Our sister died because of our mum’s cancer conspiracy theories, say brothers

Social media investigations correspondent

BBC/Getty Images

BBC/Getty ImagesGabriel and Sebastian Shemirani watched with concern as their mother Kate rose to notoriety during the pandemic, eventually getting struck off as a nurse for promoting misinformation about Covid-19.

Then, their sister Paloma was diagnosed with cancer. Doctors told her she had a high chance of survival with chemotherapy. But in 2024, seven months later, she died – having refused the treatment.

The brothers blame their mother’s anti-medicine conspiracy theories for Paloma’s death at 23 – as cancer doctors tell BBC Panorama these beliefs are becoming more mainstream.

Kate Shemirani has not responded directly to the allegations we raised, but she has publicly blamed the NHS for her daughter’s death.

She and her ex-husband, Paloma’s father Faramarz Shemirani, wrote to us saying they have evidence “Paloma died as a result of medical interventions given without confirmed diagnosis or lawful consent”. The BBC has seen no evidence to substantiate these claims.

Paloma’s elder brother Sebastian says: “My sister has passed away as a direct consequence of my mum’s actions and beliefs and I don’t want anyone else to go through the same pain or loss that I have.”

Both brothers say they contacted me about Paloma in the hope they could prevent other deaths, and they believe social media companies should take stronger action against medical misinformation – which the BBC has found is being actively recommended on several major sites.

“I wasn’t able to stop my sister from dying. But it would mean the world to me if I could make it that she wasn’t just another in a long line of people that die in this way,” says Gabriel.

For Panorama and BBC Radio 4’s Marianna in Conspiracyland 2 podcast, I pieced together how this young Cambridge graduate came to refuse treatment that might have saved her life, following an online trail and interviewing people close to her.

And I found that conspiracy theory influencers such as Kate Shemirani are sharing once-fringe anti-medicine views to millions – which can leave vulnerable people at risk of serious harm.

It is getting harder to fight medical misinformation because of the prominence of figures such as Robert F Kennedy Jr, who have previously expressed unscientific views – says oncologist Dr Tom Roques, vice-president of the Royal College of Radiologists, which also represents cancer specialists.

When you have a US health and human services secretary “who actively promotes views like the link between vaccines and autism that have been debunked years ago, then that makes it much easier for other people to peddle false views,” he says.

“I think the risk is that more harmful alternative treatments are getting more mainstream. That may do people more active harm.”

Since becoming Health and Human Services Secretary, Mr Kennedy has said he is not anti-vaccine, and that he just supports more safety tests.

‘Conspiracy theories on the school run’

Paloma and her twin Gabriel, along with Sebastian and their younger sister, grew up in the small Sussex town of Uckfield, where they were exposed to conspiracy theories at home, her brothers say.

The “soundtrack” to their school runs, Gabriel says, was conspiracy theorist Alex Jones talking about how the Sandy Hook school shooting was staged or 9/11 “was an inside job”.

The brothers say it was their father who first got into conspiracy theories, which piqued their mother’s interest. The children absorbed outlandish ideas, including that the Royal Family were shape-shifting lizards, says Gabriel. “As a young child, you trust your parents. So you see that as a truth,” he says.

Sebastian believes their mum used her ideas as a way of controlling them. On one occasion, Kate Shemirani decided wi-fi was dangerous and switched it off at home, he says, ignoring his pleas that he had to submit GCSE coursework. “That only fed the joy that she had for using her irrational system of beliefs to control me,” he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAccording to her sons, Kate Shemirani’s anti-medicine views were accelerated in 2012, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Even though she had the tumour removed through surgery, she credits alternative therapies for her recovery and says online how she used a programme including juices and coffee enemas to become “cancer-free”. She doesn’t use the word cured.

Paloma absorbed some of these ideas, says Chantelle, one of her best friends from school. “Paloma spoke about her mum curing herself, and she believed sunscreen could cause cancer. I remember she used to get burned so badly at school,” she says.

After their parents split up, Gabriel and Sebastian became estranged from their mother. But Paloma maintained contact with her, even when she went off to study at Cambridge in 2019.

Ander Harris

Ander Harris“Paloma’s strategy was to appease, to be sweet, to try and win the love that she hadn’t been granted earlier,” says Sebastian.

Messages Paloma shared with her then-boyfriend Ander Harris – and which he has shared with the BBC – reveal a relationship with her mother that had moments of love and care, but also times when Paloma saw it as toxic and abusive.

Over Christmas 2022, she told Ander her mother was blaming her for other children not coming home for Christmas. “I’m so so so sick of being abused”, she wrote, suggesting with an expletive that this treatment happened all the time.

![A graphic showing texts between Paloma and her boyfriend Anders, with Paloma telling him: "I'm so so so sick of being abused all the [REDACTED] time I literally sacrificed my own plans to get here and now I'm just sat taking [REDACTED] from her and crying at the same time".](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/480/cpsprodpb/1f8b/live/4d0634d0-4ea8-11f0-a466-d54f65b60deb.png.webp)

Her mother kept coming into her room and “being mean”, Paloma said in one message, adding that her mother had hit her. Paloma left for a friend’s house. She later shared her parting message to her mother with Ander, saying it was “the last straw. You hurt me every time I let you in and I never ever will again. I’m beyond hurt”.

Back at university, Paloma seemed to be moving away from her mother’s beliefs at times. Chantelle says she began eating meat and using fluoride toothpaste. But both Chantelle and Ander say she remained sceptical about the Covid-19 vaccine and refused to have it.

‘A concern regarding parental influence’

In late 2023, not long after graduating, Paloma began to have chest pains and breathing difficulties. She went to the hospital.

Doctors suspected a tumour, but Ander says he and Paloma, “one of the smartest people I’ve ever met”, were hopeful at first that it would turn out not to be malignant. Paloma made light of it, nicknaming the tumour “Maria the Lung Mass”, he says.

But on 22 December, Paloma and Ander went to Maidstone Hospital where doctors gave her the diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Untreated, this type of cancer can be fatal, but doctors told Paloma she had an 80% chance of recovery if she had chemotherapy.

Paloma told her mother the news. Ander says Paloma still wanted her support, even though their relationship had recently been through a rough patch. Kate Shemirani said she would come to the hospital. Paloma was worried about seeing her, though, and spoke to medical staff about her concerns, her then-boyfriend says.

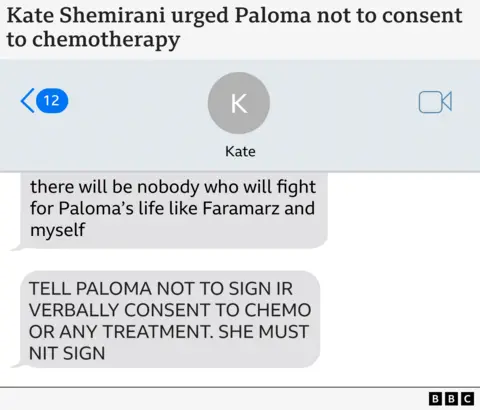

Evidence seen by the BBC suggests Paloma’s thinking could have been influenced by her mother during the two days she was an inpatient at Maidstone Hospital.

Kate Shemirani texted Ander to say: “TELL PALOMA NOT TO SIGN [OR] VERBALLY CONSENT TO CHEMO OR ANY TREATMENT.”

Ander and his own mother, who was also there, raised concerns with hospital staff about Kate Shemirani’s beliefs and her relationship with Paloma.

Medical staff discussed safeguarding concerns about Paloma among themselves and wrote that they had “a concern regarding parental influence” on her. But they also thought that she did have the capacity to make her own decisions.

For advice, Paloma reached out to a former partner of Kate Shemirani called Patrick Vickers. Paloma had a good relationship with him, Ander says. He is also an alternative health practitioner.

When Paloma asked him about the “80% chance of cure” the doctors had said chemotherapy would offer, Mr Vickers said that was “exaggerated”. He encouraged her to start Gerson therapy and to maybe consider chemotherapy if her symptoms did not improve after six weeks.

Mr Vickers told us that any “assertions that I played a role in her [Paloma’s] death are legally inaccurate”. He also shared documents with the BBC in support of Gerson therapy.

Gerson therapy involves a strict plant-based diet, along with juices, supplements and coffee enemas. Some people claim – without scientific evidence – it can be used to treat a range of cancers.

Gabriel & Sebastian Shemirani

Gabriel & Sebastian ShemiraniPaloma was worried about the negative side effects of chemotherapy, Ander tells me, as it can cause fatigue, sickness, hair loss and affect fertility. Nursing staff spoke to Paloma about egg-freezing and wigs when she was diagnosed.

But the charity Cancer Research UK says Gerson therapy can also have severe side effects, including dehydration, inflammation of the bowel, and heart and lung problems.

At some point during the two days in hospital, Ander says, Paloma made up her mind. She decided not to pursue chemotherapy – at least for the time being – and would try Gerson therapy to start with.

On 23 December, Kate Shemirani sent Ander a voice note giving him instructions to drive Paloma to her house, saying she had arranged doctors for her. She suggested Paloma’s time with a friend she wanted to see should be limited on Christmas Day – and said in the message that they could “see her for maybe half an hour or whatever here, or they can do it on FaceTime”.

Ander says he felt he could not argue. Paloma “was in fight or flight and really just wanted to be taken care of and, you know, not have to make the hard decisions”, he says. “Her mum kind of swooped in and took advantage of that.”

Promoting misinformation

Kate Shemirani promotes ideas which she recommended to her daughter to a wider public online. A former NHS nurse in the 1980s, she calls herself “the Natural Nurse” on social media.

On her website, she sells apricot kernels for their “potential health benefits” along with nutritional supplements, and offers information and advice.

She charges about £70 for an annual membership to her site, and charges patients – including those with cancer – £195 for a consultation and personalised 12-week programme.

On social media she posts videos promoting her products and sometimes criticises “ill-informed people” for treating cancer with chemotherapy, or “pumping mustard gas into their veins” as she characterises it.

When the Covid pandemic hit in 2020, Kate Shemirani was one of many conspiracy theory influencers who found a wider audience. Her beliefs appeared to have evolved from alternative health ideas to sprawling anti-establishment conspiracy theories.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe promoted the false ideas that the pandemic was a hoax, that vaccines were part of a plan to kill lots of people, and that doctors and nurses should be punished for their part in it all.

In 2021 a Nursing and Midwifery Council panel determined that Kate Shemirani should be struck off as a nurse for promoting misinformation about the pandemic. Several social media companies also suspended her profiles for promoting misinformation. “She went into obscurity,” says Sebastian.

But once Elon Musk bought X in 2022, lots of conspiracy theory accounts were reinstated, including Kate Shemirani’s. She was also reinstated on Facebook and she joined TikTok.

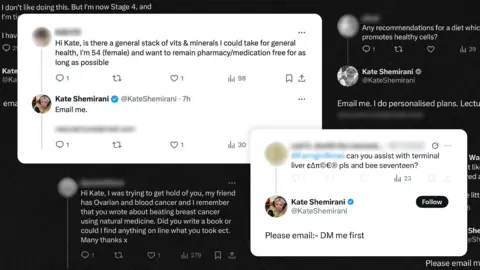

Her audience has grown again – in the past six months she has had her content viewed more than four and a half million times across the major social media sites. I have found dozens of comments on X where she encourages people to get in touch, including those with cancer.

TikTok says it has now banned Kate Shemirani’s account for violating medical misinformation policies. According to Meta, Instagram and Facebook do not allow harmful medical misinformation. X did not respond.

Life support switched off

Paloma continued on Gerson therapy. Some of her friends noticed how she became more and more unwell.

On one video call, Chantelle says, Paloma said she had a new lump in her armpit, and her mother had told her it meant that the cancer was going out of her body. “I knew she was really struggling,” she says, adding that Paloma told her she had lost control of her bodily functions.

But she says Paloma also said she felt pressured by doctors and friends to reconsider her decision to pursue alternative therapies on their own. Chantelle says she did not agree with the alternative therapy either, but wanted to be there for her friend.

Paloma had mentioned other people trying to change her mind and discussed “cutting them off”, Chantelle adds. “I thought I don’t want to be cut off especially when she’s struggling like this.”

Over the months that they spoke on the phone, Chantelle says she noticed that Kate Shemirani was “taking very good care of Paloma”. But she does not think Paloma would have made the same decisions without her mother.

“I don’t think her ideology was strong enough to make those decisions is my personal belief. People have different opinions about these things, but I think her mum played a massive, massive role into it,” Chantelle says.

In March 2024, Paloma ended her relationship with Ander. Other friends and family felt that Kate Shemirani was isolating Paloma from them.

Gabriel says he asked to meet Paloma not long after she was diagnosed but his sister said she could not go out because of the “bad air”. Their mother had convinced her that the “damp air” would cause her to become more ill, he says.

Sebastian and Gabriel were so worried that Gabriel started a legal case. He was not arguing Paloma did not have capacity, but he wanted an assessment of the appropriate medical treatment for her.

But events overtook them and the case ended without a conclusion in July – because Paloma had died.

Gabriel & Sebastian Shemirani

Gabriel & Sebastian ShemiraniGabriel only learned of his sister’s death several days afterwards, in a phone call from their lawyer. He had to break the news to his brother. “It’s like being burnt alive and you feel the searing pain every time it comes out of your mouth,” Gabriel says.

Sebastian says he blamed himself. “I haven’t come to terms with that at all,” he says.

When Ander heard, “I broke,” he says. “I was just, like, screaming and crying at the top of my lungs.”

Paloma had suffered a heart attack caused by her tumour. She was taken to hospital, but after several days, her life support was switched off.

An inquest is due to begin next month to establish the circumstances surrounding Paloma’s death.

Kate Shemirani has promoted a range of unproven theories on social media and fringe political podcasts about how she believes Paloma was murdered by medical staff – and that this was followed by a cover up. The BBC has not seen evidence to support these claims.

Paloma’s death was devastating for her family and loved ones. But for Sebastian and Gabriel, it is also a warning of the potential consequences for people who believe anti-medicine conspiracy theories like their mother’s.