First Human Genome from Ancient Egypt Sequenced from 4,800-Year-Old Teeth

The 4,800 -year -old teeth produce the first human genome in ancient Egypt

Forty years after the first effort to extract mom DNA, the researchers finally generated a complete sequence of a former Egyptian, who lived when the first pyramids were built

The ancient Egyptian kingdom (2686-2125 BC) produced many lasting artifacts – but few DNA has survived.

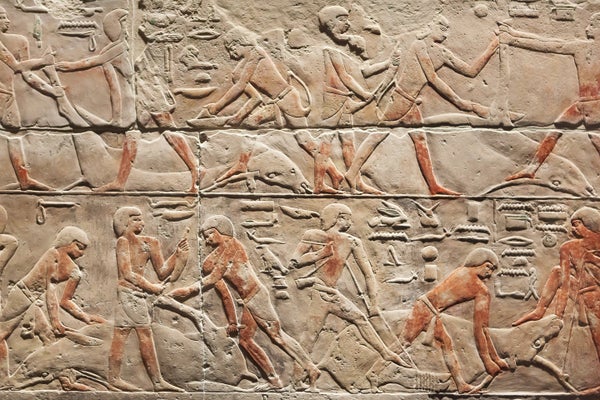

Photo Azoor / Alamy Photo

The teeth of an elderly man who lived roughly when the first pyramids were built gave the first sequence of the complete human genome of ancient Egypt.

The remains are 4,800 to 4,500 years old, overlapping with a period of Egyptian history known as the ancient kingdom or the age of the pyramids. They house signs of ancestry similar to those of other former North Africans, as well as people from the Middle East, according to researchers Nature.

“It’s incredibly exciting and important,” said David Reich, a geneticist of the population at the Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, who was not involved in the study. “We always hoped that we would get our first ancient Mummies DNA.”

On the support of scientific journalism

If you appreciate this article, plan to support our award -winning journalism by subscription. By buying a subscription, you help to ensure the future of striking stories about discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

Many laboratories have tried to extract the DNA from ancient Egyptian remains. In 1985, the evolutionary geneticist Svante Pääbo reported the first old DNA sequences of any human: several thousand DNA letters of an Egyptian mummy 2,400 years old of a child. But Pääbo, who won a Nobel Prize in 2022 for other works, later realized that the sequences were contaminated by modern DNA – perhaps his. A 2017 study generated limited genome data from three Egyptian mummies that lived between 3,600 and 2,000 years.

The hot hot-African climate accelerates DNA rupture, and the mummification process could also accelerate it, said Pontus Skoglund, paleogeniticist to the Francis Crick Institute in London who co-directed the Nature Study, during a press briefing. “Mummified individuals are probably not a great way to preserve DNA.”

The ceramic ship in which the remains of the naked individual were discovered.

The remains that the Skoglund team led to generalized mummification before the date: the person was buried instead in a ceramic pot, a high status sign, but no elite. The remains were found on an archaeological site called Nuwayrat, 265 kilometers south of Cairo along the Nile. The teeth and bones were discovered in 1902, when Egypt was under British colonial domination. They were given to institutions in Liverpool, in the United Kingdom, where they have since been, even surviving German bombings during the Second World War.

Weak expectations

Skoglund says that his expectations were weak when his team extracted DNA from several teeth from the Nuwayrat individual. But two samples contained enough old authentic DNA to generate a complete genome sequence. The chromosomes sequences indicated that the leftovers belonged to a male.

The majority of its DNA looked like that of the first farmers of the Neolithic period of North Africa about 6,000 years ago. The other people most closely twinned in Mesopotamia, a historic region of the Middle East which housed the ancient Sumerian civilization, and was the place where some of the first writing systems emerged. It is not clear if this implies a direct genetic link between members of Mesopotamian cultures and people in ancient Egypt – also lit by similarities in certain cultural artefacts – or if the Mesopotamian ancestry of man has arrived by other sampled populations, say the researchers.

The rest of the bones of the ancient Egyptian man revealed more details about his life. Evidence of arthritis and osteoporosis suggest that he died at an advanced age for the time, perhaps in the sixties. Other signs of wear and wear indicate a life of physical work, seated in hard surfaces. Based on this and the imagery of other tombs of this period, he could have been a potter, said co-author Joel Irish, bioarchaeologist at the University of Liverpool John Moores, during the press briefing.

“The publication of a set of data from the whole genome of an ancient Egyptian constitutes a significant realization in the field of Molecular Egyptology,” explains Yehia Gad, geneticist of the National Center for the Research of Egypt in Cairo, which clearly congratulates researchers to present the Provance of remains. But he stresses that the genome comes from an individual and may not completely represent the egypt’s genes of the old Egypt, which was probably a crucible of different ancestors.

For this reason, researchers are impatient of older data on the Egyptian genome – perhaps even a mummy. The progress of the technology of the ancient generation and local capacities – GAD supervises an old DNA laboratory at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Cairo – means that it will not yet take 40 years.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first publication July 2, 2025.