Dr. Kass, who was treating Didion’s daughter, Quintana Roo, for alcoholism, depression, and symptoms that likely amounted to borderline personality disorder. According to Dr. Kass, a considerable snag in Quintana’s recovery was her and Didion’s maladaptive connection and Didion could no longer separate her daughter’s recovery from her own need for treatment. Their dynamic is examined across the nearly two years documented in Notes to John, 46 journal entries that recount Didion’s therapy sessions with Dr. McKinnon. Found as a stack of typed-up pages in the author’s office filing cabinet shortly after her death in 2021, Notes figures as an unfiltered and unrestrained glimpse into domestic distress, the unavoidable guilt of motherhood, and the great burden of legacy. Though the title makes reference to Didion’s husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne, what the book captures is a tornado of interdependence between mother and daughter. In a session from September 5, 2000—almost a year into the author’s psychotherapy—Dr. McKinnon offers this assessment:

You and Quintana had been for too long two people in the same skin. You read any failure on her part as a failure on your part. That was too heavy a burden for you to bear. And bearing this responsibility for your happiness was too heavy a burden for her to bear.

The matter of this mother-daughter convergence had come up in Didion’s accounts of earlier sessions—including in the book’s first entry, on December 29, 1999, though that was the sixth session with Dr. McKinnon—with Didion frequently describing how she would “take the temperature on every phone call” with Quintana, attuned in hypervigilant ways to her daughter’s every shift in tone, attempting to gauge how much Quintana had had to drink or whether she had “become depressed to the point of danger.” To this end, many of the entries in Notes to John have to them an uncanny repetition: Lines about Quintana’s having just completed a successful stint at rehab give way to lines about worrisome calls from Quintana in the night, and then back to the top again.

Taken together, these entries spell out the agonizing monotony of parenting a child (or an adult child) who is in trouble, the constant reactivity to woe on loop. But the sessions also illuminate a fear of losing Quintana that long predates the present struggles and that have everything to do with Didion’s habit of externalizing or avoiding crises by attributing them to the landscape and the dangers that lay atop it.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Didion reflects on her fear that she would lose Quintana to a fatal bite from “the hypothetical rattlesnake in the ivy on Franklin Avenue”—at her dilapidated rental mansion that features heavily in 1979’s The White Album—or to “whale watching,” which likely connotes drowning in the choppy Pacific someplace off Dana Point or Monterey Bay. What she’s obfuscating this time, Dr. McKinnon tells her, are her buried feelings around Quintana’s adoption, an unarticulated anxiety that her daughter might decide to “return” to her biological family. Snakes in the grass, the daunting heave of the ocean—these were not just well-worn rhetorical conceits for Didion but legitimate fears of hers that, when prodded, unwound into complex memories about her childhood and the originating sensibilities that permeated her work. Though it was Quintana’s troubles that had driven Didion to the couch, the pivotal exercise of the author’s time with Dr. McKinnon was putting to the Rorschach test her convenient California symbols.

This exercise, as it’s disclosed in a Notes to John entry from February 2000, was almost identical to the one Didion attempted with the Patty Hearst trial, and what I think she hoped to undertake in that abandoned piece:

I said that in the early seventies I had made several attempts to write a book called “Fairy Tales,” the point of which was to look at certain California myths in terms of my family. I had been unable on every attempt to get past about page 30. The problem, I had thought then and still think, was that I was incapable of examining my family—I could have written easily enough about California, but the point here was to look at California mythology as it intersected with my family’s mythology, and I had been finally incapable of doing that.

What’s revealing about this passage is Didion’s admission to the limits of her own thinking; a naked confession of deficit from a writer so religiously insistent on her own subjectivity that her biases often took on the shape of atmospheric truth. The fated absolutism of works like “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”—her famous 1967 essay on Haight-Ashbury’s decadence—helped crystallize Didion’s status as a totemic figure, but Notes shows us a much more uncertain and provisional thinker. Didion’s imperious omniscience, wrought by the nihilistic constructions found in those early works, might then be better cast as the author’s suffocating closeness to her own outlook. Her thinking was, in other words, too imprisoned by the old-world fictions—her unwittingly tight cling to the bygone homesteader ethos on which she was raised—to take sober stock of the world as it appeared around her. Didion, as Notes highlights, suffers a bout of alienation—the same phenomenon that she routinely derided in the hippies and other countercultural subjects during this period.

Notes to John, then, should not be read as an accessory text to The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011). Those two books, taken jointly, reflect on the shattering aftermath of the sudden death of the author’s husband and the “cascade of medical crises” to which Quintana would lose her life at the age of 39. Sure, Notes can be digested as a catalog of the domestic tragedies that presage the grave outcomes she would later write about. But Notes is only a gratifying artifact—or worth the probable ethical impropriety of its publication—insofar as it illustrates how one of America’s most worshipped writers worked, and worked to change her mind.

Talk therapy gave Didion a new language with which to interpret and articulate the lineage of myths, fears, habits, ghosts, ambitions, and tensions that composed her particular psychogeography. She discussed with Dr. McKinnon her mother Eduene’s “distrust of groups”; she discussed letters she found of her father’s, dated 1953 and 1955, that read “almost like suicide notes.” She was becoming “a good deal more open,” and beginning to place “emphasis on why.” At a certain point in her treatment, so reported in an October 2000 entry, the question of “what to do next” writing-wise, namely as it related to picking up the “Fairy Tales” mantle, “had become more urgent.” Didion brought up to Dr. McKinnon, in a handful of sessions, “the California book” and the “book about California,” but in this visit, it occurred to Didion that she could “take a couple of long pieces” she’d “done about California and use them—one in particular—for an extended essay or book about California,” because “the attitudes implicit” in those long pieces had been things that she and Dr. McKinnon had “talked about all year.”

This project was published in 2006 as Where I Was From, which is, if not Didion’s most stylish or oft-quoted work, then certainly her most important. The book is an expansion and a redress of all of Didion’s previous writings about the state and its founding social and political contradictions, this time filled in with more fluent surveys of her family history. (The tossed-off aside about “Pre-Raphaelite” children’s garb from “California Notes” is resuscitated, and the “trembling” Pacific makes a cameo, too.) I am struck now, in revisiting Where I Was From, just how many passages are plucked practically verbatim from the reports found in Notes for John. A memorable section from Notes, detailing a time when Didion’s father, Frank, was receiving psychiatric care for extreme depression at Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco, appears toward the end of Where I Was From with only minor additions and rhetorical interventions: “He could only eat raw oysters” it goes in Notes; in Where I Was From, “I remember that all he would eat that year were oysters, raw.” Even the structure of Where I Was From—reported pieces on, say, the heavily subsidized industrialization of California interlaced with this or that reminiscence about the sometimes-painful ways the Didion family redoubled their frontier romanticism in the face of rapid development—evokes Didion’s newfangled path to psychic integration. Stripped of its usual armor in the form of melodious repetition and other of the techniques that mark Didion’s early style, her “I” here establishes its authority not through cunning tactics but with a hard-won clarity that transcends mere articulation and treats open-mindedness as a testament to deeper understanding.

So many of Didion’s formative works strained against theory and yet still relied on feeling or sensibility to be a flimsy proxy for it. Where I Am From’s formal omnivorousness—close readings of Didion’s and others’ novels, plotted histories, narrativized therapy notes, memoir, statistical reports, and on—helps nudge emotion closer to postulation. And while this new mode proves generative, Didion arrives at much the same conclusion she did in earlier, more fundamentalist texts like Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album: that there’s an inherent violence in change, and when the touchstones that outline one’s existence are constantly destroyed and reimagined, how is one to grasp one’s place in history?

Today the site of the old Letterman Army Hospital is occupied by One Letterman, a sprawling complex that headquarters George Lucas’s film company and several venture capital firms focused on tech. One Letterman’s grounds are meant to “reflect the landscape of the high Sierras,” but inexplicably do so with weeping willows, bird-of-paradise, and English roses. Since I work nearby, I often walk the campus at lunch and overhear groups of men in company-branded vests discussing this or that “disruption” in artificial intelligence. Didion always crosses my mind when I encounter this scene, not just because it sits atop another of her landmarks lost to the violent sweep of change, but because its specific confluence of mismatched flora and pernicious “innovation” seems to reflect the accelerated strangeness of trying to situate oneself in the present. Clearer, in this tableau, is the vision of a future in which our humanity becomes as unintelligible to us as our landscapes. At least, if that happens, there will be no shortage of Didion quotes to post online in hopes of signaling our devastation.

More from The Nation

The Studio is pitched as a send-up of the idiocy of the entertainment industry, but its potshots are harmless, even friendly.

Books & the Arts

/

Vikram Murthi

A conversation with the German sociologist about the challenges that face Europe and his polarizing views on how to roll back the excesses of globalization.

Books & the Arts

/

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

When the Beach Boys front man died, the obituaries described him as a genius. Which means what, exactly?

Sid Holt