A Fired Federal Worker Finds Refuge in Mexico

Feature

/

November 18, 2025

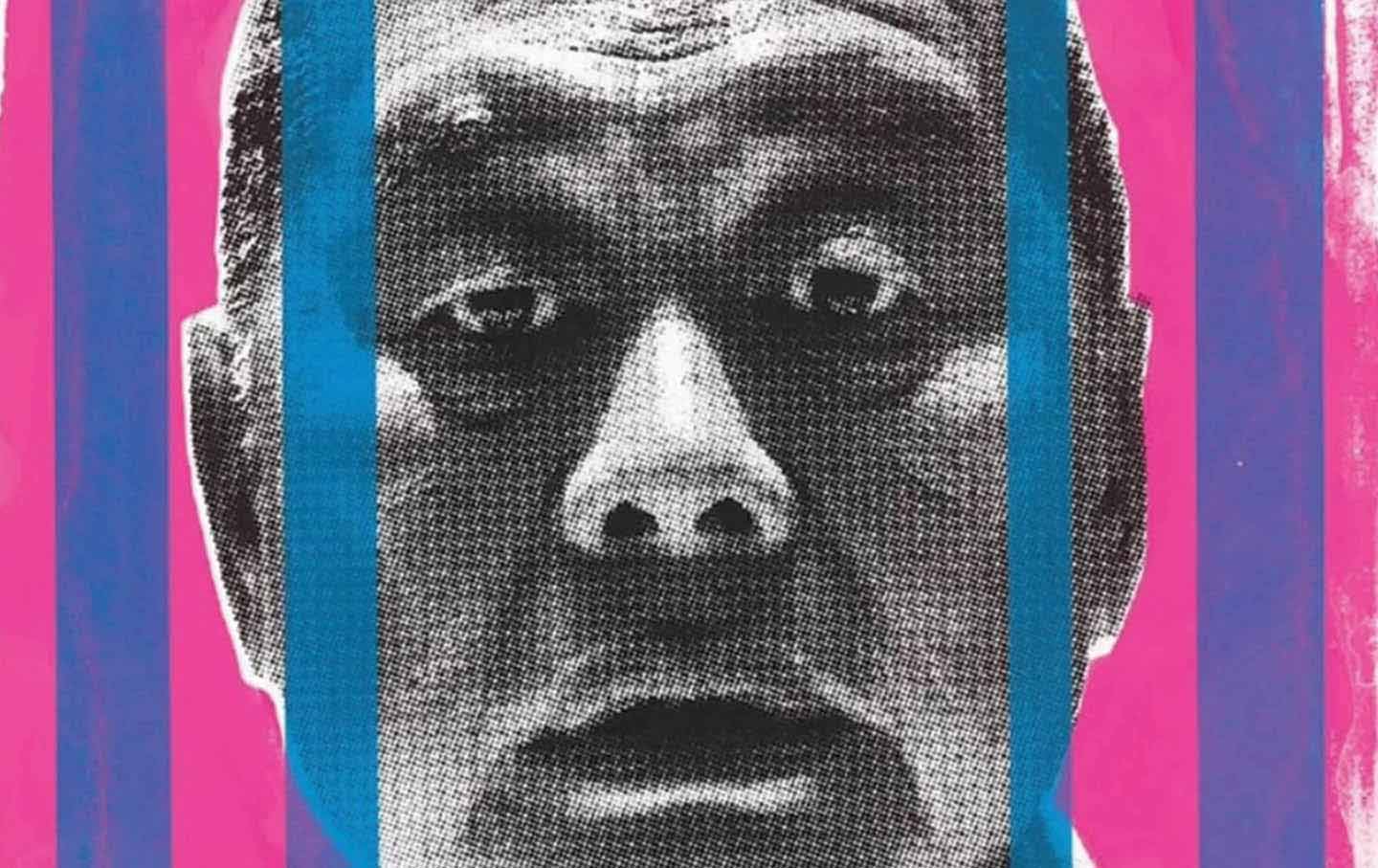

“The administration doesn’t want me. I personally don’t feel safe [in the United States]. I know I’m not the only person who feels that way.”

Within 24 hours of arriving in San Miguel de Allende, Karen decided to permanently leave the United States and become one of the many recent US immigrants to Mexico.

Four months before visiting the city, the 55-year-old had been terminated as part of the Trump administration’s January 20 executive order suspending the US Refugee Admissions Program. Karen, who asked me not to use her full name because of her current immigration status, says through a haze of tears, “It’s hard to explain the compound grief involved in seeing a sector that did nothing but good just destroyed,” adding that much of her work involved the prevention of sexual exploitation.

“The day that I got my notice, 3,000 of my colleagues around the world got their notice,” Karen says from her modest two-floor, two-bedroom apartment in a neighborhood not far from the center of the city. “The people who are coming through the US Refugee Admissions Program, they’ve gone through a minimum of two years of background checks. I can’t even tell you how extensive these checks are.… This idea that there are rapists or whatever coming is just total bullshit. We’re talking about people who waited in refugee camps for 10, 15 years to resettle.”

Current Issue

Karen was born in the US but grew up mostly in Japan, where her father, a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War, fulfilled his alternate service teaching English. Karen is a “third culture kid,” a term coined in the 1950s by the American sociologist Ruth Hill Useem that refers to someone who spends their formative years in a culture different from the one in which their parents were raised.

After attending college and graduate school in the United States, Karen lived mostly in other countries, including Cambodia, Thailand, and Papua New Guinea, where she worked in anti-trafficking programs. She was living in California in 2023 when she took a job as a humanitarian worker contracted with the United Nations in Washington.

During her time in DC, more than 100,000 refugees (many from Afghanistan) were resettled in the US, according to the Migration Policy Institute. It was the highest number of admissions in any single year for the past three decades. “We did that in anticipation that Trump would severely curtail [the program],” Karen says. “We did not think that he would just end a program that had been operating for 20 years.”

It was a long-time friend from her childhood in Japan who told Karen to check out San Miguel. “You can live a lot more cheaply. It’s a wonderful, warm, friendly, welcoming community,” her friend said, adding, “It’s not going to be a cakewalk,” but it was something she could handle.

Karen took him up on the idea in July and found refuge in a $650-a-month apartment in Colonia Guadalupe, a barrio known for its vibrant murals and street art, featuring abstract images and depictions of Huichol mythology.

San Miguel has been a destination for US immigrants since the 1930s. The American artist Stirling Dickinson was part of the first wave of artists drawn to the city, which is famous for its cobblestone streets and for La Parroquia, the towering neo-Gothic church of pink stone in the center of town. In 1951, Dickinson became the director of the Instituto Allende, a cultural hub and art school that attracted a slew of prominent American artists and writers, including the Beat Generation icons Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady, as well as many World War II veterans who used the GI Bill to study art there. In 2008, the city and the nearby Sanctuary of Jesús Nazareno de Atotonilco were designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

“I feel that the community here really understands me, both Mexican and expats,” Karen says, referring to the influx of Americans who’ve relocated to the city since Trump was first elected president in 2016. “My landlord is wonderful, and I explain to him everything that’s going on. Of course, Mexicans are horrified looking at what’s going on in the United States.”

Karen is terrified that she won’t be able to qualify for a permanent resident visa in Mexico, which requires a monthly income of around $6,900 or a bank account balance of at least $279,000. After years of working outside the US and for the UN, she doesn’t qualify for unemployment, and her salaries have always been moderate, but she’s determined to stay where she is and out of America. “The administration doesn’t want me. I personally don’t feel safe there. I know I’m not the only person who feels that way.”

On her trek from Los Angeles to San Miguel, Karen says she saw what appeared to be Mexican Americans on the road driving south in cars pulling trailers piled high with furniture and other personal belongings covered in tarps. “It almost looked like The Grapes of Wrath…. Good on them,” she says.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the US Refugee Admissions Program focused on rescuing victims of sexual exploitation. The fired humanitarian worker focused on prevention in this area, not the program.

More from The Nation

The Americans recently relocating to San Miguel de Allende are a new kind of “expat,” a word they refuse to call themselves.

Rebekah Sager

The international community must decide which principle will prevail: the right of self-determination or the right of conquest.

Stephen Zunes

How a globe-trotting attorney is trying to win the release of the famed Hong Kong publisher.

Feature

/

Liam Scott

They stripped us naked, deprived us of sleep, food, and sanitary facilities, arbitrarily threatened us with guns, and physically attacked us.

Thomas Becker

The systematic violence of American militarism has shaped all our lives, including the soldiers who have come to realize that they were used to perpetrate it.

Kelly Denton-Borhaug

The new film Nuremberg may tell us as much about the present as about the past.

Elizabeth Borgwardt