Cop30 live: first draft text revives shift away from fossil fuels | Climate crisis

First draft text revives shift away from fossil fuels

Fiona Harvey

When is a cover text not a cover text? When it’s a mutirão decision! The first draft of a potential outcome from the Cop30 has landed, put up on the UN web site on Tuesday morning, and it’s fascinating.

This will not be the only text from Cop30 – there are also texts on all of the other decisions that will be made at this Cop, in various stages of draft or not draft yet – but the mutirão decision takes in the “big four” issues that were too difficult to be included in the official agenda.

It also – surprisingly – includes lines referring to the “transition away from fossil fuels” among the options for an outcome. Discussion of this issue – which was agreed as the key resolution from Cop28 in 2023 – was effectively shut down last year in Baku, and in Belem has taken place only on the sidelines up to now.

The draft text is an elaboration of the “note” sent by Brazilian Cop president Andre Correa do Lago on Sunday night, formalised into the shape of something that could be gavelled through as a decision. In a letter on Monday night, do Lago suggested that the gavelling could be done after a meeting of ministers on Wednesday.

That would be astonishingly fast, and is frankly not likely. The discussions on the big four issues – finance; transparency; trade; and a response to the fact that current national climate plans (NDCs) are too weak to keep the 1.5C heating limit – have been going on since before the start of this conference last Monday, and the text shows – in its many options – that nations are still far from resolving them.

The draft mutirão text includes text that would allow for an annual review of countries’ NDCs, with a view to strengthening them to meet the 1.5C (2.7F) goal. That sounds a bit like the idea agreed at Glasgow’s Cop26 in 2021, for a faster “ratchet” to the Paris agreement – in the agreement, countries must return every five years with strengthened NDCs; at Glasgow, countries were invited to ratchet up their targets on a more frequent basis, but this was voluntary, and almost no countries availed themselves of the opportunity.

Countries are also invited – and here is a nod to China, which it is frequently noted tends to under-promise on its emissions targets and then over-deliver – to “aim to overachieve NDC targets”. China has been adamant at this Cop that there should not be a discussion of NDCs. Under the letter of the Paris agreement, such a review only needs to take place in three years’ time, under the second “global stocktake” – a mechanism for the assessment of NDCs every five years. But campaigners and many countries believe that waiting three years to be told that the NDCs are inadequate would waste yet more valuable time, and effectively nail shut the coffin of the 1.5C target.

Another option in the mutirão text is for a “Global Implementation Accelerator”, a new idea which would also be voluntary, and would “accelerate implementation, enhance international cooperation, and support countries in implementing their nationally determined contributions [NDCs]”. A third option is for a “Belem Roadmap to 1.5” which would set out what needs to be done to put the world on track to meet the Paris goals.

Mention of the “transition away from fossil fuels” falls under two options in the text, one the above first option of a response to the inadequacy of the NDCs, where it is accompanied by the other resolutions made at Cop28 of tripling global renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency by 2030, and the other an option for a “high-level ministerial round table on different national circumstances, pathways and approaches with a view to supporting countries to developed just, orderly and equitable transition roadmaps, including to progressively overcome their dependency on fossil fuels and towards halting and reversing deforestation”.

Finance is mentioned 26 times in the text, reflecting its centrality to all developing countries meeting in Belem. Developed countries are urged to set out their plans to provide financial assistance more clearly, in some of the five options on finance that are listed, including a ministerial round table on delivering the $1.3 trillion a year in climate finance promised to poor countries at last year’s Cop in Baku. Another is for a “Belem Global De-Risking and Project Preparation and Development Facility (“Belem Facility for Implementation”) to catalyze climate finance and implementation in developing country Parties by translating nationally determined contributions and national adaptation plans into project pipelines”.

That a text has been produced in which the transition away from fossil fuels makes it this far is itself a minor miracle. This could yet be watered down or rejected. But it is now looking likelier that some form of response to the 1.5C target and the NDCs – which could involve a strong financial element, as developing countries rightly insist that they cannot meet targets without more financial assistance than has yet been forthcoming – could be included in the Cop30 outcome.

Key events

Dharna Noor

Take a minute to wrap your head around the latest piece of climate summit jargon. My colleague Dharna Noor has written a helpful explainer on Bam, a proposal for states to drive action on a just transition towards a low-carbon economy. A few key points follow below.

What is a just transition?

The concept of the just transition originated from the US labour movement, specifically from energy and chemical workers who said employees of polluting sectors should be supported and compensated as they move into more environmentally friendly jobs.

It has since been taken up by civil society organisations and expanded to include all people affected by sectors that are shifting as climate policies are enacted. That includes workers in the booming transition minerals sector, as well as people living near mineral extraction sites. It also encompasses people affected by attempts to clean up the agriculture sector.

When did the just transition become a consideration in Cop negotiations?

The preamble to the 2015 Paris agreement mentioned the framework, when parties agreed to “taking into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities”. It acknowledged that without planning, the shift to a low-carbon economy could leave workers and communities behind. But preamble text does not lead to implementation.

During the 2018 climate talks in Katowice, the just transition concept entered the sphere of negotiations when a committee of experts convened by Cop officials considered it. Three years later, at Cop27 in Egypt, parties created the “just transition work programme”, which was intended to help countries design fair pathways and mitigate unintended harms of climate action.

The following year in Dubai, officials fleshed out the programme some more, including by agreeing to hold regular dialogues for parties focused on the just transition. But none of those agreements included requirements for parties. Bam supporters say they have a plan to fix that.

What would the Bam do?

Bam proponents say a new mechanism is needed to require countries to take concrete steps toward a just transition. Right now, global just transition efforts are fragmented and inconsistent.

“No one is even tracking progress on this,” said Teresa Anderson, the global climate justice lead at the NGO ActionAid. “Bam would fix that.”

Bam would also require countries to coordinate their work supporting a just transition, ensuring everyone knows what is happening globally and who it is affecting. It also aims to develop ways for countries to share best practices on a just transition and to support the implementation of such policies, especially in low-income countries with limited state capacity.

And though it would not mandate any new spending on climate finance, it would prioritise non-debt-inducing finance and ensure technology is shared with developing countries – values that states agreed to uphold in the Paris agreement.

Nina Lakhani

The Guardian environment team is not known for its good news content, but a crucial vote in Ecuador on Sunday delivered a win for the climate, biodiversity and democracy.

Ecuadorians overwhelmingly voted down four proposals that included rewriting the constitution that recognises the rights of nature – a unique protection that has empowered Indigenous peoples and other civil society groups to defend the Amazon, Galapagos islands, Andean highlands, and other vital ecosystems. Ecuador, which straddles the equator, is among the most biodiverse places on the planet, with the Amazon rainforest covering almost half of the country’s land area.

President Daniel Noboa, the 37-year-old right wing leader, banana magnate and close ally of Donald Trump, has proposed a $47bn oil expansion plan in the Amazon and building housing and hotel complexes on the Galápagos Islands, a Unesco world heritage site and biosphere reserve. Sunday’s vote was a clear rebuke of Naboa’s authoritarian tilt, with voters also rejecting the return of foreign military bases to the country, and against proposals to curtail party funding and reduce the number of parliamentarians.

Voting in Ecuador is compulsory. Over 80% of eligible voters took part in the referendum, according to the National Electoral Council (CNE).

In the run up to Sunday’s vote, Indigenous and environmental leaders told the Guardian that they were facing a wave of state intimidation tactics including having bank accounts frozen. In September, an Indigenous land defender, Efraín Fueres, was shot and killed by the army during a protest against the high cost of living, a lack of medicine in hospitals, the deterioration of schools and growing social insecurity.

Ed Miliband: forces of denial and delay are ‘losing this fight’

We should not fear the forces of denial and delay, UK Energy Secretary Ed Miliband has warned, because “they are losing this fight”.

Speaking to delegates at Cop30, the Labour politician acknowledged the existence of climate deniers and delayers across the world – including in the UK – and described them as “well funded, well organised, and determined”.

But he also said those forces were losing the fight.

He said: “They are losing because of economics: We are now seeing the world invest twice as much in clean energy as fossil fuels. They are losing because countries are acting: We see 80% of the world’s GDP covered by net zero commitments, and in the years since the Paris agreement we have seen forecast warming cut from 4C to around 2.3-2.5C.”

The UK is one of the world’s greatest historical polluters of planet-heating gas, having kicked off the Industrial Revolution. But it has also cut emissions quicker than its neighbours, and it held the most ambitious mid-term climate target of any rich nation until yesterday, when Denmark announced an 82% cut from 1990 levels by 2035.

Miliband called on countries to “go further and faster” in efforts to keep global heating to 1.5C; build confidence in the $300 billion a year climate finance goal agreed at last year’s Cop; and to build on the Brazilian Presidency’s pathway to a transition away from fossil fuels. “There is no answer to the climate crisis without action on this issue,” he said.

The speech attracted some scepticism from campaigners. Asad Rehman, chief executive of Friends of the Earth, said calls for global ambition from rich countries “ring hollow” without the support to back them up.

“Ed Miliband rightly criticised the forces of climate denialism, but just as deadly are the politics of delay at this most critical time,” he said. “What’s needed in these halls is the understanding that fairness goes hand in hand with the need for urgency.”

Fiona Harvey

If the world cannot solve the climate crisis within a capitalist system, “we should all go to bed and not wake up,” the influential economist Mariana Mazzucato has warned.

A small but growing number of economists have suggested that capitalism is part of the problem, and that a healthy planet is not possible within such a system. But Mazzucato, professor of economics at University College London and one of the most respected thinkers working on public governance globally, disagrees.

“It’s about how we do capitalism,” she said, speaking to the Guardian on the sidelines of the Cop30 conference. Governments have agency within the capitalist system, and how they behave over the climate crisis, and other environmental problems, is not decided by global economic forces over which they have no control, as some politicians seem to imply. It is governed by a series of choices, she said.

“Inaction is a choice. Corporate governance is a choice. [How we use] water is a choice – the fact that we have sewage in our rivers was a choice,” she said. “If there were deterministic forces [imposing strictures on governments], then I would be depressed.”

When faced with wars or threats to national security, governments act decisively – they put massive resources into their “military industrial complexes” with huge government budgets, which in turn spurs private sector investment and innovation. But on the climate crisis, they have stalled. That makes no sense, according to Mazzucato. “If you know how to do it with war, why the hell are you not doing it for climate when it’s actually the biggest security risk we have in the world?” she asked.

“Investing in both adaptation [to the impacts of extreme weather] and mitigation [the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions] is one of the best things we can also do for both national but also global security,” she said.

Mazzucato, who has advised several governments including Brazil, came up with a model of government organised into “missions”, similar to the model of the “moonshot” mission set by President John Kennedy in the 1960s. Once governments have set missions, and created the organisational structures necessary to achieve them, the public sector and private sector can work together to achieve the goals.

This idea was highly influential on UK prime minister Keir Starmer, who on taking office last year quickly announced his government’s five missions, which included health, crime, education and “making the UK a global clean energy superpower”.

But Mazzucato believes Labour has failed to follow through on these plans, which she blames on a lack of confidence. “Keir Starmer used the word [missions], but it doesn’t mean anything,” she said.

“There isn’t that confidence of working with businesses on publicly set goals,” she added. “Instead, it’s all about being ‘business friendly’. But what the hell does ‘business friendly’ mean? You’re going to probably get screwed if you’re just trying to be business friendly.”

Mazzucato would like to see governments use the power of their own procurement – budgets that run to hundreds of billions a year – to influence how businesses act. If companies can only be granted lucrative government contracts if they meet certain environmental criteria – such as cutting their greenhouse gas emissions, or using resources more efficiently – they will strive to meet them.

For instance, 80% of industrial wastewater is not recycled. “That’s a choice. Put it in a contract,” she advised, only allowing companies that achieve higher recycling rates to qualify for government contracts, or bailouts, or planning permission.

Unfortunately, she said, the UK was “really rubbish” on imposing such rules on companies.

Damian Carrington

Pope Leo, leader of the world’s 1.4bn Catholics, sent a powerful message to Cop30 here in the Amazon on Monday evening.

“Creation is crying out in floods, droughts, storms and relentless heat. One in three people live in great vulnerability because of these climate changes. To them, climate change is not a distant threat, and to ignore these people is to deny our shared humanity. As stewards of God’s creation, we are called to act swiftly, with faith and prophecy, to protect the gift He entrusted to us.”

Pope Leo said the Paris Agreement has driven real progress – the world was on target for 4C of global heating, compared to 2.6C today, though that is still far too high. He said it was not the Paris Agreement that is failing but “the political will of some”.

“True leadership means service, and support at a scale that will truly make a difference. Stronger climate actions will create stronger and fairer economic systems. Strong climate actions and policies, both are an investment in a more just and stable world.”

“We walk alongside scientists, leaders and pastors of every nation and creed. We are guardians of creation, not rivals for its spoils,” Pope Leo said. “Let [the Amazon] be remembered as the space where humanity chose cooperation over division and denial.”

As the first pope from the US, it is hard not to read such words as, in part, an implicit criticism of Donald Trump, who recently called the climate crisis a “con job” and pulled the US out of the Paris agreement.

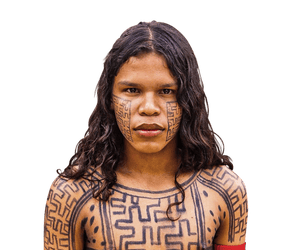

Wajã Xipai

Cop30 is the first UN climate negotiation to take place in the Amazon. This is how Wajã Xipai, a 19-year-old Xipai journalist, has experienced the summit so far.

I feel as if I’ve been swallowed. And in the creature’s stomach, I walk with the sensation of being drowned. My nose hurts, with the same pain we feel when we are struggling to breathe. That’s my perception of the blue zone of Cop30, the official area for the negotiations. The architecture makes me think of the stomach of an animal.

My eyes hurt, seeing so many people coming and going through the main corridor. This is the scene of a makeshift forest. On the walls are large paintings of a jaguar, a monkey, an anteater and a lizard. In the middle of the corridor are plants that resemble açaí palm trees, and below them, small shrubs. The place of nature within the blue zone is ornamental.

People are always running, never walking, always in a hurry. This accelerated rhythm, for a moment, courses through my body. For a moment I walk faster, think faster, breathe faster. The haste feels contagious. Then I realise: I can’t let myself be accelerated. My investigations aren’t rushed, my writing isn’t fast-paced, my listening isn’t either. The monster of haste from non-Indigenous society hasn’t entirely consumed me. I fear it nonetheless.

Before arriving in Belém, where Cop30 is taking place, I took a bus from Altamira to Alter do Chão. From there I took a boat along with scientists and leaders of Indigenous groups and riverside communities. It was a journey of many days, leaving the Tapajós River and then entering the enormous Amazon. When I disembarked, it was as if I had left a world where time opens up for another where time narrows.

Here at Cop30, everything seems urgent. The voices speak of the future, of goals, of funding, coming and going with the haste of those who have a clock in their soul. In the forest, nothing is rushed: the trees have a specific time to bear fruit, there is a certain moment to plant our crops. The seeds sprout when the earth is ready. Each bird sings in its own time – there is a tinamou that sings only at dawn, at noon and at dusk, and it never comes early or late. The forest understands time as a pact between beings.

Read the full story here.

Damian Carrington

Brazil is the world’s biggest exporter of beef, and that comes with a colossal carbon footprint, both from the methane that cattle burp and the forest destroyed to create pasture.

But the beef industry is here at Cop30, promoting a certification scheme for “low carbon beef”. The claim is based on managing the pasture’s soil so it absorbs more carbon.

The claim is dismissed by experts. Well-managed pasture is a good thing, but a long way from a “get out of jail free card” for big beef, said Jonathan Foley, head of Project Drawdown, which focuses on climate solutions.

“In terms of everyday things we use in our homes, beef is by far the biggest polluter, and no amount of soil carbon is going to offset that,” he told Bloomberg.

Fun fact: Even the very lowest impact meat, organic pork, is responsible for eight times more climate costs than the very highest impact plants, oil seeds. Comparing beef with plants overall, the figure is 166 times more.

First draft text revives shift away from fossil fuels

Fiona Harvey

When is a cover text not a cover text? When it’s a mutirão decision! The first draft of a potential outcome from the Cop30 has landed, put up on the UN web site on Tuesday morning, and it’s fascinating.

This will not be the only text from Cop30 – there are also texts on all of the other decisions that will be made at this Cop, in various stages of draft or not draft yet – but the mutirão decision takes in the “big four” issues that were too difficult to be included in the official agenda.

It also – surprisingly – includes lines referring to the “transition away from fossil fuels” among the options for an outcome. Discussion of this issue – which was agreed as the key resolution from Cop28 in 2023 – was effectively shut down last year in Baku, and in Belem has taken place only on the sidelines up to now.

The draft text is an elaboration of the “note” sent by Brazilian Cop president Andre Correa do Lago on Sunday night, formalised into the shape of something that could be gavelled through as a decision. In a letter on Monday night, do Lago suggested that the gavelling could be done after a meeting of ministers on Wednesday.

That would be astonishingly fast, and is frankly not likely. The discussions on the big four issues – finance; transparency; trade; and a response to the fact that current national climate plans (NDCs) are too weak to keep the 1.5C heating limit – have been going on since before the start of this conference last Monday, and the text shows – in its many options – that nations are still far from resolving them.

The draft mutirão text includes text that would allow for an annual review of countries’ NDCs, with a view to strengthening them to meet the 1.5C (2.7F) goal. That sounds a bit like the idea agreed at Glasgow’s Cop26 in 2021, for a faster “ratchet” to the Paris agreement – in the agreement, countries must return every five years with strengthened NDCs; at Glasgow, countries were invited to ratchet up their targets on a more frequent basis, but this was voluntary, and almost no countries availed themselves of the opportunity.

Countries are also invited – and here is a nod to China, which it is frequently noted tends to under-promise on its emissions targets and then over-deliver – to “aim to overachieve NDC targets”. China has been adamant at this Cop that there should not be a discussion of NDCs. Under the letter of the Paris agreement, such a review only needs to take place in three years’ time, under the second “global stocktake” – a mechanism for the assessment of NDCs every five years. But campaigners and many countries believe that waiting three years to be told that the NDCs are inadequate would waste yet more valuable time, and effectively nail shut the coffin of the 1.5C target.

Another option in the mutirão text is for a “Global Implementation Accelerator”, a new idea which would also be voluntary, and would “accelerate implementation, enhance international cooperation, and support countries in implementing their nationally determined contributions [NDCs]”. A third option is for a “Belem Roadmap to 1.5” which would set out what needs to be done to put the world on track to meet the Paris goals.

Mention of the “transition away from fossil fuels” falls under two options in the text, one the above first option of a response to the inadequacy of the NDCs, where it is accompanied by the other resolutions made at Cop28 of tripling global renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency by 2030, and the other an option for a “high-level ministerial round table on different national circumstances, pathways and approaches with a view to supporting countries to developed just, orderly and equitable transition roadmaps, including to progressively overcome their dependency on fossil fuels and towards halting and reversing deforestation”.

Finance is mentioned 26 times in the text, reflecting its centrality to all developing countries meeting in Belem. Developed countries are urged to set out their plans to provide financial assistance more clearly, in some of the five options on finance that are listed, including a ministerial round table on delivering the $1.3 trillion a year in climate finance promised to poor countries at last year’s Cop in Baku. Another is for a “Belem Global De-Risking and Project Preparation and Development Facility (“Belem Facility for Implementation”) to catalyze climate finance and implementation in developing country Parties by translating nationally determined contributions and national adaptation plans into project pipelines”.

That a text has been produced in which the transition away from fossil fuels makes it this far is itself a minor miracle. This could yet be watered down or rejected. But it is now looking likelier that some form of response to the 1.5C target and the NDCs – which could involve a strong financial element, as developing countries rightly insist that they cannot meet targets without more financial assistance than has yet been forthcoming – could be included in the Cop30 outcome.

Participation from industrial agricultural lobbyists at Cop30 is up 71% compared to Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, but has not hit the record high set at the vast Cop28 in Dubai, according to an investigation by Rachel Sherrington from DeSmog and my colleague Nina Lakhani.

More than 300 industrial agriculture lobbyists have participated at this year’s UN climate talks taking place in the Brazilian Amazon, where the industry is the leading cause of deforestation, a new investigation has found.

The number of lobbyists representing the interests of industrial cattle farming, commodity grains and pesticides is up 14% on last year’s summit in Baku – and larger than the delegation of the world’s 10th largest economy, Canada, which brought 220 delegates to Cop30 in Belém, according to the joint investigation by DeSmog and the Guardian.

One in four of the big agriculture lobbyists (77) are participating at Cop30 as part of an official country delegation, with a small subset (six) with privileged access to the UN negotiations where countries are meant to hash out ambitious policies to curtail global climate catastrophe.

Agriculture is responsible for a quarter to a third of global emissions and scientists say it will be impossible to meet the goals of the 2015 Paris agreement without radical changes to the way we produce and consume food.

Cattle ranching is the biggest driver of deforestation in the Amazon, followed by the industrial production of soy, which is mostly used for animal feed. Scientists have warned that as much as half of the Amazon rainforest could hit a tipping point by 2050 as a result of water stress, land clearance and climate disruption.

“More than 300 agribusiness lobbyists occupy the space at Cop30 that should belong to the forest peoples. While they talk about energy transition, they release oil into the Amazon’s basin and privatize rivers like the Tapajós for soy. For us, this is not development, it is violence,” said Vandria Borari of the Borari Kuximawara Indigenous Association of the Alter do Chão territory.

You can read more here.

Jonathan Watts

A marriage of Indigenous knowledge and mainstream science is essential for the maintenance of a healthy, habitable planet, according to a group of former state leaders, first peoples and influential climatologists at Cop30.

The self-styled “Planetary Guardians” also interrupted the planned schedule on Monday to deliver a message to climate summit negotiators that they must do more to phase out fossil fuels and deliver the 1.5C (2.7F) temperature target of the Paris Agreement.

The activism of venerable figures from academia, politics and the forest has been encouraged by the organisers of the conference, who have given more space than ever before to those on the intellectual and physical frontline of the climate crisis.

Planetary Guardians includes Christian Figueres, Johan Rockstrom, Carlos Nobre and Mary Robinson. The group describes itself as an independent collective elevating science to make the concept of planetary boundaries a measurement framework for the world.

At Cop30, many of the participants have expanded their reach to collaborate with Indigenous leaders and act as a scientific and moral advisory body for Brazil’s Cop30 presidency.

“There will be no peace among humans unless there is peace with nature,” said Juan Manuel Santos, the former president of Colombia who won a Nobel peace prize for his role in securing a peace deal with Farc guerillas after half a century of conflict.

“My own experience is that nobody has more knowledge and more experience and more effective ideas on how to protect nature than the Indigenous communities… I hope that in the room where they’re negotiating, they hear science and the Indigenous communities. Those two sources of information are absolutely indispensable if we want to save the planet.”

He was speaking at the planetary science pavilion of the conference alongside the Indigenous leader, shaman and philosopher Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, who spelled out the long struggle his people – who hold the largest Indigenous territory in Brazil – have had to fight to maintain their land and forest.

“We, the Indigenous humans, the original inhabitants have been protecting the force of nature for many, many years. We are protecting everything that non-Indigenous society is destroying,” he said. “I think the leaders who come here don’t want to change, but my message to them is this: ‘Respect and cherish our Amazon. Respect our forest, the soul of the forest, the soul of the earth. That’s all that we have.”

Scientists at the conference have warned the Earth is approaching – or may even have passed – several dangerous “tipping points” in the planetary system as a result of human emissions from coal, oil, gas and the destruction of forests.

Last week, the Science Panel on the Amazon released the most comprehensive scientific analysis ever conducted on the South American region, which revealed the world’s largest tropical forest was losing its globally important function as a regulator of water, temperature and carbon due to human pressure from land-grabbing, mining, logging and rising temperatures.

“Maintaining ecological and sociocultural connections is critical not only for safeguarding the Amazon but also for addressing the global climate crisis,” warned Brazilian climate scientist Carlos Nobre. “But we are on the edge of the point of no return in the Amazon.”

Kopenawa has previously warned in his own way of tipping points with the publication of a book, The Falling Sky, with anthropologist Bruce Albert. He welcomed the opportunity to talk beside other planetary guardians, whom he described as “influential warriors,” but he was grimly realistic about the prospect of anyone acting on his words.

He told the Guardian he had been talking about the threats to the forest for more than thirty years without being listened to and he did not expect the first climate summit in the Amazon to be any different: “ I don’t believe Cop30 will bring something for forest peoples that will be respected. They’re not going to say to us that no one is going to destroy, no one is going to mine on Indigenous land, no one is going to build roads on Indigenous land. They will continue attacking us, continue threatening the land, threatening our forest. They are used to doing evil.”

Hello, Ajit Niranjan here from Berlin – I’ll be hosting the liveblog this morning and my colleague Gabrielle Canon will take over this afternoon. We’re looking forward to bringing you the latest from the Cop30 climate summit.

Exclusion zone around conference expanded after protests

Damien Gayle

Walking on to Belém’s Parque da Cidade, the site of Cop30, yesterday morning revealed the extent to which the so-called “Indigenous Cop” has become a zone of exclusion for the very Indigenous people it is celebrating.

Soldiers and militarised police lined up to form human roadblocks, filtering access to the UN climate summit.

The closer you got towards the summit, the more heavily armed they became, until those closest to the venue carried shotguns and wore bandoliers of tear gas canisters. Throughout the day military helicopters buzzed ominously overhead.

Cop30 is the first in four years to be held in a democracy, but civil society groups’ hopes of being able to exercise their rights to the civic space have been increasingly disappointed.

Inside the tightly secured “blue zone”, where conference negotiations take place, the only permitted expressions of dissent were small demonstrations numbering no more than a few dozen youths politely chanting for an end to planet-killing industrialised ecocide.

And if the first Cop in four years to take place in a democracy seemed depressingly repressive business as usual on the civic space front, on the negotiations front things seemed little better.

A key issue at Cop30 – as at all recent Cops – is the issue of who pays.

Under article 9.1 of the Paris agreement, the basis for the past decade of climate negotiation, developed countries have an obligation to provide climate finance to developing countries based on their historical responsibility for carbon emissions.

This is the money that developing countries need to adapt to a rapidly warming world, and it is the money they need to respond to the climate-related disasters that it is bringing.

Developing countries want this money provided publicly by the global north. A major demand is for Cop30 to adopt a clear plan for the provision of finance implementation, including a formal process to track the progress of article 9.1.

Developed countries, particularly the UK, EU, Canada, Australia and Switzerland, have refused to engage meaningfully, say representatives of the global south.

The UK is key to unlocking this process, with Ed Miliband, the UK government’s energy and climate chance secretary, chairing the summit’s finance consultation, alongside his counterpart from the Kenyan government.

“If you can get an outcome on finance, it will unlock everything,” said Asad Rehman, chief executive of Friends of the Earth England, Wales and Northern Ireland, on the sidelines of the Cop30 negotiations on Monday.

But in common with their counterparts in the developed world, the UK government is apparently averse to any outcome that will create new commitments that could prove politically difficult domestically.

“There has been no progress on finance. They simply don’t want to talk about how the provision of finance is being implemented,” said Meena Raman, head of programmes at Third World Network.

“If we are at an ‘implementation Cop’, then money must be the central topic.”

The UK is also the main barrier to the much touted Belém Action Mechanism (Bam), the just transition framework that last week won the support of the G77 and China, collectively representing about 80% of the world’s population.

These positions expose the UK, which has in recent years presented itself as among the most ambitious of the wealthier nations when it comes to climate, as well as other European countries that have represented themselves as progressive on climate issues.

“This is the first Cop that the US aren’t here poisoning the process,” said Rehman. “Now will the UK show climate leadership?”