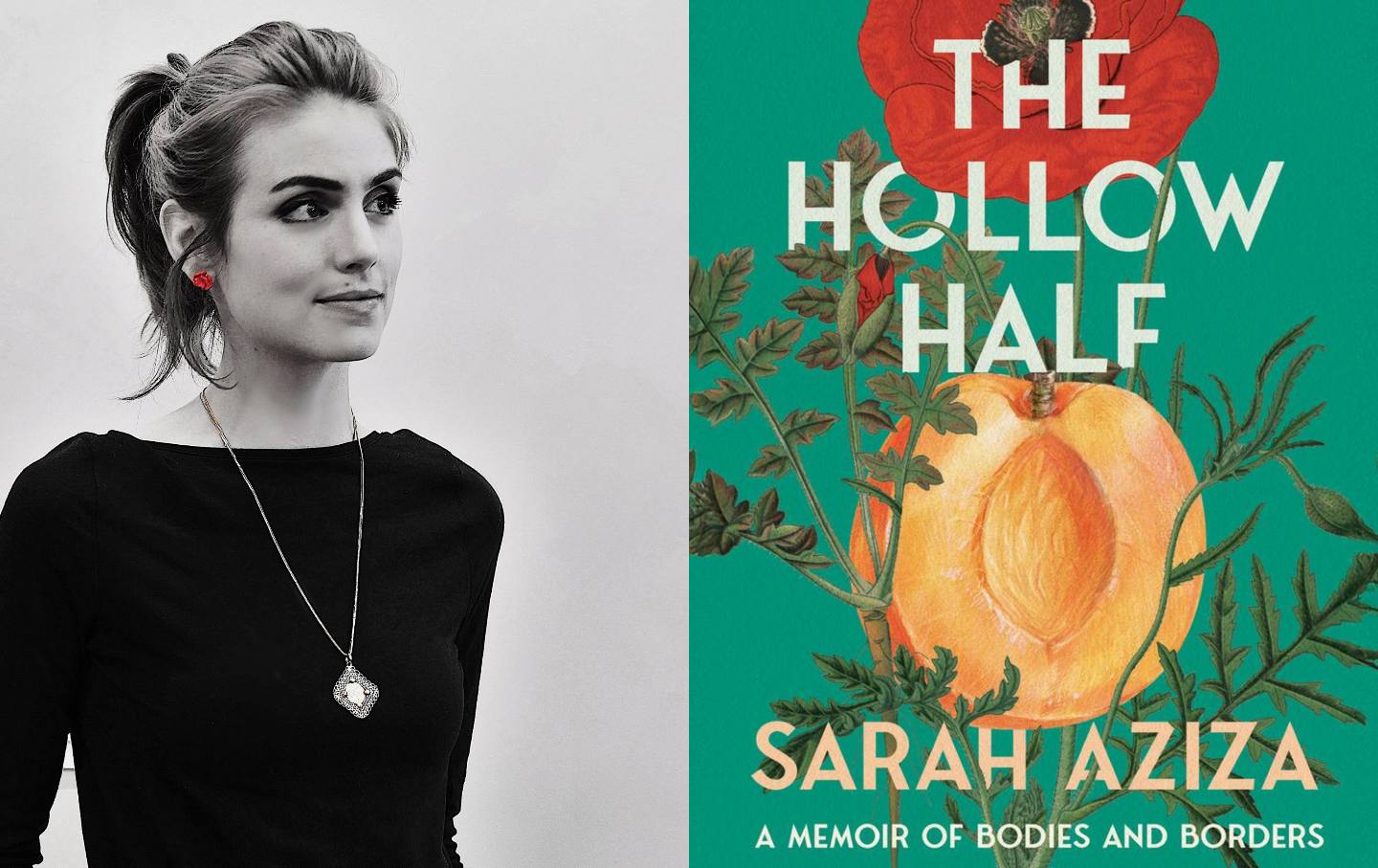

Living With Fracture: A Conversation With Sarah Aziza

Society

/

StudentNation

/

June 26, 2025

The Hollow Half is not simply a memoir of personal recovery or an account of Palestinian political history. It’s an exploration of fragmentation.

Stories about displacement and diaspora often broach familiar themes: straddling two worlds, overcoming rupture, stitching the self back together across the chasm of languages and borders. Sarah Aziza’s debut book, The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders, offers a striking alternative to this pattern.

The memoir chronicles Aziza’s life-threatening struggle with anorexia and its entanglement with intergenerational trauma and the Palestinian history of dispossession, exile, and erasure. As she confronts her eating disorder, Aziza becomes a student of her lineage. Lessons from her grandmother, a refugee from Gaza, and the Palestinian legacy of love and sumud—steadfastness—offer the keys to resisting the disease in herself and the global maladies of colonization, patriarchy, and marginalization.

But The Hollow Half is not simply a memoir of personal recovery or an account of political history. It’s an exploration of fracture. Aziza moves between places (Palestine, America, Saudi Arabia, Jordan), between identities (descendant, partner, survivor), and between languages (Arabic and English) without necessarily seeking closure. Instead, she invites the reader to linger in the unresolved, where yearning for a lost past becomes a transgressive act and fragmentation a tool against complacency.

By sitting with rupture rather than searching to mend it, The Hollow Half becomes a genre-defying reflection on inherited wounds, imposed silence, and the liberating truths stored within the corporeal realm. In lyrical and incisive prose, Aziza examines how the legacies of conquest and expulsion reverberate through the most intimate of terrains: memory, language, and flesh. Steered by the specter of her Palestinian grandmother, she crafts a reckoning with the past and present that renders the book both timely and timeless.

The Nation spoke with Aziza about The Hollow Half on May 30 at the 2025 Puffin Nation Fund Student Journalism Conference. This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

—Lara-Nour Walton

Lara-Nour Walton: You open your book with the quote, “For Gaza Words Fail.” You have also published essays—“Crimes Against Language” for The Baffler comes to mind—where you discuss how the ongoing genocide makes words “incomprehensible.” What was the impetus for writing this book, and how did your ability to articulate yourself change with the onset of the genocide?

Current Issue

Sarah Aziza: It was a journey. I passed through multiple stages of world events while writing this book. I started writing in early 2020—so under the pall of the early pandemic. It was a very disorienting time. It was also when I had recently emerged from the hospital after being admitted for a near-fatal eating disorder. I felt really dismantled as a human being, and I started to feel this hunger to revive my memories of my grandmother. I had begun dreaming about her, and, as a writer, I was processing that through words. I was putting things down in a Google Doc that was growing and growing, and eventually, my investigative side clicked into gear, and I started doing a lot of research, oral history, building these stories, and starting to, unintentionally at first, connect them to my own personal story, my own personal struggles.

I had about two-thirds of it written by October 7, 2023. I had struggled with finding language for many things throughout the process, but it was just a completely new level of horror and shock as events unfolded in Gaza. I was recently in conversation with Omar El Akkad, who is a fantastic Egyptian writer and journalist, and he asked me if writing matters. I told him I ask myself that every day, and I certainly ask myself that every day during the genocide.

The biggest thing that changed after October 7 was that I wanted to become fiercer as far as the end of the book goes. I changed the ending completely. Each chapter is named after a concept in Arabic. And I changed the last chapter to “مقاومة” which means resistance. I wanted to end with something that went all the way politically—that didn’t only recount family and personal stories and leave it at that. I wanted the reader to have no doubt about the political and material conditions that cause these personal stories and to indict and convict Anglophone readers especially. If you’re reading in English, you’re probably complicit in some way and have to work very hard against that complicity. Just by virtue of where we are—the United States, Canada, the UK—English is usually a violent context.

LNW: In your book you talk about your time in an anorexia treatment center, which you were admitted to in 2019. You wrote: “I accepted that I would not heal inside those walls. The staff, which worked deftly to restore my flesh, could not see what stalked my blood.” Can you explain what exactly stalked your blood? Why did it manifest itself in anorexia and why was the Western mental health framework incapable of helping you recover?

SA: I mentioned being dismantled as a human being after I spent four months in that institution, and it was a really punitive carceral experience where we were just controlled. This psycho-medical industrial model just compounded what I’d always heard in the West, which is not just anorexia, but depression, anxiety, all of these things that so many people suffer from, are apolitical and individual. So I was told many times that I had no reason to be so sick, and I really took that to heart—that I’m just crazy, and it’s a very unhelpful framework and also very untrue.

I always felt crazy for being told that I should be well in the world that we live in; there’s so much that’s sick about our current society, and I was a very politically minded person. I was an activist, but I didn’t give myself permission to create political connections with my eating disorder. There’s a lot of shame involved too, which lends itself to self-blame. The book’s structure is very unorthodox because I started to see how multiple temporalities and geographies are present simultaneously.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

We don’t have to be genetic scientists to sense the fact that our history and our family’s history are embedded in the everyday. I just started to see echoes and eventually gave myself more and more permission to trust those echoes and continue to uncover very uncanny parallels between my grandmother, my father, and my own life that eventually just made it feel inevitable to me that I would expand the lens of this illness into something much more psychosocial and political.

It’s very hard to be a Palestinian and be well in the middle of a genocide. It’s very hard to be a person of conscience and be well. It’s a malignant system that we live in, and trying to be well is a communal project. We must focus on dismantling the things that are refusing health for so many of us.

LNW: In your book, you make stylistic choices that defy genre and convention. At times, you sprinkle untranslated Arabic words or phrases into the text. Elsewhere you censor the pet name that your husband calls you or refer to people only by the first initial of their name. What is the significance of these omissions? How do they challenge expectations in memoir writing and in Western literature more broadly?

SA: I thought a lot about opacity and legibility while writing this book. As someone who’s Palestinian but the daughter of a Palestinian father who modeled assimilation as someone who could be white-passing, as someone who speaks English as their first language, I only knew how to exist in the world as someone who was a code switcher, shapeshifter, always trying to accommodate the American Anglophone reader or context that I was in. I disappeared inside of a lot of those concessions. I knew somewhat who I was, but that was secondary to accommodating the context in which I found myself. In this book, I tried to come closer to reflecting reality as I experienced it. It is very hybrid and multilingual and contains privacies that I decided to maintain for myself.

In memoirs—especially those written by non-white women or in the recovery genre—there’s often a voyeuristic expectation that you’re just gonna dump everything on the page and that readers deserve access to everything. I wanted to challenge the reader in multiple ways, in one way, reminding them that I am not just bearing my unedited and uncrafted experiences, but I’m making choices because this book is conceptual. I block out certain things to remind the reader, “Hey, I made a choice, and this is private.” Or “Hey, the best way to express this is in Arabic.” It’s a good reminder that people who speak a different mother tongue are always editing, translating, and making themselves legible. If you’re reading this book in the United States or Canada, which are the two countries it’s released in right now, you’re probably being accommodated to all the time. So maybe that’s a moment of an examination for an Anglophone reader. And for Arabic readers, it’s a reminder that they’re actually being thought of as my first audience.

LNW: Your book is deeply researched—footnotes ground the reader in facts about eating disorders and Palestinian history. But what struck me most was your command of your family history, which is depicted with such vivid detail. How did you go about documenting your family’s past? Did you consult archives? I know you spoke with your father about your grandmother’s life, but how did you so evocatively recover memories that he was not even alive to witness?

SA: I was trained as a journalist, so I initially thought the only material I could work with was what I could literally footnote or extract from the archive. But the truth is bigger than the facts. There are things that are true, that are not documented as fact. Facts are authorized, often by powers that don’t prioritize lives like my grandmother, who’s a disabled woman from Gaza.

So, my book was a collection of oral histories. It was an examination and an exhaustion. I exhausted the archive, but then I took a step further. The theorist Saidiya Hartman gives us this concept of critical fabulation, which is imagining with and into the silences of the archive. I think there’s a way of honoring and getting closer to certain truths that involve narrative. So I triangulated some of the scenes and stories where I talked to every relative who was alive for it. I did as much due diligence as possible, reading into every detail of that time and place I could find. And then, as a writer, I stepped into it, following in the footsteps of other nonfiction writers I admire. I call it speculative nonfiction.

LNW: Did you conduct those interviews with your family in person, or was it over software like Zoom? What was your favored method?

SA: I used many different methods. I went to Jordan to see my uncle and cousins at one point. A lot of Zoom, a lot of WhatsApp voice notes—everything I could find. My father thought he didn’t remember certain things, and then it turns out he had repressed certain memories. I tried proceeding with caution as a non-therapist—not trying to drag up things bluntly, but, instead, very delicately. I would wake up sometimes to voice notes from relatives or my father when something just reemerged from their unconscious.

LNW: You cut your teeth doing journalistic writing—covering the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the Trump administration, local news even. What is it about this present moment that has prompted you to turn to more personal essays and memoir writing?

SA: I spent the first few years of my journalism career sort of with a bit of a muzzle on. I feel like I was trying to behave well. I didn’t want to burn any bridges. I didn’t want to out myself as being too leftist, too Palestinian, too angry, too Muslim.… And I think that bought me some time, bought me some bylines, but personally, it felt very suffocating.

I’ve always been very reluctant to write about myself, which may be hard to believe because I wrote this fat book where I’m the main character. But, I’ve continually come into situations where I want to use myself as a frame and a lens to look at things that are larger than me. I hope the choices I made in this memoir about what parts of my personal story to share are all in service of larger questions or broader themes. I got extremely sick, and I spent a lot of my life employed in self-erasure and political compromise. Those forces that harmed me and that disciplined me into self silencing and self erasure still present a danger to many people. So I’m not saying that I have all this wisdom to offer. This is more of a cautionary tale.

Stories are very powerful ways to convey truths that can be theoretical or hard to grasp. Yes, I am a journalist by training, but it’s very freeing to open oneself up to multiple mediums and multiple tools. I try to respond to the need or the impulse or the question and pick up what tools make sense in that moment.

Every day, The Nation exposes the administration’s unchecked and reckless abuses of power through clear-eyed, uncompromising independent journalism—the kind of journalism that holds the powerful to account and helps build alternatives to the world we live in now.

We have just the right people to confront this moment. Speaking on Democracy Now!, Nation DC Bureau chief Chris Lehmann translated the complex terms of the budget bill into the plain truth, describing it as “the single largest upward redistribution of wealth effectuated by any piece of legislation in our history.” In the pages of the June print issue and on The Nation Podcast, Jacob Silverman dove deep into how crypto has captured American campaign finance, revealing that it was the top donor in the 2024 elections as an industry and won nearly every race it supported.

This is all in addition to The Nation’s exceptional coverage of matters of war and peace, the courts, reproductive justice, climate, immigration, healthcare, and much more.

Our 160-year history of sounding the alarm on presidential overreach and the persecution of dissent has prepared us for this moment. 2025 marks a new chapter in this history, and we need you to be part of it.

We’re aiming to raise $20,000 during our June Fundraising Campaign to fund our change-making reporting and analysis. Stand for bold, independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The court’s ruling in Medina v. Planned Parenthood twists logic, common sense, and the law to further the right-wing assault on bodily autonomy.

Elie Mystal

Fifty-four years ago, Katharine Graham defended The Washington Post against presidential threats. Her granddaughter now fears its soul is being sold.

Pamela Alma Weymouth

With a new GOP majority, the incoming FCC boss aims to punish criticism, reward obedience—and screw the public.

Sam Gustin

A new Hulu-produced series by the podcast superstar documents years of sexual harassment and institutional cover-up within Boston University’s athletics department.

Ray Epstein

Deporting people to countries where they might be tortured or killed? All good, according to the six GOP justices.

Elie Mystal

In Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS, a decades-old crisis-response program, may disappear, but the programs it inspired have spread across the United States, including to nearby Portland.

Kaia Sand