Gender ambiguity was a tool of power 4,500 years ago in Mesopotamia

Today, trans people face politicization of their lives and defamation by politicians, the media and part of society at large.

But in certain moments of history first civilizationspeople of diverse genders were recognized and understood in an entirely different way.

Already 4,500 years ago in Antiquity Mesopotamiafor example, gender diverse people held important roles in society with professional titles. These included the servants of the cult of the major deity Ištar, called assinnuand high-ranking royal courtiers called ša rēši.

What the ancient evidence tells us is that these people held positions of power. because of their gender ambiguity, not in spite of it.

Where is Mesopotamia and who lived there?

Mesopotamia is a region consisting mainly of modern Iraq, but also parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran. Part of the Fertile CrescentMesopotamia is a Greek word which literally means “land between two rivers”, referring to the Euphrates and the Tigris.

For thousands of years, several major cultural groups have lived there. Among them were the Sumerians and later Semitic groups called Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians.

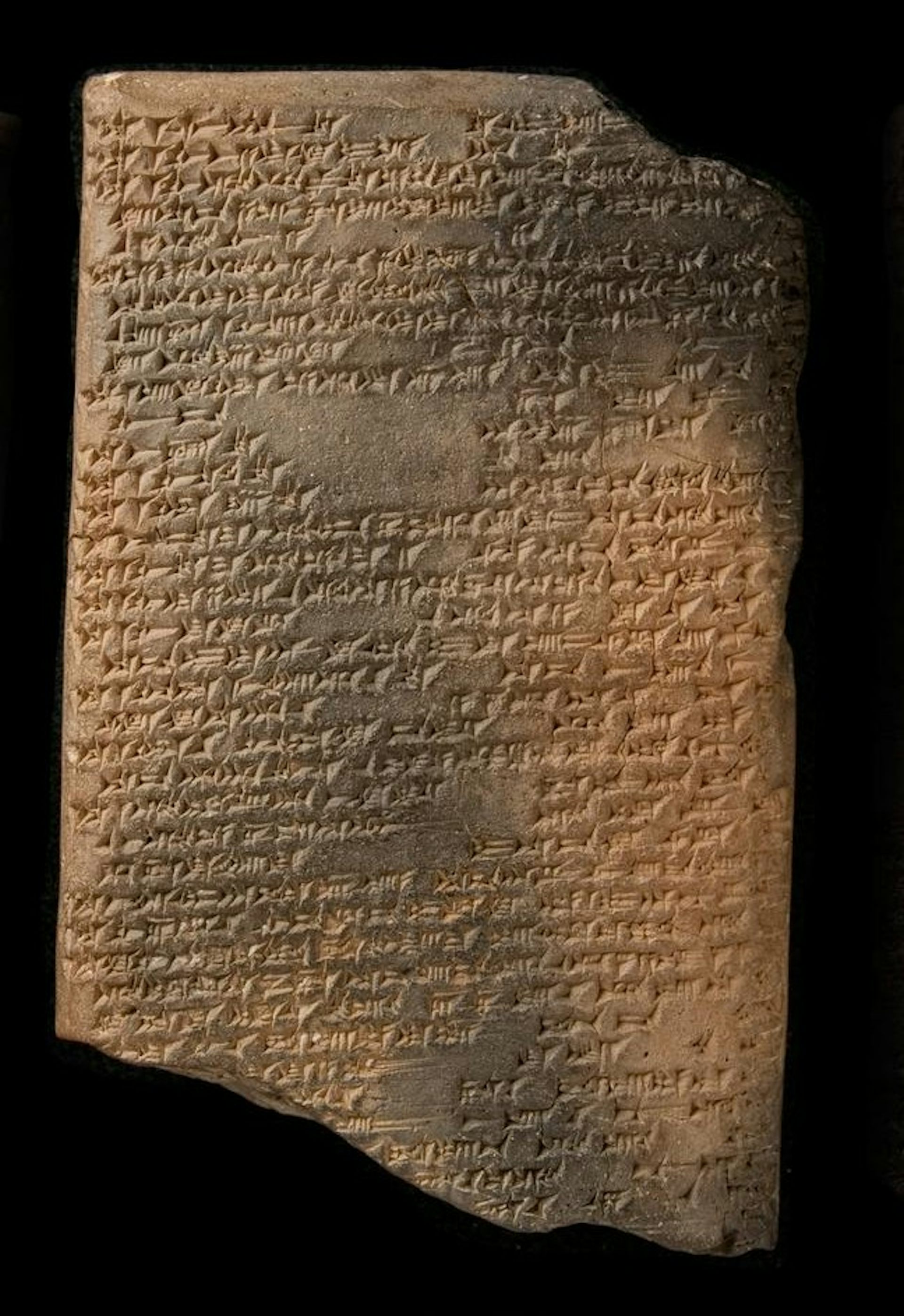

The Sumerians invented writing by creating corners on clay tablets. The script, called cuneiformwas designed to write the Sumerian language, but would be used by later civilizations to write their own dialects of Akkadian, the first Semitic language.

Who were the assinnu?

THE assinnu were the religious servants of the main Mesopotamian goddess of love and war, Ištar.

The queen of the sky, Ištar was the precursor of Aphrodite and Venus.

Also known by the Sumerians as Inanna, she was a warrior god and held the ultimate political power to legitimize kings.

She also dealt with love, sexuality and fertility. In the myth of her journey to hellhis death puts an end to all reproduction on Earth. For the Mesopotamians, Ištar was one of the greatest deities in the pantheon. Maintaining its official cult ensured the survival of humanity.

Like his companions, the assinnu were responsible for pleasing and caring for her through religious rituals and the upkeep of her temple.

The title assinnu is a Akkadian word related to terms meaning “woman-like” and “man-woman,” as well as “hero” and “priestess.”

Their gender fluidity was bestowed on them by Ištar herself. In a Sumerian hymnthe goddess is described as having the power to

transform a man into a woman and a woman into a man

change one into the other

dress women in men’s clothing

dress men in women’s clothing

put spindles in the hands of men

and give weapons to women.

THE assinnu were considered by some early researchers to be a type of religious sex worker. This is however based on first assumptions on gender diverse groups and is not well supported by evidence.

The title is also often translated as “eunuch”, although there is no clear evidence that these were castrated men. Although the title is predominantly masculine, there is proof of wife assinnu. Indeed, various texts show that they resisted the binary gender.

Their religious importance allowed them to possess magical and curative powers. An incantation states:

May your assinnu stay there and extract my illness. May he make the evil that has seized me pass through the window.

And a neo-Assyrian omen teaches us that sexual relations with a assinnu could bring personal benefits:

If a man approaches a murderer [for sex]: restrictions will be relaxed for him.

As followers of Ištar, they also exercised powerful political influence. A Neo-Babylonian almanac states:

[the king] If he touches the head of an assinnu, he will defeat his enemy, his land will obey his command.

Having their gender transformed by Ištar herself, the assinnu could walk between the divine and the mortal while maintaining the well-being of the gods and humanity.

Who were the ša rēši?

Usually described as eunuchs, ša rēši were the king’s servants.

Court “eunuchs” have been recorded in many cultures throughout history. However, the term did not exist in Mesopotamia and the ša rēši had their own distinct title.

The Akkadian term ša rēši literally means “one of the chiefs” and refers to the king’s closest courtiers. Their functions within the palace varied and they could hold several high-ranking positions simultaneously.

The evidence for their gender ambiguity is both textual and visual. There are different texts that describe them as sterile, such as an incantation that says:

Like a ša rēši that does not generate, may your seed dry up!

THE ša rēši are always represented beardless and contrast with another type of courtier called ša ziqni (“the bearded one”)who had descendants. In Mesopotamian cultures, a beard signified virility, and so a beardless man would go directly against the norm. Again, reliefs show the ša rēši wore the same attire as other royal men and were thus able to display their authority alongside other elite men.

One of their main duties was to supervise the women’s quarters of the palace – a place of very restricted access – where the only man allowed entry was the king himself.

Because the king trusted them so much, they were not only able to take on martial roles as guards and charioteers, but also to lead their own armies. After their victories, ša rēši gained ownership and government over the newly conquered territories, as evidenced by one of these ša rēši who erected his royal stone inscription.

Because of their gender fluidity, ša rēši were able to transcend the boundaries not only of gendered space, but also those between leader and subject.

While early historians viewed these figures as “eunuchs” or “cult sex workers,” evidence shows that it was because they lived without being bound by the gender binary that these groups were able to occupy powerful roles in Mesopotamian society.

As we recognize the importance of transgender and gender diverse people in our communities todaywe can see a continuity of respect given to these first figures.

This edited article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.