45-hour voyage in replica canoe tests Paleolithic migration theory

Credit:

Kaifu et al., 2025/CC-By-ND

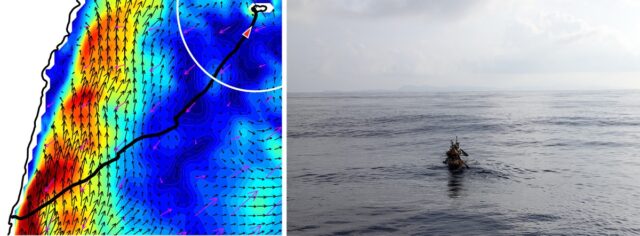

At the 30-hour mark, the captain ordered the entire crew to rest, letting the dugout drift freely for a while, which fortunately brought them closer to Yonaguni Island. At hour 40, the island’s silhouette was visible, and over the next five hours, the crew was able to navigate the strong tidal flow along the coast until they reached their landing site: Nama Beach. So the experimental voyage was a success, augmented by the numerical simulations to demonstrate that the boat could make similar voyages from different departure points across both modern and late-Pleistocene oceans.

Granted, it was not possible to recreate Paleolithic conditions perfectly on a modern ocean. The crew first spotted the island because of its artificial lights, although by that time, they were on track navigationally. They were also accompanied by escort ships to ensure the crew’s safety, supplying fresh water twice during the voyage. But the escort ships did not aid with navigation or the dugout captain’s decision-making, and the authors believe that any effects were likely minimal. The biggest difference was the paddlers’ basic modern knowledge of local geography, which helped them develop a navigation plan—an unavoidable anachronism, although the crew did not rely on compasses, GPS, or watches during the voyage.

“Scientists try to reconstruct the processes of past human migrations, but it is often difficult to examine how challenging they really were,” said Kaifu. “One important message from the whole project was that our Paleolithic ancestors were real challengers. Like us today, they had to undertake strategic challenges to advance. For example, the ancient Polynesian people had no maps, but they could travel almost the entire Pacific. There are a variety of signs on the ocean to know the right direction, such as visible land masses, heavenly bodies, swells, and winds. We learned parts of such techniques ourselves along the way.”

“Traversing the Kuroshio: Paleolithic migration across one of the world’s strongest ocean currents,” Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv5508 (About DOIs).

“Palaeolithic seafaring in East Asia: an experimental test of the dugout canoe hypothesis,” Science Advances, 2025. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv5507