Extreme Heat in U.S. Schools Disproportionately Affects Marginalized Students

September 4, 2025

5 Min read

Children of marginalized communities learn in the hottest classrooms

The first national study of this type shows that children of marginalized communities are more exposed to extreme heat events

A fan moves in a third year classroom in Denver, Colorado, October 8, 2024.

RJ Sangosti / Medianews Group / The Denver Post via Getty Images

A heat wave can transform a classroom without suitable cooling into an oven. Excessive heat can interfere with the learning process of any child, but in the United States, the most affected students are disproportionately from low-income families and colored communities.

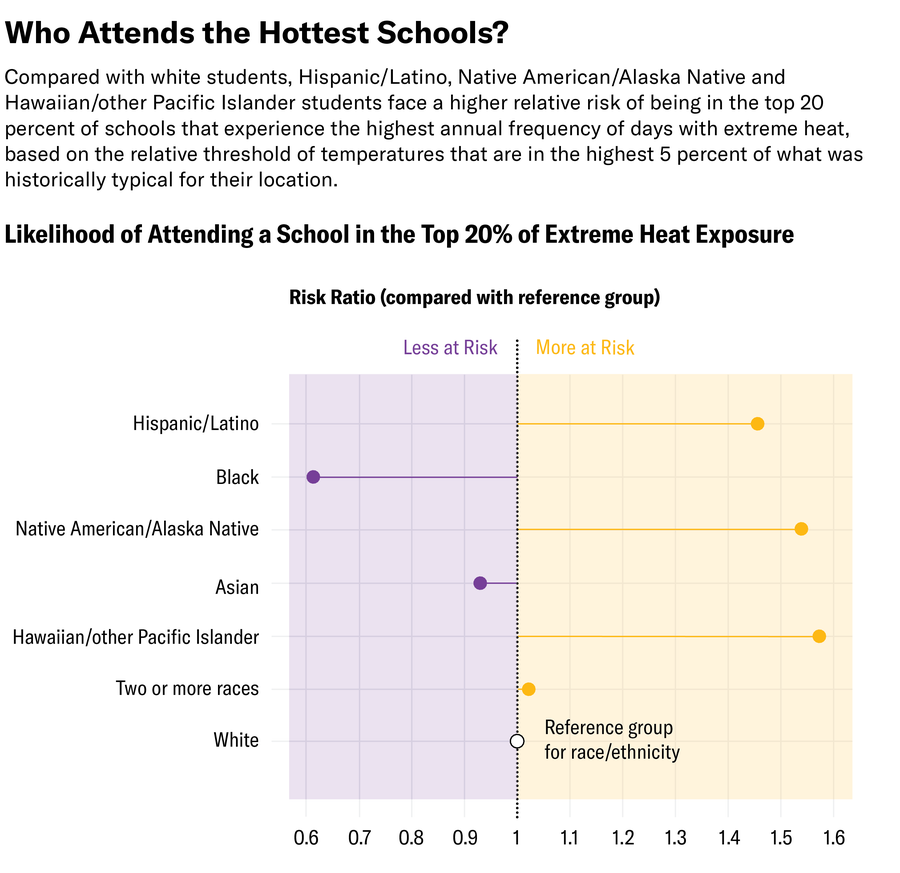

A recent study published in SSM HEALTH Population Now has quantified these inequalities in American public schools for the first time. Researchers have discovered that Hispanic / Latinos, Amerindian / native students of Alaska and Hawaiians / other Pacific islanders, as well as children who are eligible for a free lunch or at a reduced price, are much more likely than their white peers and wealthy to frequent schools located in places that experience the highest number of days with extreme warmth.

“This is information that we could probably have concluded without the data,” said the co-author of the Sara Soroka study of the University of California in Santa Barbara. “But we hope that this study can be used to create and implement policies to mitigate children’s heat exposure as the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events continue to increase.” Due to the increase in global temperatures caused by the combustion of fossil fuels, heat waves in the United States occur more often, lasts longer and spreading in spring and autumn. Although it is well known that people from the minority racial and ethnic groups are generally more exposed to heat than people in white and richer communities, there was no data on how exposure disparities take place in schools.

On the support of scientific journalism

If you appreciate this article, plan to support our award -winning journalism by subscription. By buying a subscription, you help to ensure the future of striking stories about discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

To measure the disparities, Soroka and its co-author have mapped the temperature data on each contiguous United States public school, they defined extreme heat in two ways: an absolute threshold of days when the outside temperature was greater than 90 degrees where temperatures were in the highest 5% of what was historically typical for a given location. Such a relative measure is useful because, for example, Dallas sees temperatures above 90 degrees F for most summer months; Higher temperatures are much less common in, let’s say, Seattle. Places where hot temperatures were historically rarer often have schools that lack air conditioning.

The researchers then classified schools nationwide and identified those who have the highest frequency of days with extreme heat. Then, they compared the demography of students attending these heating schools with students in cooler environments.

The results have shown that the Hispanic and Amerindian / Aboriginal students of Alaska were over -represented in schools that were most exposed to prolonged heat or extreme heat events. Researchers also found that low -income students – defined as those eligible for a free or reduced lunch – were disproportionately concentrated in these same schools.

Researchers did not find that black students are over -represented in schools confronted with the greatest number of extreme heat days under relative measurement, but these students were overrepresented in schools that have known most of these days under absolute measurement, depending on the 90 degrees F. Soroka says that this reflects the higher concentration of black students and low -income in the places in southern places – Warm than the local average is less common. The authors also note that black students are less represented in schools in the Northeast and Midwest. In both regions, changes in the occurrence of extreme heat events have been more visible and schools were less likely to have cooling systems in place.

The results are consistent with other studies showing that “cooled” districts – places that have historically been discriminated against and neglected with regard to public services – are generally warmer than richer districts due to a lack of green areas, air conditioning and heat resistant buildings, said Ladd Keith, director of the resilience of heat resilience at the University of Arizona. “The heat is actually the killer of the number one weather in the United States, and it has not been recognized, really as danger in the past two years,” said Keith. “The fact that he aggravates all these other social inequalities in an invisible way, for many people, is one of the most dangerous things on this subject.”

The new study does not take into account the existence or quality of air conditioning equipment in schools where extreme heat is common; Public data on this subject is seriously lacking. But the US Government Accountability Office estimated in 2020 that around 36,000 schools across the country had to replace or improve their CVC systems (heating, ventilation and air conditioning). This problem tends to affect schools which had historically exposed to heat and which were therefore not designed to accommodate large cooling systems, says Keith.

With global temperatures and extreme heat events constantly increasing across the country, schools will have to monitor temperature changes and adapt, says Keith. But he notes that “schools that are financially attached will have more difficulty upgrading their air conditioning units – and even start them for the first time – without national or federal support”.

How heat affects learning

Studies have shown that heat reduces the ability of children to learn, decreases their productivity and exposes them to risks such as heat stroke and dehydration. At the same time, the school closures caused by extreme heat affect children’s access to education – and even meals, for those who receive a free or reduced lunch. There are no data available on the frequency of American schools due to extreme heat, but UNICEF estimates that in 2024, around 242 million students in 85 other countries or territories had their education disturbed by extreme climatic events, including heat waves.

And exposure to heat does not end in school for many children of low -income families and colored communities, explains Amie Patchen, public health researcher at Cornell University. “Children of low -income communities who are more likely to be in schools without air conditioning are also more likely to go home in places without him.”

Patchen says that the new study highlights the double vulnerability of children in marginalized communities and that this data is important to design more research focused on inequalities in access to air conditioning, as well as on heat resistant infrastructure in schools.

Even if the National Information on Integrated Health Information System (a federal government information system to help decision-makers protect people from heat) and centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognize children as a risk group with regard to heat, there are no national policies that guide schools on how to react beyond the cancellation of prices during heat waves.

Children in cities risk the highest risk due to the effect of the urban heat island, which means that city temperatures are higher than in surrounding suburban areas. This effect means that school authorities in affected areas must be particularly cautious in monitoring temperature changes, explains Kristie Ebi, a global health scientist at Washington University.

For Keith, school authorities and local governments and states must take protective measures to prevent disasters such as the heat of the northwest of the Pacific of 2021 – an extreme meteorological event that attracted local governments and schools in the region largely not prepared for unprecedented heat. Keith notes that outdoor sports continued at the start of the heat dome until local officials realize gravity. But some students had already been exposed to dangerous temperatures in the midst of events sanctioned by schools.

Until there is a national strategy to improve school conditions and better ensure children’s safety, says Keith, local governments must learn errors and experiences elsewhere. “My advice,” he says, “is to learn places that have been caught up in the deprived and to make your proactive planning before it happens to you.”