The App That Asks You To Report Illegal Immigrants For Crypto

A new app dares to pose a question that nobody has thought to ask: what happens when you combine right-wing fervor over hunting down undocumented immigrants, cryptocurrency speculation, and Proud Boys leader Enrique Tarrio?

It’s called ICERaid, and the idea behind it is either ingeniously simple in its pitch for civic engagement or nauseating in its wicked opportunism, depending on your bent: the app offers users tokens of the $RAID digital currency in exchange for taking pictures of undocumented immigrants and submitting them to the app. ICERaid claims that it will then provide the photos to law enforcement, supposedly incentivizing users to contribute to the MAGA project of rooting out undocumented immigrants while watching the coins they receive spike in value.

Like many other projects in cryptocurrency, the point is at least partly to attract attention — either through riding off news topics or by creating an app weird and sinister enough to generate explosively negative headlines — thereby drawing in more users.

That’s not unusual for novel crypto coins. They’re speculative assets that often thrive on persuading large numbers of people to buy in. It’s why figures including the Trumps and Elon Musk can so easily gain such a powerful footing in the space: they generate gargantuan amounts of attention.

What makes ICERaid different is that it combines the desire to see the value number go up that’s core to the appeal of so many crypto projects with Stalin-style denunciations. In this case, the pitch is that reporting an undocumented immigrant could earn you cash. It’s the speculative rush around crypto combined with the fundamental authoritarian impulse: bringing your neighbors into line and getting the state to act against them.

The more people that ICERaid users report, the more cryptocurrency they receive in return, should the app validate the targets. There’s a fixed number of coins that the company has issued; as reports come in to ICERaid and are validated, demand increases, in theoretically raising the price. In the world of ICERaid, this is all part of a vision called “GovFi”: instead of the state providing a service, like law enforcement, it will devolve to citizens incentivized to participate through crypto. Think quasi-organized vigilantism, on the blockchain. Earlier this month, Enrique Tarrio, the Proud Boys leader, said that he had signed on as “czar” for the project.

The idea has been promoted over the past several months by a man named Jason M. Meyers, a former stockbrocker who has spent the past several years working on various cryptocurrency projects. One Securities and Exchange Commission document suggests that he even met with SEC officials this month for one initiative.

Meyers brought a complicated past to ICERaid. In 2014, he consented to a ban from the financial services industry in a letter agreement with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). Meyers neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing in the letter, which detailed allegations that he misappropriated at least $700,000 from investors. TPM asked Meyers about the allegations, and why people should trust him with their money via the crypto venture.

“They’re not trusting me, they’re trusting Enrique,” Meyers replied.

How They Tout It

Meyers told TPM during a phone interview earlier this month that he came up with the idea for ICERaid after having “suffered from immigration fraud.” He declined to specify what that meant, saying that “it’s something I’d like to forget.”

Answering the question of someone’s legal residency status can be extremely complicated, and requires access to government databases and knowledge of visa and other status arrangements that have shifted week-by-week under the Trump administration.

ICERaid casts itself as using AI as a kind of deus ex machina to allow everyday citizens to solve that problem. AI, Meyers told TPM, then performs “validations” of photos that users submit. He declined to specify how that worked. ICERaid plans to make the data it collects available to law enforcement, Meyers added.

The app holds space for reporting other forms of wrongdoing that carry vaguely political connotations, not only immigration. As Tarrio put it on a podcast appearance this month, ICERaid “allows you to report illegal immigrants and other crimes, obstruction, assaults on the police officers, looting, rioting, and things like that.”

ICERaid has gone even further in exploring “use cases” where people can cash in through denunciations. On Instagram, ICERaid invited users to report liberal judges in controversial cases, singling out Chief D.C. Judge James Boasberg for his handling of the administration’s removals under the Alien Enemies Act and suggesting he was a candidate to be reported for “terrorism” or “obstruction.”

The app requires users to take photos of suspects. ICERaid advised users in an Instagram video to go to federal court in a “blue state” and “secretly snap a photo of the judge. Don’t let the bailiff see you.”

Marketing this requires a certain deranged finesse: being as wanton as possible in promotion, while also making sure to tie it to the news of the day. In response to a post from ICERaid’s X account about NYC comptroller Brad Lander being detained by ICE, Tarrio wrote of ICERaid: “this is what it’s built for.”

It’s unclear how the app works to “validate” any of this. Per Meyers, the app’s validation procedure works as a filter: not just any photo of a suspected undocumented immigrant, liberal judge, or NYC mayoral candidate will do. It has to pass an ICERaid in-app test. This system will, according to a post on the app’s website, be ready later in the summer: “evidence validator deployment” is scheduled for August, it says.

Meyers told TPM that users have to submit photos tagged to the location at which they were taken. Once the app verifies the location that the photo was taken, it then “profiles the suspect” and “gauges sentiment.”

TPM pressed Meyers about how any of this is supposed to work. “I’m not on the tech side, I can’t articulate it to you,” he said.

The Difference Between Fancy Jeans and $RAID

Focusing on the ins and outs of how the app “profiles suspects” raises a host of privacy concerns. But it also partly misses the point. As Tarrio said in a June 11 episode of his Lords of War podcast alongside another Proud Boy member, the purpose is growth. In his words, he wants $RAID, the cryptocurrency earned by users of the app, to “become as big as, uh, as the Federal Reserve.”

On the same podcast, the co-host, Barry Ramey, compared the app to Pokémon Go: “Basically this is like the conservative version of that Pokémon game that came out years ago.”

Meyers described Tarrio’s role in similar terms, saying that he can effectively raise awareness and that the app “fits with his ideals.”

“He has the network of people that would use it,” Meyers said. “He has the following.” TPM asked if Meyers had the Proud Boys in mind when referring to Tarrio’s “network”; Meyers said he did not. Tarrio did not reply to request for comment from TPM.

But the basic reality is that growing the user base will increase the value of the coin. As of this writing, the value is relatively small: one $RAID token goes for $0.0009157. When TPM asked if Tarrio and Meyers hold the token, ICERaid replied that tokens are “allocated across all team members, key opinion leaders and campaign contributions, all of which is subject to equal daily vesting until January 19, 2029.”

A coin with a very low price and audacious plans to attract attention is consistent with how many memecoins operate, Omid Malekan, a professor at Columbia Business School who teaches a class on Blockchain, told TPM.

Malekan is a supporter of the crypto industry, but has been an outspoken critic of memecoins. What marks them out from the rest of the industry, Malekan said, is the lack of pretense to any kind of utility.

“Unless you figure out a way to create some kind of a lasting source of value for the token, the whole thing’s gonna fall apart, and it is just a memecoin,” Malekan said. “And to me, memecoins are effectively just pumps and dumps.”

He added that memecoins are often focused on generating massive amounts of public awareness out of a belief that “the attention is, in and of itself, a valuable thing.” There’s a whole ecosystem here: some memecoins exist entirely on the popularity of an associated phrase: Let’s Go Brandon, the anti-Joe Biden slogan, picked up a memecoin of the same name. But other species of memecoin can have associated apps, Malekan said, which propose a veneer of utility.

“They’ll say, ‘well, the utility is the app,’ but no. You’re putting the cart before the horse — people get the app because they want to get more of the coin,” Malekan said.

ICERaid’s model holds out the prospect of crypto riches in exchange for using the app to report people. ICERaid has denied that it’s a memecoin, describing itself as “a #web3 app that enables citizens to crowdsource and verify 8 categories of criminal evidence.”

Still, the community around the app is intently focused on causing a dramatic rise in the value of $RAID.

TPM reviewed chats from a Telegram group named after ICERaid and focused on discussing the coin. One user, JSON Meyers, features a profile picture that Meyers has used elsewhere on the internet, and appears to speak for the app in the chats. The account is linked to posts promoting other ventures in which Meyers is involved.

Last month, the Meyers account and others began discussing a purchase of nearly 50,000 units of $RAID. The Meyers account celebrated with a “WOOT WOOT!!!” before advising users that they should buy more of the coin once it is released — ”ONLY when it hits $1B cap.”

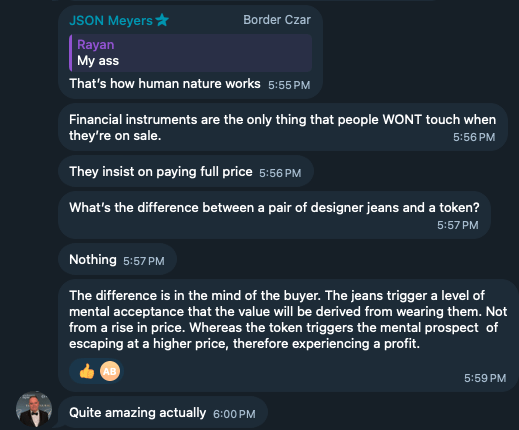

After another Telegram user replied dismissively with “my ass,” the Meyers account, which describes itself as “border czar,” shot back: “That’s how human nature works.”

The account then posed a rhetorical question: “What’s the difference between a pair of designer jeans and a token?”

“Nothing,” the Meyers account wrote.

“The difference is in the mind of the buyer. The jeans trigger a level of mental acceptance that the value will be derived from wearing them. Not from a rise in price. Whereas the token triggers the mental prospect of escaping at a higher price, therefore experiencing a profit.”

Pulling the Thread

The exact nature of Meyers’s ties to ICERaid and whether he has any formal role are unclear.

During an early June interview with TPM, Meyers said that he was promoting ICERaid, and discussed having created it at one point. TPM could not identify any corporate records that reflect ICERaid’s existence. ICERaid’s website domain registration is mostly obscured, apart from saying that its registrant is based in Zug, Switzerland. In podcast interviews, Meyers has been introduced as the “creator” of ICERaid.

But like much of the rest of ICERaid’s structure, the responses that the company and people associated with it gave to TPM were murky. This week, Meyers directed TPM via text to an ICERaid email address for “media.”

A response from the email address disavowed any affiliation with Meyers: “Jason currently has no official role with ICERAID. It was announced that Enrique took over the role as ICERaid Czar.” The email also asked TPM to make clear that while there are many cryptotokens called “Raid,” theirs is different. Per the address that ICERaid provided, there are 150 holders of the token as of this writing.

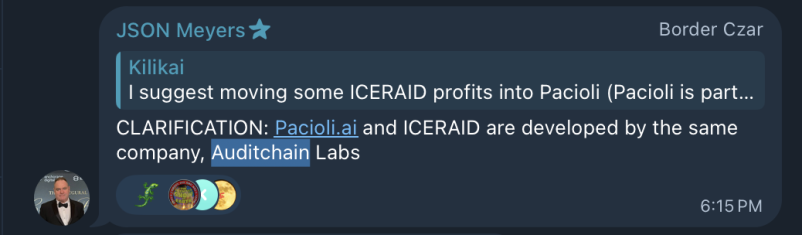

TPM was able to establish some evidence of a link between Meyers and another cryptocurrency firm: Auditchain Labs AG, based in Zug, Switzerland. That company describes Meyers on its website as “lead architect” and says that he’s the developer of another crypto project called Pacioli.ai.

A review of Auditchain Labs AG’s Swiss corporate records did not show any mention of Meyers. He does appear in the records of another Zug-based company called “Auditchain GMBH in Liquidation.”

Swiss corporate records list Meyers as a member of Auditchain GMBH in Liquidation’s executive board, and say that he has signing authority. A Delaware LLC called Auditchain USA Inc. is also listed as a member of the company. TPM reviewed a federal lawsuit in which Meyers said that he had served as an interim CEO of Auditchain USA Inc.

If you keep pulling these threads, it can feel like they each lead towards a thousand other spools of string. Take Pacioli.ai, the crypto project for which Meyers is described as the “lead architect.” An SEC document records Meyers as having met with the Trump administration’s Crypto Task Force on June 2. Per the document, the group discussed Pacioli’s potential use in “externally validat[ing]” corporate financial disclosures.

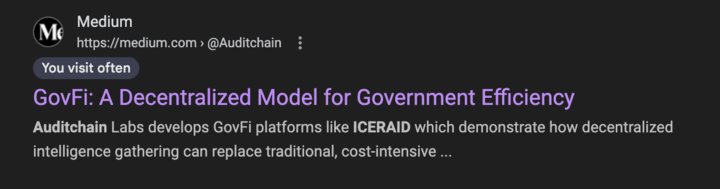

There’s yet another lead: searching “Auditchain” and “ICERaid” on Google leads to a result with a cached summary that claims Auditchain develops ICERaid. Clicking through to the current version of the page leads to a Medium post that makes no such claim.

In March, the Meyers account wrote that Auditchain Labs developed ICERaid in the Telegram chat.

But to TPM, Meyers texted: “Auditchain and ICERaid are not affiliated.”

When TPM followed up on the question at ICERaid’s “media” email address, the response was the same: “There is no affiliation with Auditchain.”

The experience of reviewing all of this starts to resemble watching a shell game. It’s slippery. Is Meyers really a creator? What does that even mean when it comes to an app or token? It’s unclear.

The FINRA letter, signed in 2014, says that Meyers misappropriated more than $700,000 in investor funds. He never told investors that at least some of the funds would go to “personal medical expenses, cash withdrawals, payments to a charity for which Meyers was a board member, international travel, concert and movie tickets,” per the document. Meyers, the document said, agreed to be barred from the financial services industry — I.e, working with any FINRA member firm — per the agreement, without admitting or denying any wrongdoing.

Meyers gave an elaborate account during his initial phone interview with TPM in which he was the true victim in all of this. FINRA was, he said, a “captured regulator” hell-bent on getting a win, facts or no.

“They’re not a government agency,” Meyers noted. “In fact they are a constitutional bypass.”

“The reason that I gave up is because they drained every penny that I had. I didn’t have the money to fight them,” he said. “It happens to tens of thousands of people that don’t do anything wrong.” Agreeing to sign the deal was better than wasting money on legal defense.

Meyers told TPM that after the FINRA ban, he left the financial services industry and found a new career in cryptocurrency. He recounted meeting fascinating people in the experience, and emphasized to TPM that “each one of them are of the opinion that just because you want privacy doesn’t make you guilty of anything. And cryptography is about protecting information in the presence of adversaries.”

I spoke with former FINRA employees about Meyers’ case. One, an ex-FINRA enforcement counsel named Gary Carleton, pointed out that Meyers, though he did not agree with or deny allegations of wrongdoing, had made the choice to sign an agreement in which he was barred.

Carleton told TPM that “people do make allegations against brokers,” but that “well under half of those that are brought forward actually result in any kind of disciplinary proceeding.”

The process then goes through a few checks, Carleton said: a non-enforcement body within FINRA reviews cases before they’re brought. Everyone has a chance to appeal to the SEC, should they wish.

Another former FINRA official, who wished to remain anonymous, said Meyers was telling a familiar story.

“They all say, ‘oh, I was forced to settle.’ They all say it was a vendetta,” the person said. “But usually, if you’re a captured regulator, it works the other way. If you’re a captured regulator, the idea is you’d go out of your way to protect the industry, not to ban people from it.”