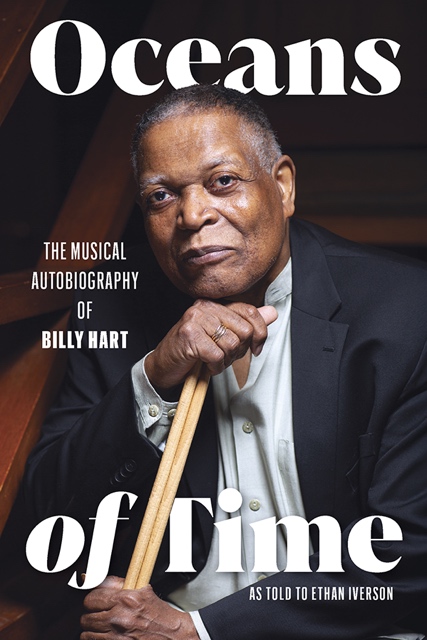

Billy Hart’s Life in Rhythm

The legendary jazz drummer played with Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, and Stan Getz. His new memoir tells all—and lays out his own philosophy.

Billy Hart in concert at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola in May 2017, with his distinctive cymbal setup.

(Alan Nahigian)

The first time someone asked me to define swing, it was a Japanese interviewer in Nagoya. I was dumbfounded—how do you explain it? Can you explain a religion in a word or two? A person of African descent would never have asked that question, especially if they had grown up in the Black American church. Finally, I said, “‘Swing’ is a musical system that causes joy, euphoria, and optimism.”

When I was a high school student in Washington, DC, I only got 35 cents a day for lunch money. If I saved up all week, it was just enough to go to see the great singer and pianist Shirley Horn play at the Brass Rail on the weekend. Her drummer was the top drummer in town, Harry “Stump” Saunders, who also played a lot with the local saxophone legend Buck Hill. Stump was tight with Jimmy Cobb, and they had a similar approach, with this serious Washington, DC, beat. Wow, this cat could play! Stump had a head on his bass drum that wasn’t just cowhide, it still had the cow hair on it. When he hit that bass drum it was like somebody punched you in the chest. Man, you can’t imagine that groove. The groove was so deep and they were swinging so hard and Shirley was singing. Wow!

Listening to Shirley Horn and Stump Saunders certainly taught me something about euphoria. Stump was in the line of Kenny Clarke, Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, Louis Hayes, Art Taylor, and the other magnificent midcentury masters of American classical music. I still try to play like Stump to this day.

There’s not a lot to write about whatever “swing” is that looks absolutely correct. Those with African heritage value the oral tradition over the printed page. Still, there are a few things one can explain about the four limbs at the drums in the matter of a Stump Saunders.

The meter is in 4/4. Not too long ago I worked with Archie Shepp in Paris. John Coltrane was like an uncle to Archie, so I asked Archie if he had talked to John about odd meters like 5/4 and 7/4. According to Archie, Coltrane said, “You know, I’ve tried everything, but nothing swings as hard as 4/4.”

“Swing” also means that the beat fluctuates a bit. You need accurate time, of course, but if you play as accurately as a metronome that ends up sounding stiff.

Current Issue

On the ride cymbal, the right hand plays a blues shuffle with a couple of the middle notes left out: “spang, spang-a lang, spang-a-lang.” Apparently, that beat is the invention of Kenny Clarke. A great drummer can play the hell out of that cymbal beat—I modeled my own ride cymbal style on Max Roach and Art Blakey. But the cymbal is not quite enough on its own to generate euphoria; it needs to be related to the other limbs.

The wonderful drummer Eddie Moore started his students not with straight 4/4 but with what is sometimes called “The Universal Rhythm,” a basic syncopation heard in almost all the cultures of the world. In Brazil it is in the baião; in Cuba, the tumbao; it’s in Indian and Japanese music; the second-line; James P. Johnson’s “The Charleston;” and so many other places. Of course, the true antecedent is Africa. You can notate this rhythm as 3-3-2, or as dotted quarter note, dotted quarter note, and quarter note.

In jazz drumming, the left hand can play fragments of the Universal Rhythm as well as other kinds of commentary. I sometimes think that the most swinging left-hand accent is the “and” of beat three. Billy Higgins could really play that accent with drama.

When discussing the rhythmic properties of jazz, I’m afraid my young DC jazz crowd regularly made fun of white people as the stiffest and most un-swinging people around. Yeah. We’d do high comedy, always with the implication that the Caucasian community had no idea what the emotion of “swinging” was, unless they got ahold of the wrong end of that basic idea and displayed it in an over-dramatic fashion. There was nothing better than joking about European people clapping on beats one and three for a polka or a hoedown. The way a jazz drummer plays beats two and four on the hi-hat emulates an Afro-American dance party, where people are clapping their hands. Whatever we did, we made sure not to do it “white.”

The right foot on the bass drum keeps the 4/4 going with “feathering,” a soft hum of quarter notes. The early New Orleans music swung hard, no doubt, but the music settled into an even deeper groove in Kansas City and the Southwest a decade or two later—they called some of the important groups from that era “Territory Bands.” It’s possible that feathering the bass drum comes directly from the low tom-toms of the Native Americans. You can’t hear the feathering on the records as clearly as the other limbs, someone has to show you how to do it. Buck Hill was the first person to tell me about feathering.

Occasionally, I describe jazz as “America’s classical music,” and one person who taught me that was Buck Hill. Buck played so good, everything was correct, and everything around him on the bandstand also had to be correct.

All cultures start with music for dance, ceremony, and communication, and develop folkways and mores concerning this local music. But after mastering those folkways and mores, some musicians are curious about other possibilities and seek to combine their indigenous culture with sounds from other places. The United States is the one country that had all these cultures rubbing right up next to each other. You don’t even need to go around the block to find something different, it’s right across the street.

As the music evolves, it transitions from folk music for dancing to classical music for listening. When we say “classical music” we often think of Europe. But within Europe, all the classical music is different: the French, the English, the German, the Italian, the Spanish. The Russians are a whole ’nother thing. They all have a different nationalistic folk base. Unlike all those European classical musics, in America, our classical music was deeply informed by the classical musics of India, South America, and especially Africa.

Human nature is the same anywhere. We all get happy or sad, we all violate the Ten Commandments in our own little ways. Folk music reflects this basic human understanding. It’s important for me to keep a folk perspective in my own approach. I’ve noticed that those who go strictly in an academic direction start criticizing all sorts of music. If you can stay connected to folk music, you have more love for variety. Apparently, both Charlie Parker and John Coltrane never had a bad word for any serious musician.

Nobody played more complex music than John Coltrane, but he always had that folk perspective in play. Black gospel is one of our American folk musics, absolutely crucial to American classical music, and Coltrane always remained a church musician, no matter the intellectual density of his sound.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Any classical music has its rules and regulations too, of course. Some people think “jazz means, “play whatever you want,” but that is simply not the truth.

Dave Liebman says I am a devil’s advocate—that whenever someone offers a strong opinion, I say the opposite. Dave has yelled at me more than once: “Jabali! Take a stand! Right or wrong, take a stand!”

Buster Williams has said something similar. After I won the NEA Jazz Master award in 2021, Buster called me and said, “Well, enough of this bullshit act you’ve been pulling for all these years. I hope you’re finally ready to tell it like it is.”

I tried to gain time by telling him, “But, man, Buster, you should have gotten the award, not me!”

“That’s exactly what I’m talking about!” Buster countered. “No more of that bullshit!”

My short acceptance speech at the NEA awards included one equivocal word:

John Coltrane said that he wanted his music to be a force for good. Coltrane’s comment has inspired my own path of purpose. This path started many years ago in Washington, D.C., before sending me on to play with so many friends, heroes, mentors, and students. Getting this recognition tonight from my government apparently validates this path—this path of purpose. Thanks to the National Endowment of the Arts, SFJazz, and everyone else who has helped me all these years. I am happy to have walked this path!

The equivocal word, of course, was “apparently,” and it got a big laugh.

More from The Nation

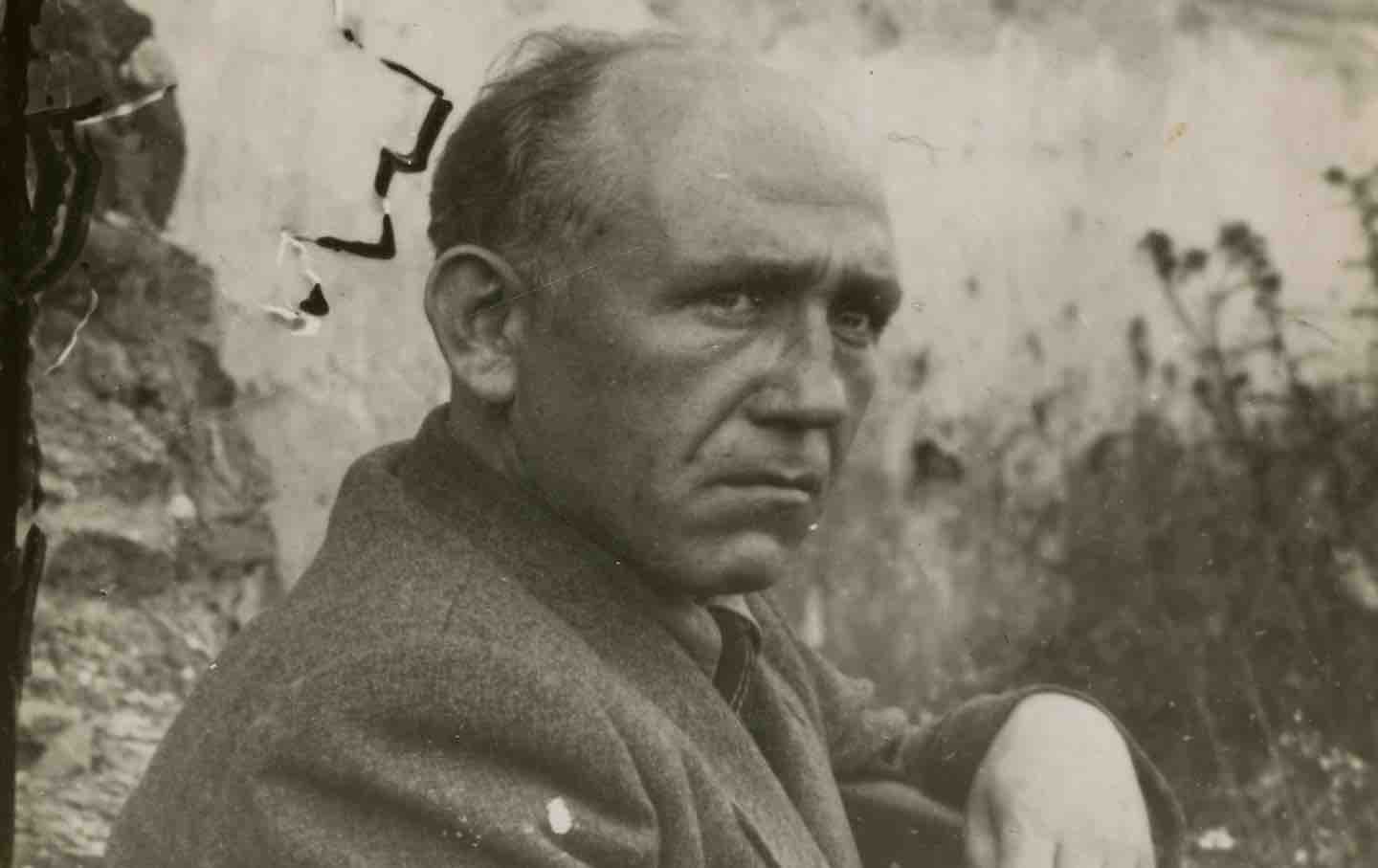

The Yiddish writer’s lost masterpiece, Sons and Daughters, brought back to life, in all its humor and beauty, the Jewish shtetl of his youth.

Lily Meyer

In The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, the journalist broke free of his contrarian clichés to illuminate the origins of 1960s counterculture.

Nick Burns

A new play about Roald Dahl shows the now-controversial children’s writer in his flawed, complicated reality.

Katha Pollitt

Nathan Kernan’s biography of the New York School poet tracks the development of his serene and joyful work alongside the chaos of his life.

Books & the Arts

/

Evan Kindley

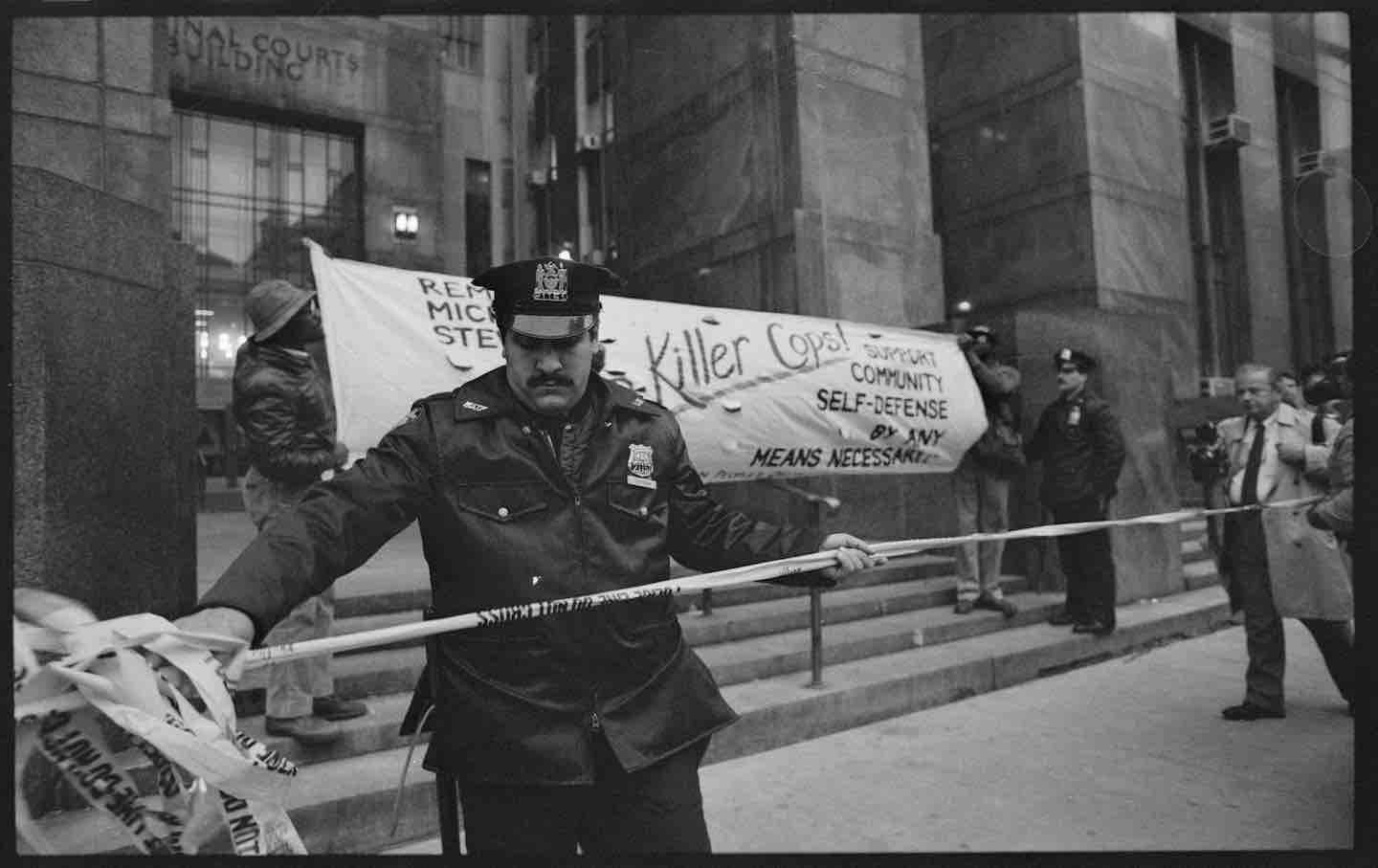

In 1985, police were acquitted in the killing of a graffiti artist and painter, a grisly act that galvanized the city’s art underground. Why has he been forgotten?

Books & the Arts

/

Michael Shorris