Physicists and philosophers have long struggled to understand the nature of time: Here’s why

When you purchase through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

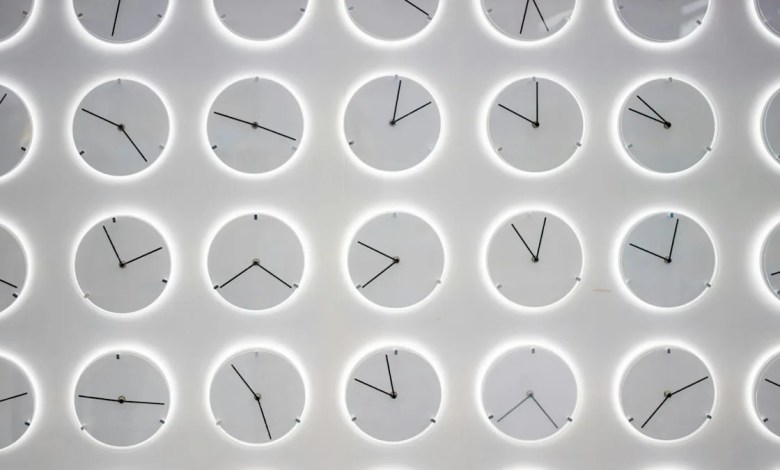

Time itself is not difficult to grasp: we all understand it, despite our persistent struggle to describe it. The problem is one of articulation: an inability to accurately draw the right boundaries around the nature of time, both conceptually and linguistically. | Credit: Donald Wu/Unsplash

This article was originally published on The conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com Expert voices: opinion pieces and perspectives.

THE nature of time has tormented thinkers for as long as we have tried to understand the world in which we live. Intuitively we know what time it is, but try to explain it, and we end up knotting our minds.

Saint Augustine of Hippoa theologian whose writings have influenced Western philosophy, faced a paradoxical challenge in trying to articulate time more than 1,600 years ago:

“What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I want to explain it to someone who asks questions, I don’t know. »

Nearly a thousand years earlier, Heraclitus of Ephesus offered penetrating insight. According to the classical Greek philosopher Plato Cratylus:

“Heraclitus is supposed to say that everything is in motion and nothing is at rest; he compares them to the flow of a river and says that you cannot go into the same water twice.

At first glance, this may seem like another paradox: how can something be the same river and yet not be the same? But Heraclitus adds clarity, not confusion: the river — a thing that exists — changes continually. Although it is the same river, different waters flow at every moment.

Even though the continuous flow of the river creates this plain, so does everything that exists, including the person entering the river. They remain the same person, but each moment they step foot in the river is distinct.

How can time seem so obvious, so woven into the fabric of our experience, and yet remain the bane of every thinker who tried to explain it?

A joint problem

The key question is not one that most physicists would consider relevant. Nor is it a challenge that philosophers have succeeded in solving.

Time itself is not difficult to grasp: we all understand it, despite our persistent struggle to describe it. As Augustine felt, the problem is one of articulation: a failure to accurately draw the right boundaries around the nature of time, both conceptually and linguistically.

Specifically, physicists and philosophers tend to confuse what it means to exist with what it means for something to happen – treating events as if they exist. Once this distinction is recognized, the fog clears and Augustine’s paradox dissolves.

The source of the problem

In fundamental logic, there are no real paradoxes, only deductions that rely on subtly misinterpreted premises.

Shortly after Heraclitus attempted to clarify time, Parmenides of Elea did the opposite. His deduction begins with a seemingly valid premise – “what is, is; and what is not, is not” – then quietly introduces a crucial hypothesis. It states that the past is part of reality because it was experienced, and that the future must also be part of reality because we anticipate it.

Therefore, Parmenides concludes, the past and the future are part of “what is,” and all eternity must form a single, continuous whole in which time is an illusion.

Parmenides’ student Zeno imagined several paradoxes to support this view. In modern terms, Zeno would say that if you tried to walk from one end of a city block to the other, you would never make it. To walk a block, you must first walk half, then half of what’s left, and so on – always halving the remaining distance, never reaching the end.

But of course you can walk to the end of the block and beyond – so Zeno’s deduction is absurd. His error consists of removing time from the table and only considering successive spatial configurations. Its decreasing distances are accompanied by decreasing time intervals, both becoming small in parallel.

Zeno implicitly fixes the overall time available for movement – just as he fixes the distance – and the paradox only arises because time has been removed. Restore time, and the contradiction disappears.

Parmenides makes a similar error in asserting that events of the past and future – things that have happened or will happen – exist. It is this hypothesis that poses the problem: it is equivalent to the conclusion he wants to reach. His reasoning is circular and ends with a restatement of his hypothesis – only in a way that seems different and profound.

What does it mean for the nature of time if spacetime exists? | Credit: Robert Lea (created with Canva)

Space-time models

An event is something that happens at a specific place and time. To Albert Einstein’s theories of relativityspace-time is a four-dimensional model describing all these occurrences: each point is a particular event, and the continuous sequence of events associated with an object forms his world line — its path through space and time.

But events do not exist; they are coming. When physicists and philosophers talk about space-time as something that existsthey treat events as existing things – the same subtle error that has caused 25 centuries of confusion.

Cosmology — the study of the entire universe — provides clear resolution.

It describes a three-dimensional universe filled with stars, planets and galaxies. And during this existence, the locations of each particle at each instance are individual space-time events. As the universe exists, the events occurring in each moment trace world lines in four-dimensional space-time – a geometric representation of everything that happens during this course of existence; a useful model, although it does not exist.

The resolution

Resolving Augustine’s paradox – that time is something we naturally understand but cannot describe – is simple once the source of confusion is identified.

Events – things that happen or happen – are not things that exist. Every time you enter the river is a unique event. This happens over the course of your existence and that of the river. You and the river exist; the moment you enter arrived.

The philosophers were distressed time travel paradoxes for over a century, yet the basic concept relies on the same subtle error — something that science fiction writer HG Wells introduced early in his work. The time machine.

By presenting his idea, the Time Traveler moves from describing three-dimensional objects to objects that exist, to moments along a worldline – and finally to treating the worldline as something that exists.

This last stage corresponds precisely to the moment when the map is confused with the territory. Once the world line, or even space-time, is imagined, what stops us from imagining that a traveler could move along it?

Occurrence and existence are two fundamentally distinct aspects of time: each is essential to fully understanding it, but should never be confused with the other.

Talking and thinking about events as things that exist has been the source of our confusion about time for millennia. Let us now consider time in light of this distinction. Think about the things that exist around you, the familiar stories of time travel, and the physics of space-time itself.

Once you recognize ours as an existing three-dimensional universe, filled with existing things, and that events are occurring every moment during this cosmic existence — cartography to space-time without be reality – everything aligns. Augustine’s paradox dissolves: time is no longer mysterious once occurrence and existence are separated.