In Boston and beyond, Tibetans in exile keep their culture alive

At Harvard Square, the national flag of Tibet, with its golden yellow sun and its red and blue streaks, swells in the wind while the organizers distribute brochures on Chinese oppression of Tibet. A dozen other generations of various generations are held nearby in the silent monitoring.

The Boston Tibetans have gathered here in Cambridge every week since 2008 to express their solidarity with those inside Tibet, who are confronted with the systemic repression of their language, their culture and their history. There were days when Dhondup Phunkhang, a Tibetan who immigrated to Boston over 20 years ago, would be the only person with these Wednesday white demonstrations. He held the day before in the rain, snow and heat.

“It was almost like a meditative practice,” said Philkhang. “It solidified my resolution for my belief and my people.”

Why we wrote this

A story focused on

The small tibetan community tight of Boston is a microcosm of Tibetans living in exile in the world – communities that have favored a feeling of cultural resilience through generations.

Even if the movement of “free Tibet” has largely disappeared from the dominant public conscience, the Tibetans continued to line up in India, America and beyond. Welded communities like that of Boston – which went from 50 people in the early 1990s to more than 700 people today – are cultural resilience centers. The ancients go from Tibetan Buddhist teachings and traditions to the young generations who have never set foot in their homeland in Western China. This culture was fully exposed this week when cities around the world celebrated the birthday of Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet in exile.

“All over the world, from Toronto to New York to Dharamshala via Tibet, shows that Tibetans have adopted their culture and identity so strongly,” said Lobsang Sangay, member of the Harvard Law School and former president of the government of Tibet in exile. “It’s not like a linear regression, you know? So, the first generation has a strong identity, the second generation becomes weak, and the third generation loses it. … In fact, ours is the opposite.”

Exile nation

The 1950s marked a decade of upheavals for Tibet. The Chinese Communist Party sought to annex the set rich in resources, which would help secure the southwest border of the country. But when Chinese tanks entered Tibet in October 1950, local leaders fought to keep their autonomy.

Tensions reached a head during an uprising from 1959, in which the 23 -year -old Dalai Lama fled to neighboring India, establishing a government in exile in the northern city of Dharamshala. More than 80,000 Tibetan refugees followed him.

At the time, many hoped for a rapid return to their homeland, but it never happened. Today, more than 6 million Tibetans still live in China are faced with that certain diaspora and scholars describe as a “worse than ever” repression. Tibetans must replace the images of Buddhist religious teachers with Chinese political leaders. Children are forcibly separated from parents to register for statements managed by the state, and the Tibetan national anthem is prohibited.

Beyond the Chinese borders, the Dalai Lama has become a symbol of the non-violent Tibetan resistance and a champion of world peace and compassion. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, helping to transform Tibetan independence into a causality in the west and open the door to the first wave of mass migration in the United States.

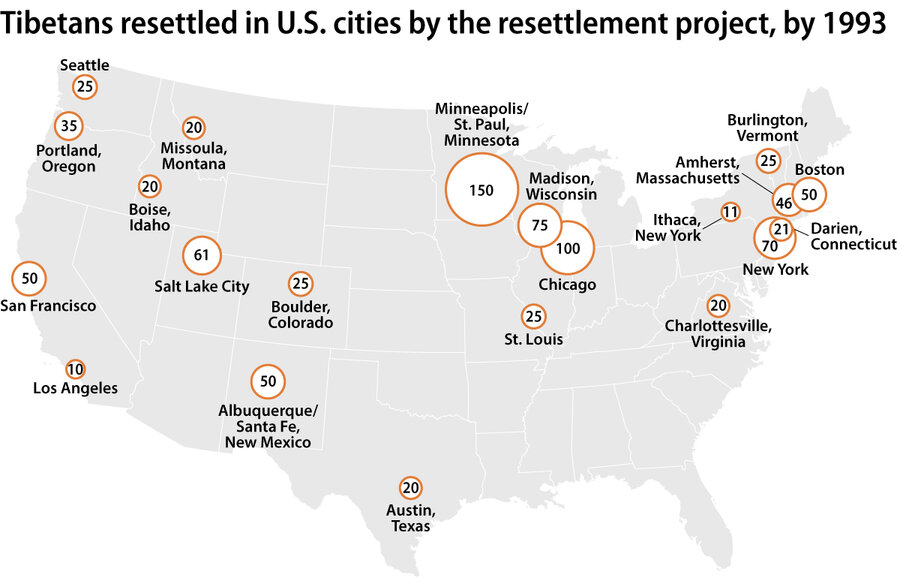

Sangay remembers how, in the early 1990s, the government of Tibet selected 1,000 people to disperse on 21 “cluster sites” in the United States as part of the Tibetan United States resettlement project. The Dalai Lama gave everyone a small statue of the Buddha.

“You are the Tibet ambassador,” said Sangai, the Dalai Lama told volunteers, who were chosen by a lottery system. “You are going to the west, it’s a crucible, but don’t lose your Tibetan identity. Make your best to preserve Tibetan language, culture and spirituality. ”

Of nearly 150,000 Tibetans living in exile today, around 26,000 residents in the United States, according to the Central Tibetan administration, the Government of Tibet in exile. Many Tibetan Americans live in these original resettlement sites, including Boston, where the commitment to preserve Tibetan culture is still strong.

Reasons to celebrate

While the bells of the church sound outside the Greek Greek church of the Archangels in Watertown, Massachusetts on Sunday, the celebrations inside the room rented by the Tibetan community of Boston are well in progress.

Women wear turquoise jewelry reserved for special occasions, and families drape white Khatas, a ceremonial scarf, around a portrait of Dalai Lama. Above, a fabric tapestry representing the Potala Palace – the traditional Dalai Lamas House in Tibet – flocks in air conditioning.

“It is literally our sun, our moon and our moral compass,” explains Tenzin Kunsang, an event organizer. “We are so proud of him, so proud to be Tibetans.”

There were several reasons to celebrate.

Last week, just before its 90th birthday, the Dalai Lama approached the growing uncertainty of its succession plans. In a recorded video and a written declaration, he said that the institution of the Dalai Lama will continue, dissipating the speculations according to which he would be the last to occupy the role in the midst of a Chinese interference.

In 1995, when the Dalai Lama identified a young boy in Tibet like the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama – an important figure in Tibetan Buddhism which helps to identify the next Dalai Lama – China quickly distant the boy. His fate is still unknown, and Beijing has installed his own Lama Panchen in his place. When the time comes, many expect the Chinese government to choose its own Dalai Lama.

“What really happens is [the Dalai Lama] Recalls to China that his authority and that of his successor comes from a advisory process, “explains Robbie Barnett, professor at the school of oriental and African studies which focuses on the history of modern Tibet.” It is a legitimacy with which China cannot compete – it is the subtext here. “

The message has left many Tibetans to feel “relieved”, explains Ms. Kunsang. “No country, no government, no group should interfere in this sacred process. We have heard this strong and clear.”

As the Tibetan diaspora is growing, it is possible that the next Dalai Lama was born outside of Tibet – in India, or a city like Boston. Indeed, in his recent memories, “Voice for the Voiceless”, the Dalai Lama declares that his reincarnation is in “The Free World”.

But it is far from the spirit of the Tibetans who gathered around large banquet tables in Watertown. Jampa Ghapontsang, one of the first Tibetans to go from Dharamshala to Boston, is simply happy to see Tibetan culture prosper on the other side of the world.

“We are in our third generation of Tibetans, and I just see growth,” she says, while schoolchildren swirl in the traditional music room. “For me, it’s a dream.”