How the Brain Recovers from Running a Marathon Could Lead to Better MS Treatment

Running a marathon puts stress on your bones, muscles, and tendons — to name a few things. And while you might feel it in your legs and your lungs as you’re running that 26.2-mile race, what you don’t feel is your body starting to eat your brain.

Luckily, however, the effects on your brain are completely reversible, and after two months, return to normal. While this information may deter you from wanting to run a marathon, the discovery, published recently in the journal Nature Metabolism, may actually help treat those with multiple sclerosis (MS).

What Myelin Does for the Brain

Myelin is a fatty substance that protects nerve cells, also known as neurons. It acts as an insulator that helps pass the brain’s electrical pulses between neurons safely and efficiently. However, myelin can also be a source of energy during extreme metabolic conditions, such as running a marathon.

During a marathon, as with other types of long-distance exercise, the body typically relies on its energy stores. This will likely come in the form of carbohydrates, like glycogen in the muscles. However, when the carbohydrates are all burned up, the body will start to rely on fat stores, including the fatty myelin in the brain.

According to the study authors, marathon runners experienced a decrease in myelin in certain brain regions after completing the whole race. However, their myelin levels returned to normal within two months of the race.

Read More: Adult Brains Do Make New Neurons, but Not Always When We Need Them Most

Analyzing Myelin in Marathon Runners’ Brains

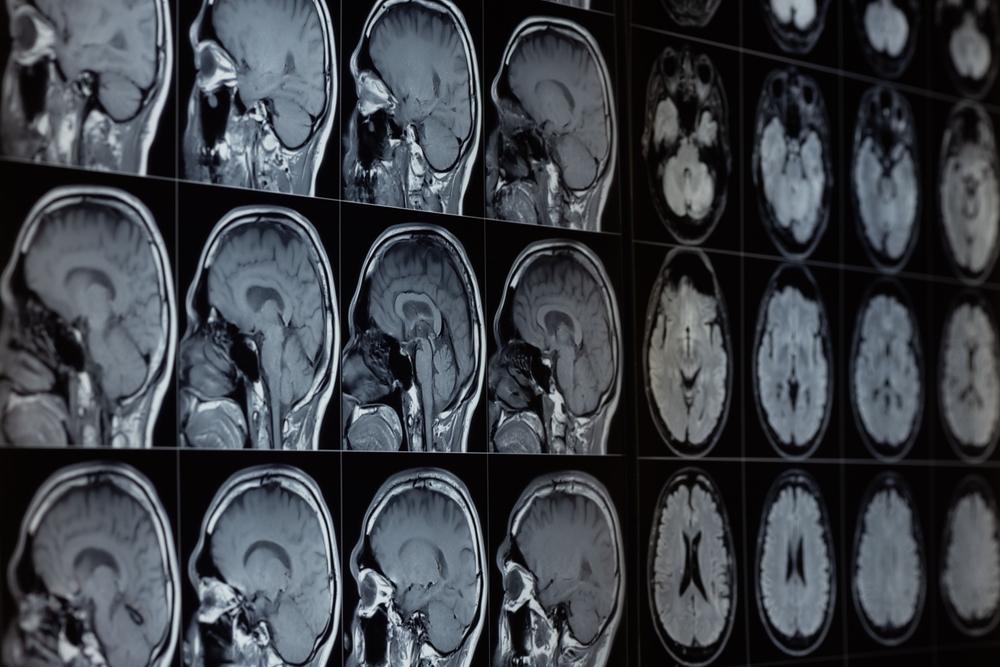

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the research team, including Carlos Matute, Professor of Anatomy and Human Embryology at the UPV/EHU and a researcher at IIS Biobizkaia, Pedro Ramos-Cabrer, Ikerbasque Research Professor at CIC biomaGUNE, and Alberto Cabrera-Zubizarreta, radiologist at HT Médica, looked at images of the runners’ brains 48 hours before the race, two weeks after the race, and then finally two months after the race.

The team analyzed the images of myelin water in the runners’ brains, which can be an indirect indicator of myelin in the brain. Through these images, the team was able to measure the fraction of myelin water and saw “a reduction in the myelin content in 12 areas of white matter in the brain, which are related to motor coordination and sensory and emotional integration,” Matute said in a press release.

The results of the two-week images revealed that “the myelin concentrations had increased substantially, but had not yet reached pre-race levels,” Ramos-Cabrer said in a press release.

However, the two-month image showed that the myelin was once again at pre-race levels.

Running for Multiple Sclerosis

The body consuming a vital area of the brain is shocking. But this new information could be crucial in helping to treat those with MS or other conditions, known as demyelinating diseases, that can damage or deplete myelin.

“Understanding how the myelin in the runners recovers quickly may provide clues for developing treatments for demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, in which the disappearance of myelin and, therefore, of its energy contribution, facilitates structural damage and degeneration,” Matute said in a press release.

You don’t need to stop running marathons, the study authors say, especially since exercise is so beneficial for the body. However, those with demyelinating disease, like MS, may want to avoid these types of exercises, as they can be more harmful.

This article is not offering medical advice and should be used for informational purposes only.

Read More: Is There a Microbe Behind Multiple Sclerosis?

This article is a republished version of this previously published article here

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

A graduate of UW-Whitewater, Monica Cull wrote for several organizations, including one that focused on bees and the natural world, before coming to Discover Magazine. Her current work also appears on her travel blog and Common State Magazine. Her love of science came from watching PBS shows as a kid with her mom and spending too much time binging Doctor Who.