‘Perfectly preserved’ Neanderthal skull bones suggest their noses didn’t evolve to warm air

A digital analysis of the perfectly preserved nose bones on a bizarre object Neanderthal The skull reveals that a long-held theory about Neanderthal noses doesn’t pass the sniff test.

The skull comes from “Altamura Man,” one of the most complete and best preserved Neanderthal skeletons ever discovered. Speleologists discovered it in 1993 while exploring a cave near the town of Altamura in southern Italy. Because it is covered in a thick layer of calcite, or “cave popcorn,” Altamura Man was not removed from the cave, to avoid damaging the bones. This Neanderthal probably died at the exact location where the skeleton was discovered, between 130,000 and 172,000 years ago.

“The general shape of the nasal cavity and nasal opening in Neanderthals follows a fairly consistent trend,” lead author of the study Costantino Buzipaleoanthropologist at the University of Perugia, told Live Science in an email. “Typically it starts out large but gets larger as it evolves, with very large nasal openings in later populations of the species.”

One theory regarding Neanderthals’ large noses is that they had sinuses just as big and a improved airways which evolved as adaptations to life in cold, dry environments. Their particular nasal anatomy could have been useful for warm and humidify the air before it reaches their lungs. But all previous studies of Neanderthal nasal anatomy were based on approximations delicate bones of the nasal cavity, since these bones—the ethmoid, vomer, and lower nasal conchae—were broken or missing in every Neanderthal skull ever discovered.

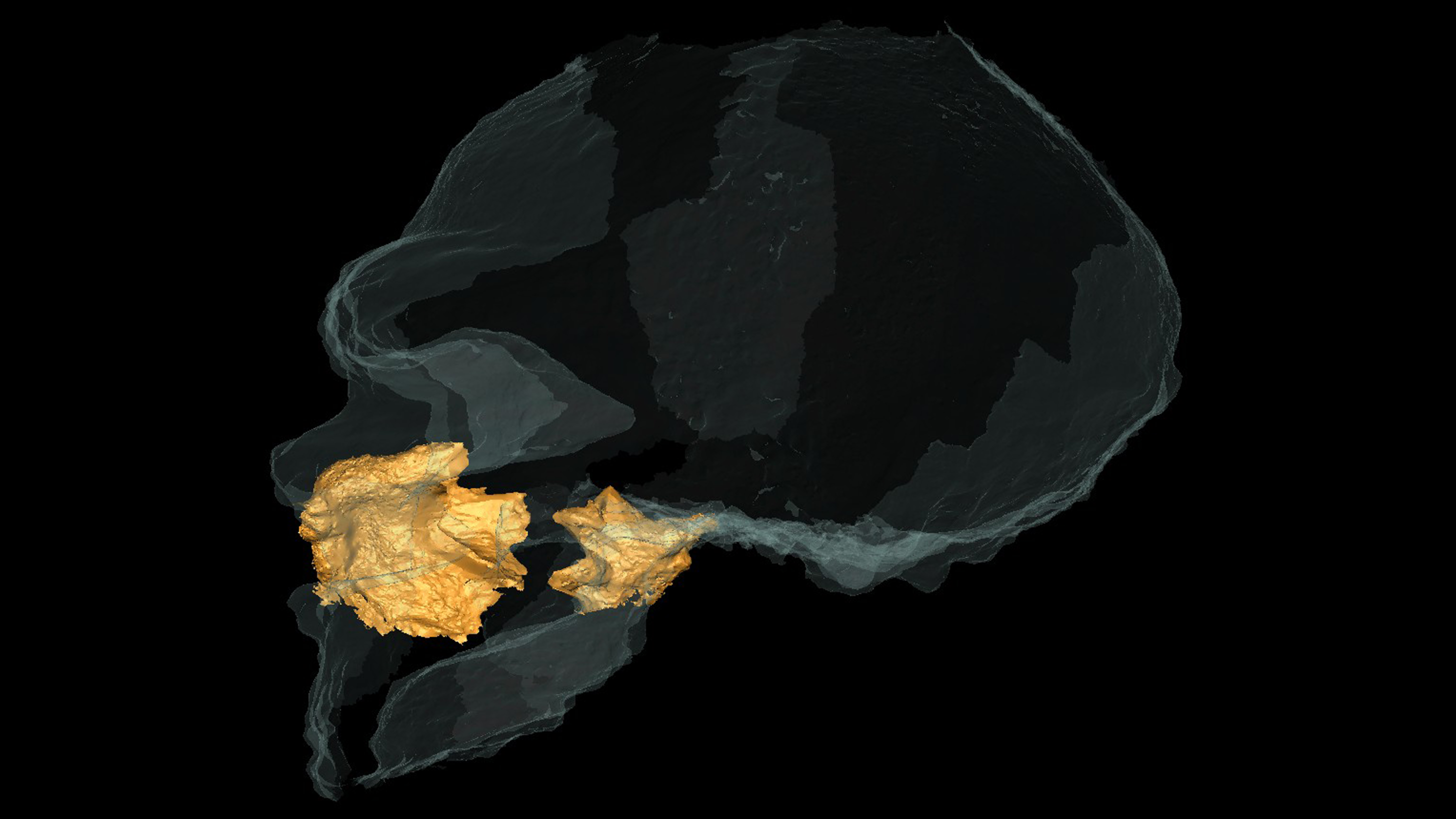

Buzi and his colleagues worked on a “virtual paleoanthropology” project to document and digitize Altamura Man without removing the specimen from the cave. Using endoscopic probes, the researchers acquired video of the interior of the skull’s nasal cavity and created 3D photogrammetric models of the Neanderthal nose bones for the first time.

When the researchers analyzed the endoscopic images, they found that the Altamura man’s internal nasal structures were neither unique nor substantially different from those of modern humans. Although the rest of the Neanderthal skeleton appears adapted to the cold – with shorter limbs and stockier build than those of modern humans – his nose was not.

The new study is informative, Todd Raea paleoanthropologist at the University of Sussex who was not involved in the work, told Live Science in an email, “in that two of the three previously proposed unique features of the Neanderthal nasal cavity do not appear to be present in this specimen.” The lack of unique traits, Rae said, “shows that there is variation in species that was not previously known.”

Buzi acknowledges that Neanderthals likely exhibited some degree of intraspecific variability, but he cautions that strong evidence for this variation is limited, since only Altamura has provided evidence for the internal structures of the Neanderthal nose.

But the reason Neanderthal noses were big may have nothing to do with biological adaptations to the cold, Rae said.

“All previous species of Homo to have wide noses“, said Rae, and “most Homo sapiens have broad noses – only the people of Northern Europe and the Arctic do not, a tiny proportion of the species.

Rather than viewing the Neanderthal nose as a unique adaptation to the cold, it is better understood as an efficient means of altering the temperature and humidity of inhaled air necessary for Neanderthals’ massive bodies to function. Many environmental pressures and physical constraints probably helped shape the Neanderthal face, Buzi said, “resulting in an alternative model to ours, but perfectly functional for the harsh climate of the European Late Pleistocene.”