Billie Eilish, stolen land, and the climate cost of America’s dispossession

When Billie Eilish told the Grammys audience that “no one is illegal on stolen land,” she ignited a small firestorm that overtook celebrity speech, revealing deep fractures in how America confronts its own history.

Critics have accused her of hypocrisy, pointing out that her multimillion-dollar Los Angeles home sits on Tongva land. Republican Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas invoked his position during a Senate hearing, calling the entertainment world “deeply corrupt.” Meanwhile, pundits and commentators have spawned backlash and memes online. And the Washington Post published an opinion piece defending the property law and rejecting land restitution.

“No, Billie Eilish, Americans are not thieves on stolen land,” article authors Richard Epstein and Max Raskin wrote Thursday. Days before, Eilish responded to the ongoing Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids and killings by highlighting America’s history of violent colonialism and genocide directed against indigenous people. The Washington Post’s writers argue that “it’s time to put Eilish’s theory of ownership out to pasture,” arguing that “it’s easy to dismiss as stolen land, but what about the innocent buyers who acquired in good faith in the meantime?” Are they thieves?

This language, these arguments are reasonably predictable. They appear when indigenous dispossession is brought into the public eye.

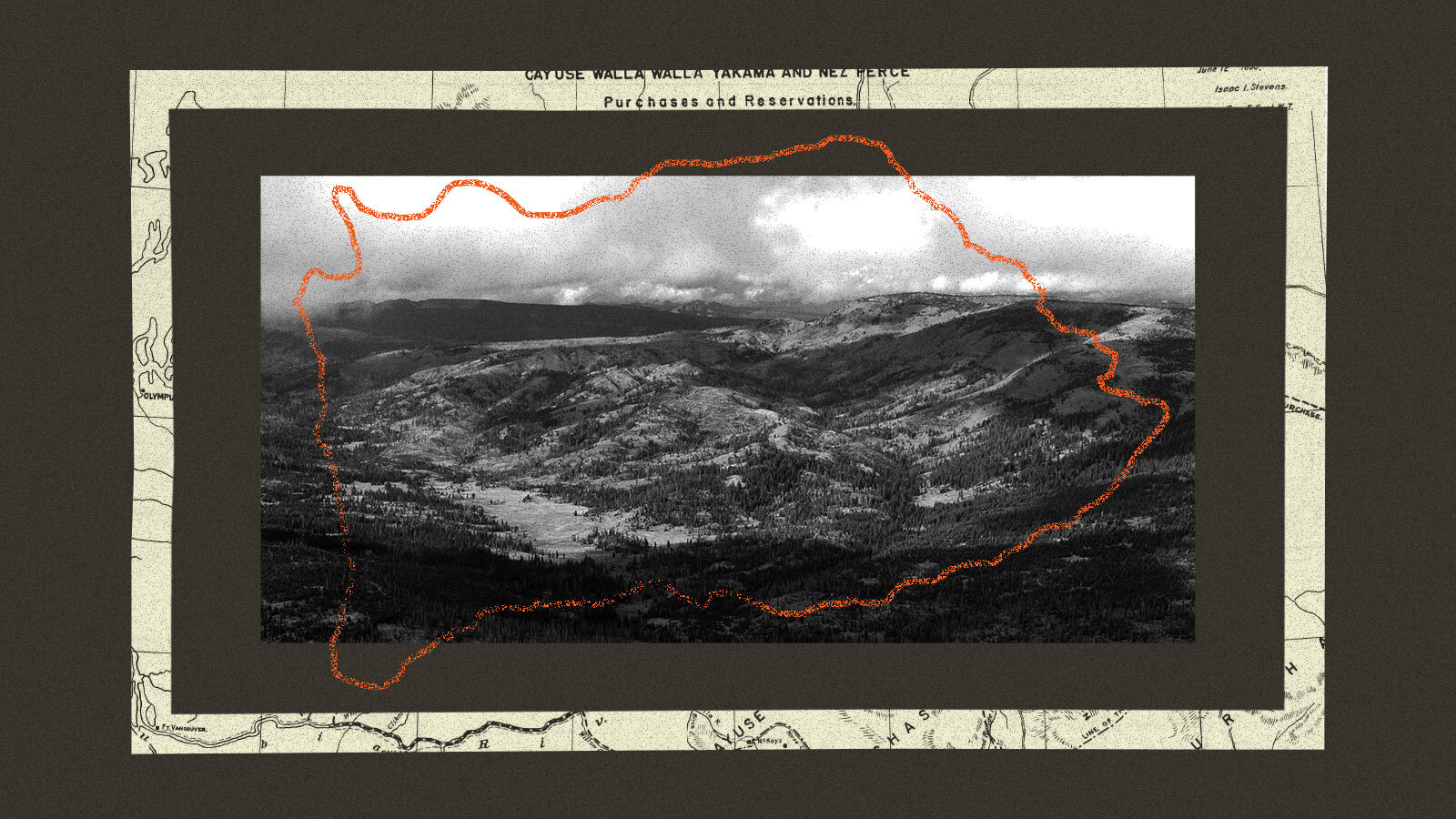

But there are countless examples throughout history of indigenous peoples being forced to give up their land under threat of violence, such as in what is now Washington state. Between 1854 and 1855, Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens pressured the region’s tribes to cede a large portion of the West Coast to the United States. His warning to Chief Yakama Kamiakin was explicit: “if you do not accept the offer…you will walk knee-deep in blood.” The threat was not rhetorical: Less than a decade earlier, the California Gold Rush had brought settlers west and resulted in what California Governor Gavin Newsom would later call genocide. “There’s no other way to describe it,” Newsom said in 2019. “That’s how it should be described in the history books.”

The United States frequently combined economic pressure, unequal bargaining power, and the threat of military force in treaty negotiations, and the creation of Minnesota was no exception. The federal government withheld rations promised to tribes after previous land cessions and allowed settlers to violate prior treaties – which constitute federal law – in order to hunt and claim land within the agreed-upon Indian Territory. With the treaties of 1851, signed at Mendota and Traverse des Sioux, the Dakota Nation was forced to cede 35 million acres, almost the entire lower half of what would later become Minnesota. Tensions eventually led to the Dakota War, a five-week conflict that forced the expulsion of nearly all of the state’s indigenous people. These actions, this war, have also been called genocide by Holocaust and genocide scholars, as well as the direct beneficiaries of the law: the city councils of Minneapolis and St. Paul.

Rick Bowmer / AP Photo

Writing in the Washington Post, Epstein and Raskin refer to the land acknowledgments that arise from these stories as “an acceptance of generational guilt,” adding that apologetic statements, like those from the state of California, “fortunately” do not transfer title to the original owners, “because if they did, civilization would collapse.”

Scholars of settler colonialism have long documented how the United States presented whiteness as synonymous with “civilization,” while presenting indigenous peoples as obstacles to progress—a racist framework in which property becomes the key marker of civilization. Epstein and Raskin’s argument clearly fits into this tradition. By treating land titles as the foundation of civilization, it obscures the history that made them possible: war, forced displacement, forced assimilation of children, and policies that historians and government officials have called genocide.

Consider the Morrill Act of 1862, which used land confiscated from tribal nations to fund the land-grant university system: nearly 11 million acres confiscated from more than 250 tribes to create 52 universities.

Extractive industries fill the coffers of public universities on stolen land

Then there are the state enabling acts, laws passed by Congress that authorize the formation of a state government and authorize admission to the Union. As indigenous lands became territories and territories became states, newly formed state governments extracted land from their newly acquired “public domain” through their enabling laws to fund state institutions, services, and public works. These lands are now known as state trust lands.

The primary purpose of state trust lands was education and remains so to this day. Land-grant colleges, for example, opened with help from the Morrill Act, and then states stepped in with more revenue from state-grant lands. Careful investigations have since identified 14 land-grant universities still benefiting from more than 8 million acres of land taken from 123 Native nations through 150 Native land cessions. These lands generated approximately $6.6 billion in profits between 2018 and 2022.

Nearly 25 percent of state-trusted land that benefits land universities is earmarked for mining or fossil fuel production. In Montana, oil and gas extraction, logging, grazing and other activities on state-owned lands generated $62 million for public institutions, with the majority of that money going to elementary and secondary schools. Ten states use nearly 2 million acres of state trust land to fund their prison systems. In 2024, these lands provided an estimated $33 million in funding to prison facilities. At least 79 reservations in 15 states have state trust lands, an estimated 2 million acres, within their borders that generate revenue to support public institutions and reduce the financial burden on taxpayers. “Every dollar the Land Office makes,” New Mexico Public Lands Commissioner Stephanie Garcia Richard said in 2019, “is a dollar taxpayers don’t have to pay to support public institutions.”

In at least four states, tribal nations pay states to access these lands, even though they are within their own territorial boundaries – about 11,000 acres. The Ute Tribe paid the state of Utah more than $25,000 to graze on these trust lands in 2023 alone. Although critics have been quick to point out that institutions such as elementary and secondary schools benefit everyone, it is important to remember that many tribal members do not attend public schools at all, but enroll in Bureau of Indian Education schools that receive funding from the federal government.

But the restitution of these lands remains mired in bureaucracy. In 2024, Grist reported that more than 90,000 state trust lands inside the Yakama Reservation – the reservation created under the threat of walking knee-deep in blood – had been mistakenly carved out of the Yakama Nation due to a federal filing error. The tribe has fought for nearly seven decades to have their land returned, but Washington has refused to let them go: U.S. property law dictates that state ownership of such land is legal because the state holds title to the land.

A filing error put more than 90,000 acres of Yakama Nation land in the hands of Washington state.

But Washington recognizes that this is an injustice and that these lands should be returned to the tribe. However, then-Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz argued that righting this wrong would take away revenue from beneficiaries like elementary and secondary schools. The state should therefore be compensated for its loss of revenue, even if these lands were illegally seized in the first place. Between 2021 and 2023, these state trust lands generated approximately $573,000 for state beneficiaries, or less than 1% of all revenue from all trust lands in Washington state.

In the Washington Post editorial, the authors assert that “the effort to undo the past would involve trillions of dollars in wire payments and forced title transfers that would upend every home mortgage, every mining and oil lease.” They are right. Returning land to tribal nations would undermine – pun intended – the very foundations that are driving climate change and threatening life on the planet. A fact echoed by more than 600 scientific and conservation studies over the past 20 years, according to which the restitution of indigenous lands offers significant environmental benefits with serious implications for the fight against climate change.

Ultimately, the controversy surrounding Eilish’s remark reveals less about celebrity or even ownership than the limits of the American moral imagination, including in influential media. Democracy may die in darkness, but America was built in broad daylight, and in America, oppression and injustice do not need shadows to thrive: they need champions.