Scientists discover strange hidden structures in DNA

Scientists have noted that the torsion structures in DNA are long with the nodes are in fact something else.

Inside cells, DNA Is twisted, copied and separated. The twists and turns can influence the functioning of the genes, affecting that are activated and when. The study of how DNA reacts to stress can help scientists better understand how genes are controlled, how the molecule is organized and how the problems with these processes can contribute to the disease.

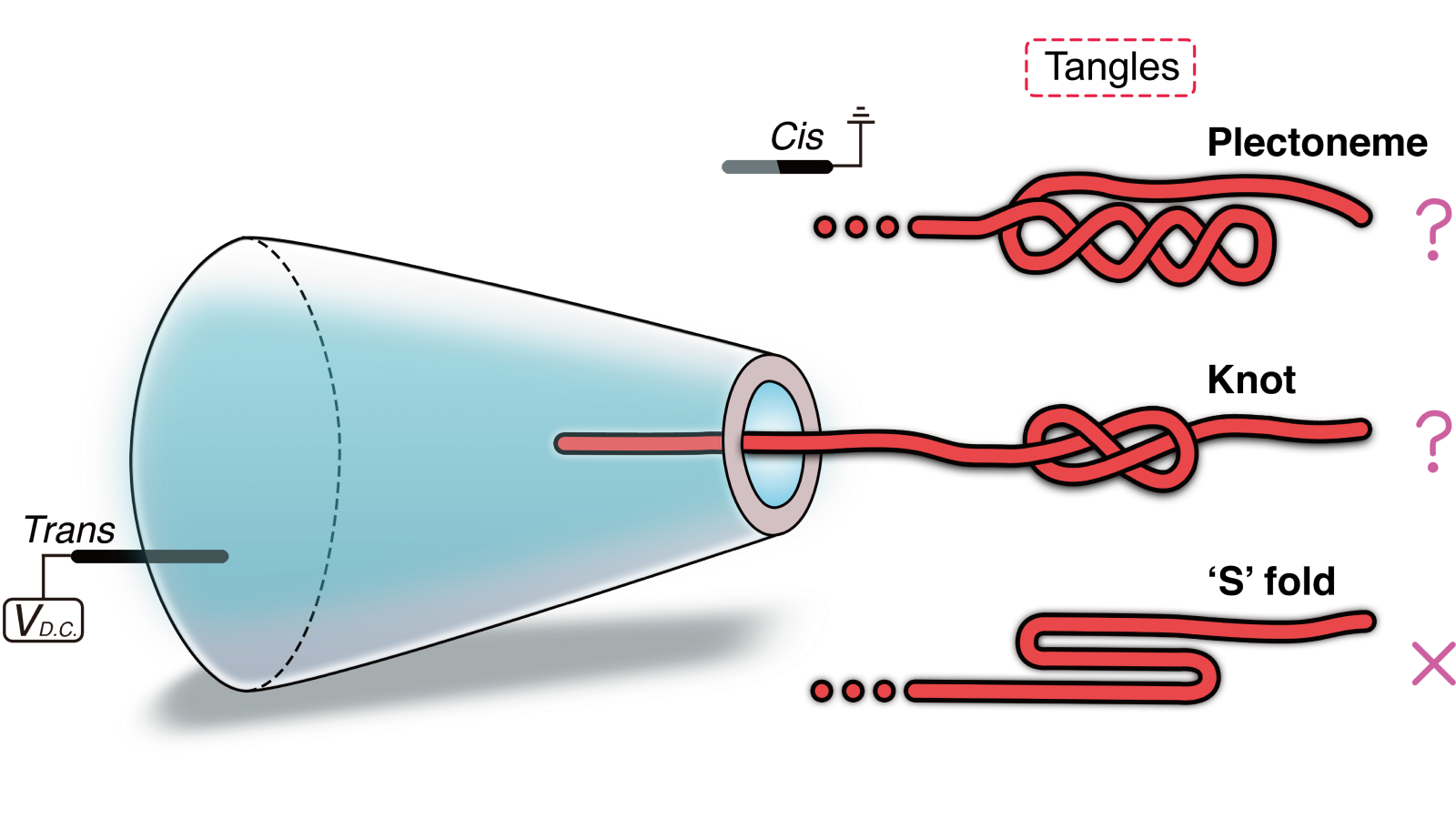

For years, researchers have used nanopores – tiny holes just wide enough for a single bit of DNA pass through – to read DNA sequences quickly and at low cost. These systems work by measuring the electric current crossing the nanopore. When a DNA molecule passes, it disturbs this current in a distinct manner which corresponds to each of the four “letters” which make up the DNA code: A, T, C and G.

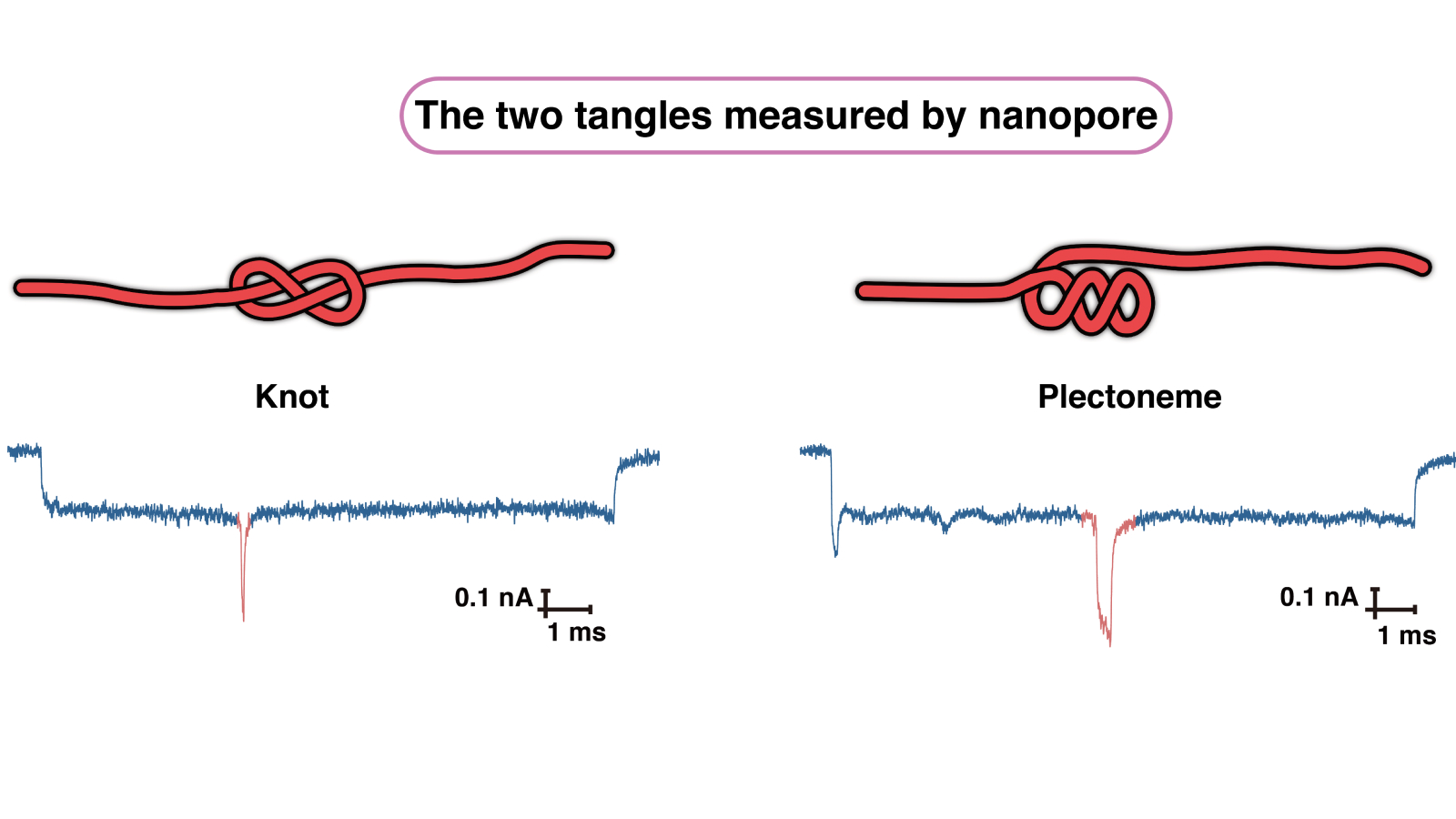

Slowdowns or unexpected points in this signal have often been interpreted as nodes in DNA. But now, a new study published on August 12 in the journal Physical review X Notes that these signal changes can also mean plmesme plmesmes, which are natural coils that are formed when DNA twists up under stress.

“Nodes and PlectONES can be very similar in nanopore signals”, main study author Ulrich KeyserA physicist for the Cavendish laboratory at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science. “But they come from very different physical mechanisms. The nodes are like tight tangles; the potth is more like rolled up springs, formed by a couple.”

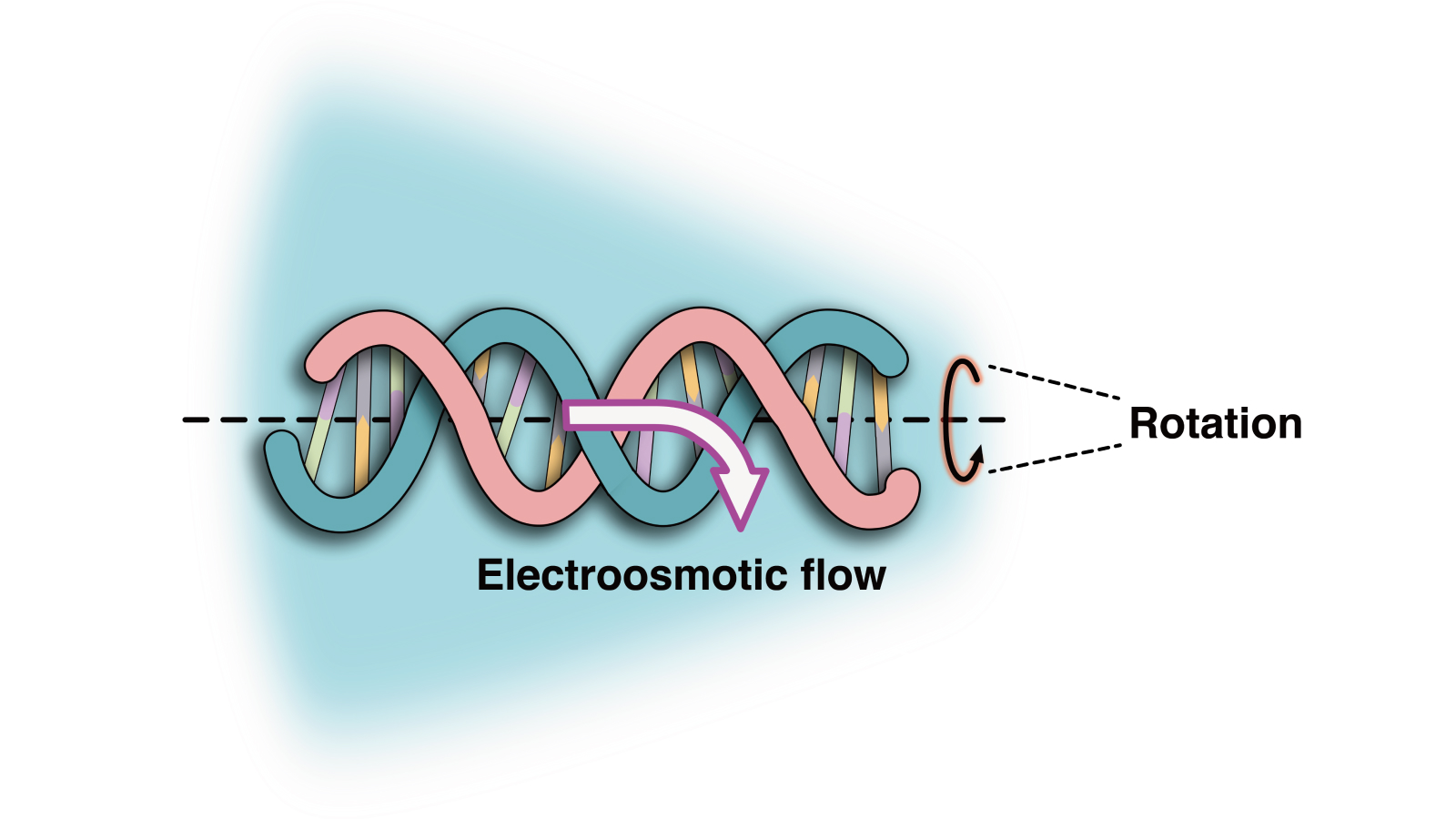

To study these coils, the researchers had a touch of DNA through a cone -shaped nanopore in a salty solution with a high pH. The solution has contributed to creating an electroosmotic flow, which means that DNA began to turn by entering the pore. The movement generated a sufficiently strong, or couple torsion force, which he wrapped DNA, explained Keyser.

In relation: DNA has an expiration date. But proteins reveal secrets about our ancient ancestors that we never believed possible.

Keyser and his team also applied electrical voltage through the nanopore to help browse DNA and measure electric current changes.

“In this kind of nanometric scale systems, everything is very high, so DNA moves almost as if it swims through honey,” said Keyser. “It is a very viscous environment, so relatively high forces push DNA in this corkscrew movement.”

The researchers analyzed thousands of these events. While some nodes have always appeared in the experience, they tended to be smaller – about 140 nanometers in diameter – while the Plectonths had about 2,100 nanometers in diameter. As the voltage applied to the system increased, the properly became more common due to a stronger torque.

To test more how the torsion affects DNA behavior, the researchers introduced small ruptures, called Nicks, in a bit of DNA double propeller. These Nicks allowed DNA to turn more easily and to release the accumulated tension, which, in turn, caused a formation of proper. This confirmed that the torsion stress is a key engine for the formation of these structures.

“When we have checked the ability of the molecule to turn, we could change the frequency to which the PlectONES appeared,” said Keyser.

Although nanopores are very different from living cells, these types of potential can also be formed during processes such as transcription and replication of DNA. The transcription describes when the DNA code is copied by another molecule, called RNAand shipped in the cell. The replication describes when the DNA molecule is reproduced in whole, which occurs when a cell is divided, for example.

“I believe that torsion in molecules can actually give birth to the formation of ITS I and G-QuadruplexKeyser told Live Science, giving the names of two specific types of nodes seen in DNA. So what they found in their laboratory study probably has implications for living cells, he explained.

Keyser and his team have studied how the Plectonths and other DNA structures are formed during natural processes, such as transcription. In previous workThey explored how to twist stress affects DNA replication. Nanopores give scientists a way not only to read DNA but also to see how it behaves, this study emphasizes.

“The mere fact that the DNA molecule can sneak through the pore, where its rigidity is supposed to be much greater than the diameter of the pores, is quite incredible,” Slavic GarajA physicist at the National University of Singapore who was not part of the study, told Live Science. “It is 10, 50, even 100 times more rigid than the size of the pores. However, it folds and passes.”

Garaj was enthusiastic about the results. In the future, “we could be able to separate the torsion induced by the torsion nanopore which was already in DNA before. This could let us explore the natural super-coil of new ways,” he added. This would be important to understand how coils and nodes control the activity of genes.