Millions Joined SETI@home Project, Now Astronomers Zero In on 100 Promising Signals

SETI@home, the pioneering distributed computing project launched in 1999 that mobilized millions of volunteers to analyze radio signals from space, produced some 12 billion detections—brief bursts of energy that stood out from the background noise—by scanning observations recorded at the now-defunct Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Astronomers at the University of California, Berkeley, have now narrowed the data set down to about 100 signals worth tracking with powerful radio telescopes.

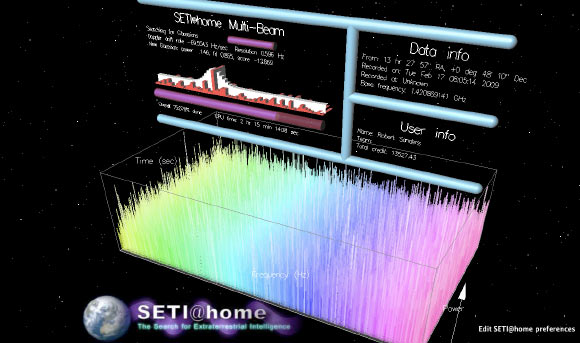

A screenshot of the SETI@home user interface on a desktop computer in 2009. Image credit: Robert Sanders / UC Berkeley.

Between 1999 and 2020, millions of people around the world lent their personal computers to the SETI@home project to search for signs of advanced civilizations in our Milky Way.

They downloaded SETI@home software onto their computers and allowed it to analyze data recorded at the Arecibo Observatory to find unusual radio signals from space.

In total, these calculations produced 12 billion detections.

After 10 years of work, the SETI@home team has now finished analyzing these detections, classifying them into approximately one million candidate signals and then down to 100 that deserve a second look.

“SETI@home is a SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) radio project, which looked for several types of signals in recorded data,” said SETI@home project co-founder Dr. David Anderson, a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Most of these data were recorded commensally at the Arecibo Observatory over a 22-year period.”

“Further data from the Parkes and Green Bank observatories were provided by the Breakthrough Listen initiative.”

“Most radio SETI projects process data in near real time using special analyzers installed on the telescope.”

“SETI@home takes a different approach: it records digital data in the time domain (also called baseband) and distributes it over the Internet to a large number of computers that process the data, using both CPUs and GPUs.”

The promising SETI@home signals are currently being re-observed with China’s Five Hundred Meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) to see if they repeat or exhibit characteristics inconsistent with the noise.

“I don’t expect to find a real extraterrestrial signal,” Dr. Anderson said.

“If there was a signal above a certain strength, we would have found it.”

The multi-step analysis of SETI@home, described in two articles in Astronomical Journaloffers both a technical roadmap and a warning for future technosignature hunts.

The first of these papers detailed how the project’s distributed network of home computers applied advanced signal processing to raw radio data in the time domain, using techniques such as discrete Fourier transforms to search for frequency patterns that might betray a persistent alien beacon.

A follow-up paper focused on the complex task of distinguishing potential signals from the overwhelming background of terrestrial interference—from satellites, broadcast stations, and even microwave ovens—by identifying clusters of detections consistent with their origin from a single location in the sky across multiple observations.

Future efforts could expand on the SETI@home model by distributing new telescope data sets through platforms like BOINC – the voluntary computing infrastructure that SETI@home helped launch – to harness public processing power again, this time with more sophisticated tools and faster networks.

“I think the search for extraterrestrial intelligence continues to capture people’s imaginations,” said SETI@home project director Dr. Eric Korpela, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley.

“I think you could still get significantly more processing power than what was used for SETI@home and process more data with wider internet bandwidth.”

“The biggest problem with such a project is that it requires personnel, and personnel means salaries. It is not the cheapest way to achieve SETI.”

_____

David P. Anderson and others. 2025. SETI@home: Data analysis and results. A.J. 170, 111; doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ade5ab

EJ Korpela and others. 2025. SETI@home: Data acquisition and front-end processing. A.J. 170, 112; doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/ade5a7