How her case differs from other missing persons : NPR

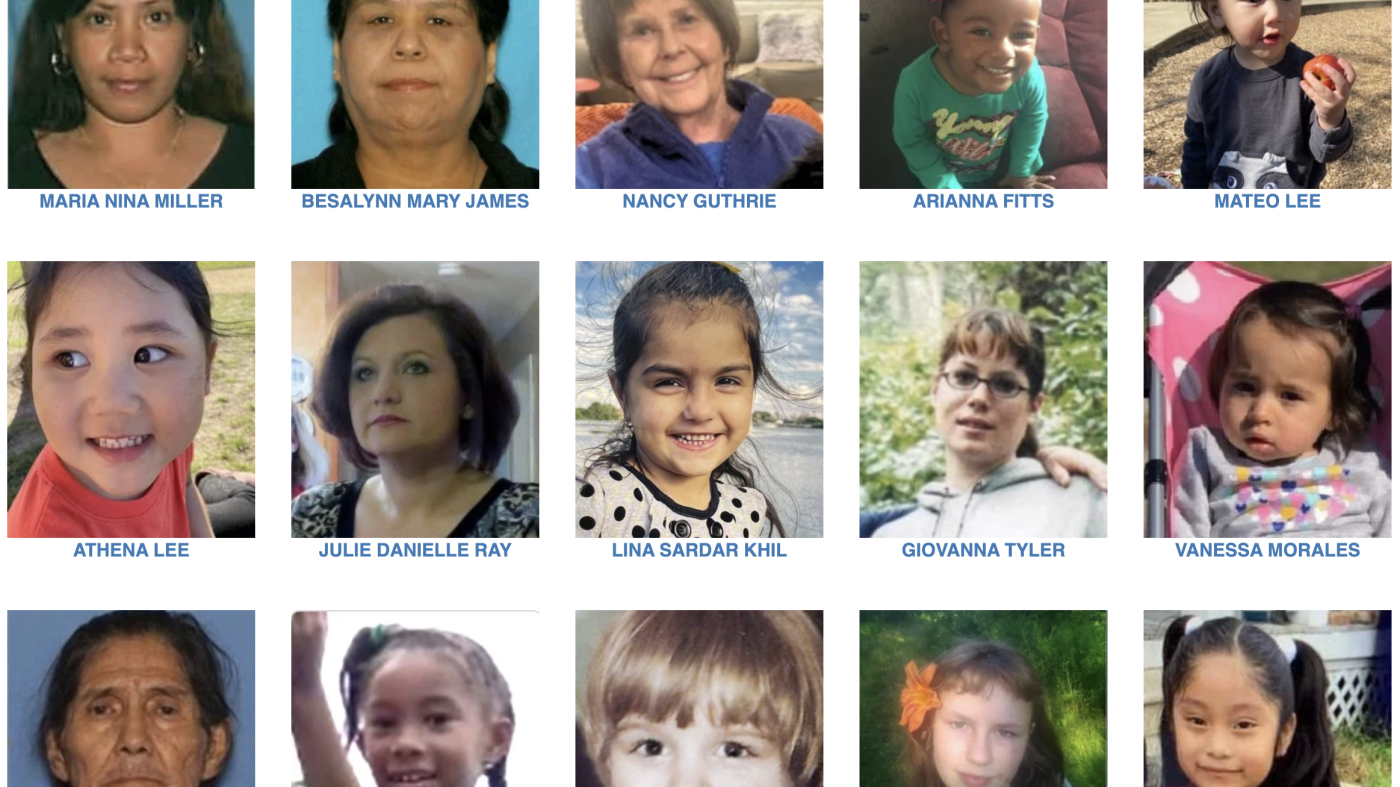

Nancy Guthrie’s case has received attention, in part because of the unique circumstances of her disappearance. She is seen here alongside others listed on the FBI’s kidnapping and missing persons page Thursday morning./FBI/ Screenshot by NPR

The kidnapping of Nancy Guthrie highlights the excruciating uncertainty experienced by thousands of families whose loved ones disappear each year. Experts see parallels with these cases, even though many details in Guthrie’s case are unique, from the victim’s age to his famous daughter, Today co-host of the show Savannah Guthrie.

The circumstances of Guthrie’s disappearance are “pretty shocking,” says Jesse Goliath, a forensic anthropologist at Mississippi State University.

“Usually we hear about smaller children, minors who disappear” and that attracts national press, Goliath said. “But having an older wife who disappeared and having [a daughter] that we see every day on TV” is extraordinary, he adds.

More than 500,000 people were reported missing in the United States last year, according to the Justice Department. But Tara Kennedy, media representative for the Doe Network, a volunteer group working to identify missing and unidentified people, says high-profile kidnappings are rare.

“I can’t remember the last time I heard about a ransom case outside of Guthrie,” says Kennedy, who has worked with Doe Network since 2014. “I always associate them with different periods of American history, like the Lindbergh kidnapping, and not someone’s mother in American history. Today to show.”

Kennedy and Goliath call the Guthrie case “strange.” Here’s a look at what it has in common with other missing persons cases and why it’s unusual:

“Unbelievable” key details

From June 2020 to June 2025, women made up more than 75% of victims in the approximately 240,000 kidnapping or kidnapping cases reported in the United States, according to FBI crime data. But of those, only 646 women were over 80, like Nancy Guthrie, who is 84, or less than 0.2% of all victims. Compare that to the age group that accounted for the largest number of victims that year: 20-29 year olds, who made up just under 30% of victims.

Other highly unusual revelations emerged as her disappearance persisted: from purported ransom notes sent to the media demanding millions of dollars to disturbing images of a masked gunman approaching Guthrie’s front door the night she disappeared.

Overall, it sounds like something out of a true detective novel, Goliath says: “It’s something unheard of.”

In missing persons cases, rapid response is crucial

Television shows have helped perpetuate the myth that families must wait 24 hours before reporting a loved one missing. But some shows and movies are right: the first 24 to 48 hours are essential to finding a missing person.

“Usually many of them will be [found] within 24 hours, especially in cases of minors and young adults,” says Goliath.

At this time, eyewitness reports might be more useful; sniffer dogs will have a fresher scent to follow; and surveillance videos and other electronic data are more likely to be intact and useful.

“The longer the person disappears, the more difficult it becomes” to find them, Kennedy said, citing decades-old unsolved cases.

Then there is the health of the victim. Whether the subject of a search operation wandered off and got lost, or was kidnapped or trafficked, Goliath notes that after 48 hours, their well-being could be compromised — by the elements or by health issues such as Nancy Guthrie’s pacemaker and her need for daily medication.

“Unfortunately, if that person is not found within the first two days, their chances of survival decrease exponentially,” says Goliath.

Who are the missing people in the United States?

At any given time, approximately 100,000 people are missing in the United States, according to Goliath and Kennedy. At the end of 2024, for example, the National Crime Information Center recorded more than 93,000 active missing persons cases in the United States, while a total of 533,936 cases were recorded in the federal tracking system that year.

Of those cases, more than 60 percent — or about 330,000 — involved minors, according to the NCIC database, which law enforcement uses to share criminal arrest warrants, missing persons alerts and other records.

Among those missing, Goliath says there is an “overrepresentation of missing Black and Indigenous populations, particularly women, across the United States.”

In Mississippi, he adds, “our highest demographic of missing [persons] they are young black women.

Black Americans are also overrepresented in kidnappings. While members of the group make up less than 15 percent of the U.S. population, they account for more than 25 percent of reported kidnapping or kidnapping victims, according to FBI data.

But a large number of missing persons cases also go unreported because certain communities, such as people of color or those without official status in the United States, are less likely to come forward to authorities. And Goliath notes that indigenous people living on reservations might have limited access to law enforcement.

Another dynamic that skews public perception, Kennedy says, is “missing white woman syndrome,” when the national media becomes obsessed with a missing white woman.

“As someone who researches cold cases in terms of finding information, the disparity of information available, cases involving people of color, is ridiculous,” she says.

Call to action and simpler ways to share data

Goliath says every missing person case, not just Guthrie’s, needs to be widely publicized and shared, to increase the chances of bringing someone home.

“We call it a silent crisis,” he says, “that there are missing people in the United States, all over the country, who don’t really have the same representation on social media or national media representation for their case.”

It is also difficult to find standardized data on missing persons, due to the diversity of rules and resources. Law enforcement agencies across the country are only required to report missing persons cases to the federal government if they involve minors, for example.

In addition to NCIC, missing persons data is collected by NamUs (the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System), which provides public access. But currently, only 16 states require mandatory reporting to the NamUs Clearinghouse for missing persons cases.

Goliath says he would like to see a national project lobby for more states to adopt NamUs requirements. As NPR reported last year, a large share of U.S. police departments were not listed in the system.

“It would be useful, because it’s already a system that exists,” Goliath says. “Law enforcement already does it. So let’s make it so all states can use NamUs.”