Magnetic avalanches on the sun reveal the hidden engine powering solar flares

When you purchase through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

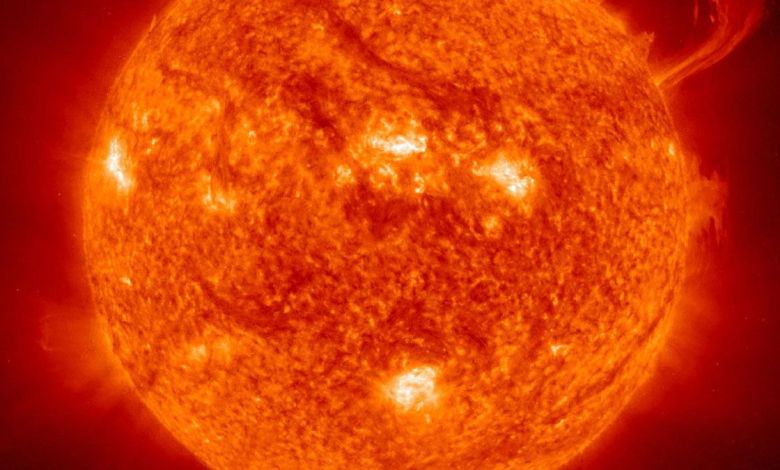

The sun is unleashed with a powerful solar flare. Scientists may now know how these outflows are generated. | Credit: ESA/NASA/SOHO

A giant solar flare on our sun was fueled by an avalanche of smaller magnetic disturbances, providing the clearest insight yet into how our star’s energy is released in a torrent of ultraviolet light and high-energy X-rays. The discovery was made by the European Space Agency (ESA) Solar Orbiter mission, which consists of imaging the sun closer than any spacecraft before it.

Some solar flares can cause coronal mass ejections (CME) – huge plumes of plasma blown out of the solar corona and into deep space. If their trajectory far from the sun crosses EarthDue to the location of these planets, they can trigger geomagnetic storms that can damage satellites and power grids while disrupting communications, and dazzle us with bright colors. auroral lights.

The more we learn about how solar flares are triggered, the better prepared we will be to predict when a dangerous flare and CME is about to occur. The new Solar Orbiter observations are a major step in this direction.

“This is one of the most exciting results obtained so far with Solar Orbiter,” Miho Janvier, ESA project co-scientist on Solar Orbiter, said in a statement. statement. “Solar Orbiter observations unveil the central driver of an eruption and highlight the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism.”

Getting to the bottom of solar flares

On September 30, 2024, Solar Orbiter came within 43.3 million kilometers of the sun, when it witnessed the flare of a medium-class spacecraft. solar flare. With four Solar Orbiter instruments working in unison to observe the eruption, scientists have, for the first time, observed how smaller magnetic instabilities can turn into a large eruption, like an avalanche on a snowy mountainside from a relatively small disturbance.

“We were really lucky to witness the precursor events of this big eruption in such detail,” said lead author of the research Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany. “We were really in the right place, at the right time, to capture every detail of this eruption.”

Solar flares are the product of magnetic reconnection. This is when the magnetic field lines on the sun, mixed with high-energy plasma, strain and break, releasing enormous amounts of energy before the field lines reconnect. The precise origins of solar flares, however, remain secret. Is it a single powerful eruption or an accumulation of smaller reconnection events? For the September 30 eruption at least, Solar Orbiter has found the answer.

Starting with its Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), Solar Orbiter witnessed the generation of the flare over 40 minutes. EUI detected changes in the magnetic environment of the solar corona at the eruption point of the flare, capturing details as small as a few hundred kilometers on timescales of less than two seconds, which corresponds to the time covered by each image.

The spacecraft saw an arcuate filament made of intertwined magnetic fields carrying plasma and connected to a cross-shaped region of magnetic activity intertwined with additional magnetic field lines. He watched as the region became increasingly unstable, field lines breaking and reconnecting, releasing bursts of energy that appeared as bright points of light.

A snapshot of the sun captured by Solar Orbiter moments before a powerful solar flare erupts. | Credit: ESA & NASA/Solar Orbiter/EUI Team

These bursts were the start of the avalanche. They set off a chain reaction of increasingly powerful reconnection events. At some point, the arcing filament broke away from one of its anchor points on the sun and launched into space, blown away by the ferocity of the sun. solar wind. The cascade of smaller reconnection events quickly gained momentum before culminating in a middle-class eruption.

“These minutes before the eruption are extremely important, and Solar Orbiter gave us a window directly onto the foot of the eruption, where this avalanche process began,” Chitta said. “We were surprised to see how much of the big eruption is driven by a series of smaller reconnection events that propagate rapidly through space and time.”

Three other instruments aboard the Solar Orbiter – SPICE (Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment), STIX (X-ray spectrometer/Telescope) and PHI (Polarimetric and Heliosemic Imager) – also observed the eruption, measuring events at different depths in the the atmosphere of the sunfrom the outer atmosphere, the corona, to the visible surface of the sun, called the photosphere. They captured waves of giant plasma blobs, which drew their energy from magnetic fields, falling from the corona onto the photosphere.

“We saw ribbon-like features moving extremely quickly through the sun’s atmosphere, even before the main flare episode,” Chitta said. “These streams of rainy plasma drops are signatures of energy deposition, which become stronger and stronger as the eruption progresses. Even after the eruption has subsided, the rain continues for some time.”

After the flare reached its peak energy, during which X-ray levels increased dramatically and charged particles were accelerated to between 40 and 50 percent of peak energy. speed of lightthe cross-shaped magnetic region began to relax. The plasma cooled and particle emission decreased to normal levels. Chitta described how it was completely unexpected that the avalanche process could result in such high-energy particles.

The avalanche model of weaker disturbances turning into something more severe had previously been proposed to explain the collective behavior of hundreds of thousands of flares across the sun, but until now it hadn’t really been considered that it could apply to a single flare.

Two important questions arise from this. First, are all solar flares produced as an avalanche? “What we observed challenges existing theories about energy release through flare,” said David Pontin of the University of Newcastle, Australia, who was part of the team analyzing the Solar Orbiter data.

Further observations of solar flares will be necessary to shed light on this point.

Second, our Sun isn’t the only star to get flares. They spring from all stars and certain stellar bodies, such as red dwarfshave much more powerful and frequent flares than the sun.

“An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism occurs in all flares and on other blazing stars,” Janvier said.

The results of Solar Orbiter observations of the September 30, 2024 eruption were published on January 21 in the journal Astronomy and astrophysics.