How 30 years of chip transitions paved the way for the spectacular Apple Silicon era

With the announcement that MacOS Tahoe will be the latest Mac OS version to support Intel Mac, Apple preparing to close the books on the third transition of chips in the history of Mac.

He doesn’t get much attention, but Apple is absolutely the best business in the world to pick up issues and move its platforms elsewhere. During its 41 years of existence, the Mac worked on four entirely different processor architectures (not to mention two different operating system foundations), while remaining more or less the same familiar mac that we know and love.

It is not an easy feat to accomplish once, even less three times. Apple has become very good in this area. Twenty years ago, it was the transition to Intel. Five years ago, the transition to Apple Silicon started. And of course, in the fogs of times when I was a whole new hiring in one of the predecessors of Macworld, Apple made the jump for the very first time.

Hardly won lessons

When I wrote on the history of the transitions of the Mac fleas while the rumors of Apple Silicon’s transition turned, I made it grow to emphasize that Apple had been there, did this and learned many lessons. My only concern was that there was someone in Apple who had experienced the old transitions, or if the company should understand it again.

After the publication of this story, I heard of someone inside Apple who assured me that, yes, there were still people who had been launched who had been there when this very first transition from the chip occurred in the 1990s. This type of institutional memory was of vital importance for Apple’s transitions in 2005 and 2020, as it turned out.

The original Mac is delivered with a Motorola 68000 processor. The 68K was used on all kinds of video games, some Atari computers, as well as the Mac. But in the early 1990s, Apple was frustrated by the slowness of its flea manufacturer’s improvements and realized that the fate of its platform depended on someone else’s success or failure.

This story will continue to repeat.

Apple was doing its own research on fleas at the time when, in the most improbable events, its IBM rival approached the company to collaborate on a design of new generation fleas. With Motorola almost Jilted added as a partner, the AIM alliance began to build a new set of fleas that would become PowerPC.

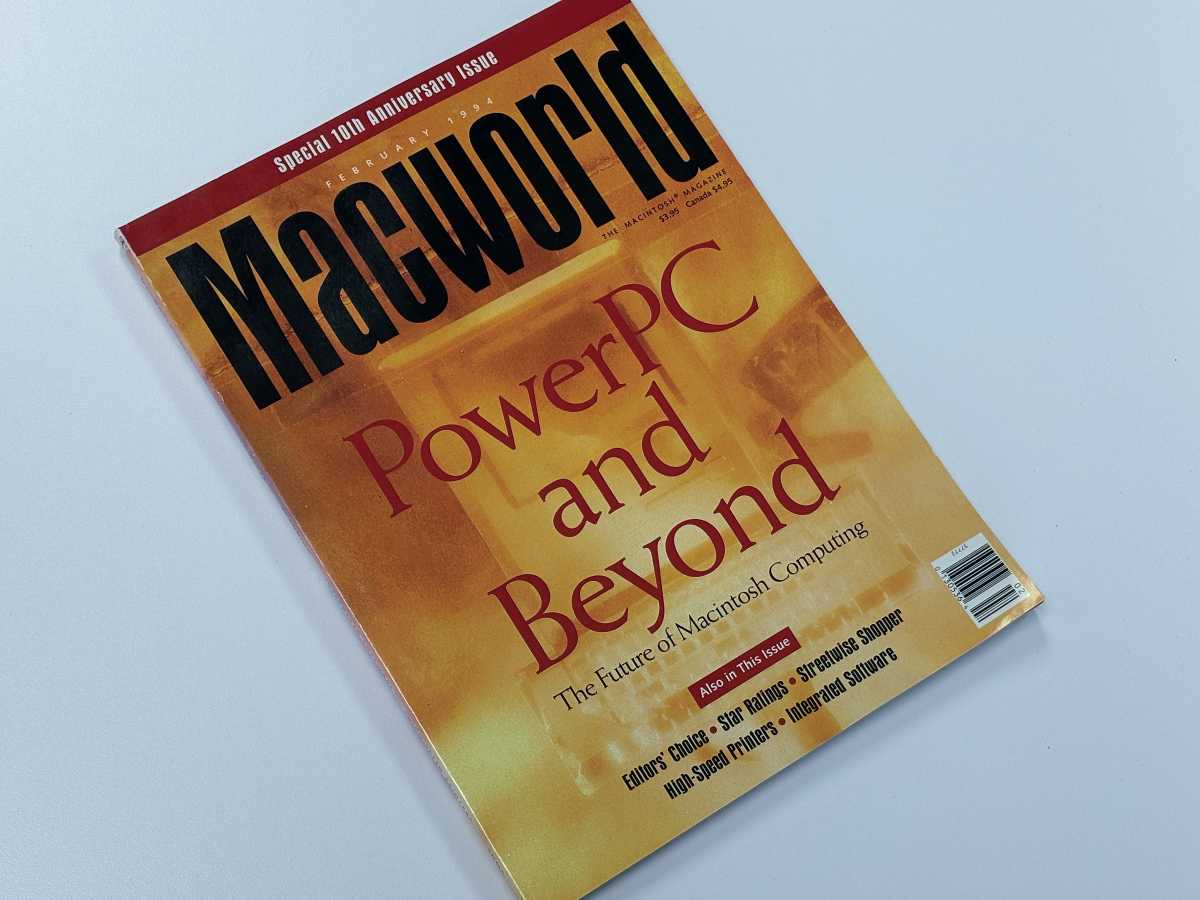

Macworld’s January / February 1994 issue detailed the first Apple chip from the Motorola 68000 transition to PowerPC.

Foundry

PowerPC was a new generation chip with features that differentiated her from the dominant intel processors of the time. The first Macs with PowerPC chips inside, nicknamed Power Mac (of course!), Arrived in March 1994. To reach this point, Apple did not only have to bring its software to a new conception of fleas; It had to allow compatibility with old Mac software.

Power Macs has executed a 68000 serial emulator that enabled them to execute non -native software at a slight speed penalty. My memory is that the Holy Microsoft Word Version 5.1, which was not native PowerPC but was great, was always quite usable (although significantly slower in certain tasks) on new fleas.

As a first transition with a user base who had engaged in the Mac during its first decade, it was a frightening period. For a year, we directed a column entitled “Ask Dr. Power Mac”, where users wrote to understand the technical challenges they could be confronted when they upgraded.

Apple’s biggest error at that time was that she did not control her developer tools. Metrowerks, a software company, finally bought by Motorola, built the Development Environment PowerPC Final, Codewarrior. (Apple would learn a key lesson in this; today, almost all of the development occurs in Apple’s own XCODE.)

In one year, the transition accelerated the speed, the new PowerPC native software shipped and Apple had a model for future processor transitions that the Mac may need. (But I hope no, right?)

Everything collapses

It is summer 2003, and as far as anyone knows it, the PowerPC era takes place. The new G5 processor (fifth generation) has been announced, and Steve Jobs promised that he would eventually reach a record record of all time. The community is delighted with the promise that this power also arrives on Mac laptops. During the East Coast Macworld Expo that year, Apple PRI proudly takes me on tour of the IBM flea plant in Fishkill, New York, where the cutting edge G5 will be produced.

It was a major turning point, but not in the way Apple wanted. IBM has never been able to produce this 3 GHz chip for Apple. The G5 was not suitable for laptops. And deep inside Apple, a SkunkWorks project ensured that the brand new Mac OS X could work on Intel processors. Twenty years ago, Jobs announced the change on stage of WWDC: the AIM Stock Exchange was cut and Apple would go from PowerPC to Intel.

This time, Apple gave the technology that translated the PowerPC code and executed it on Intel processors a name: Rosetta. The PowerPC software that he came has run more slowly, for of course, but the native native “universal” applications appeared quickly, and faster intel processors continued to appear at a rapid pace. The Mac had never been faster, and perhaps even more important, could no longer be negatively compared to the speed of Windows PCs.

This period was, in many ways, the most important decade in the history of the Mac. The growing success of the iPod (and later, the iPhone) put the Mac in front of people who may have ever considered buying one. A new generation of Windows emulators, capable of operating at full speed on Intel Hardware, has provided PC users withdraw which may need to run a handful of Windows programs. The Mac began to grow quickly.

Do it for themselves

It was good while it lasted, but 15 years after the start of the Intel era, Apple turned the page. Again, the company was frustrated by the pace of flea development and its lack of control over one of its platforms. But there was a key difference this time: Apple had, for a decade, conceived its chips for the iPhone and iPad. The developers created applications in Xcode who have compiled and executed on Apple processors.

It was, in many ways, the transition of the easiest fleas than Apple made. The tools were there. The developers knew Apple’s chips. Apple had years of experience to give him the confidence he could apply what he had learned in the process of building iPhone and iPad fleas to create powerful Mac variants.

The results were immediate: the Mac M1, when they arrived in the fall of 2020, were the best evaluated Macs in recent memory. They were so faster than their Intel predecessors than, in some cases, Rosetta 2, the latest version of Apple’s code translation layer layer, has executed Intel applications faster than they did on the original Intel material.

The boom in web and mobile platforms meant that Windows compatibility was not as important as in 2005. And in a fairly fun wrinkle, Microsoft had already started its own strange type of flea transition, creating a version of Windows which operated on processors very similar to those used by Apple. (He even has his own code translation layer. Obviously, Microsoft learned best.)

Which brings us to the last question: if Apple has changed its Mac chip architecture after 10, 11 and 15 years old, does that mean that the Apple Silicon era will also end?

Everything is possible, especially in the technology industry – but the big difference is that Apple now designs its own chips, its own specifications, in tandem with the products it builds. It is a huge advantage that he never had before.

Of course, Apple thought the same when he trained the AIM Alliance. And when he linked to Intel, who was the dominant chip manufacturer in the world at the start of this partnership but who had been supplanted by TSMC when he ended. Life arrives quickly. But, at least for the moment, the Mac lasts when the world and the chips change around it.