Many men lose their Y chromosomes as they age. It may shorten their lives.

Men tend to lose Y chromosome of their cells as they age. But because the Y carries few genes other than those related to male determination, it was thought that this loss would not affect health.

But evidence has accumulated over the past few years that when people with a Y chromosome lose it, this loss is associated with serious diseases throughout the body, contributing to a shorter lifespan.

Loss of Y in elderly men

New techniques for detecting genes on the Y chromosome show frequent loss of the Y in the tissues of older men. THE increase with age is clear: 40% of 60-year-old men have a loss of Y, but 57% of 90-year-old men. Environmental factors such as smoking and exposure to carcinogens also play a role.

Loss of Y only occurs in certain cells and their descendants never recover it. This creates a mosaic of cells with and without Y in the body. Cells without Y grow faster than normal cells in culture, suggesting they might have an advantage in the body – and in tumors.

The Y chromosome is particularly prone to errors during cell division: it can be left in a small bag of membrane that gets lost. We would therefore expect tissues with rapidly dividing cells to suffer more from Y loss.

Why would the loss of the poor Y gene be important?

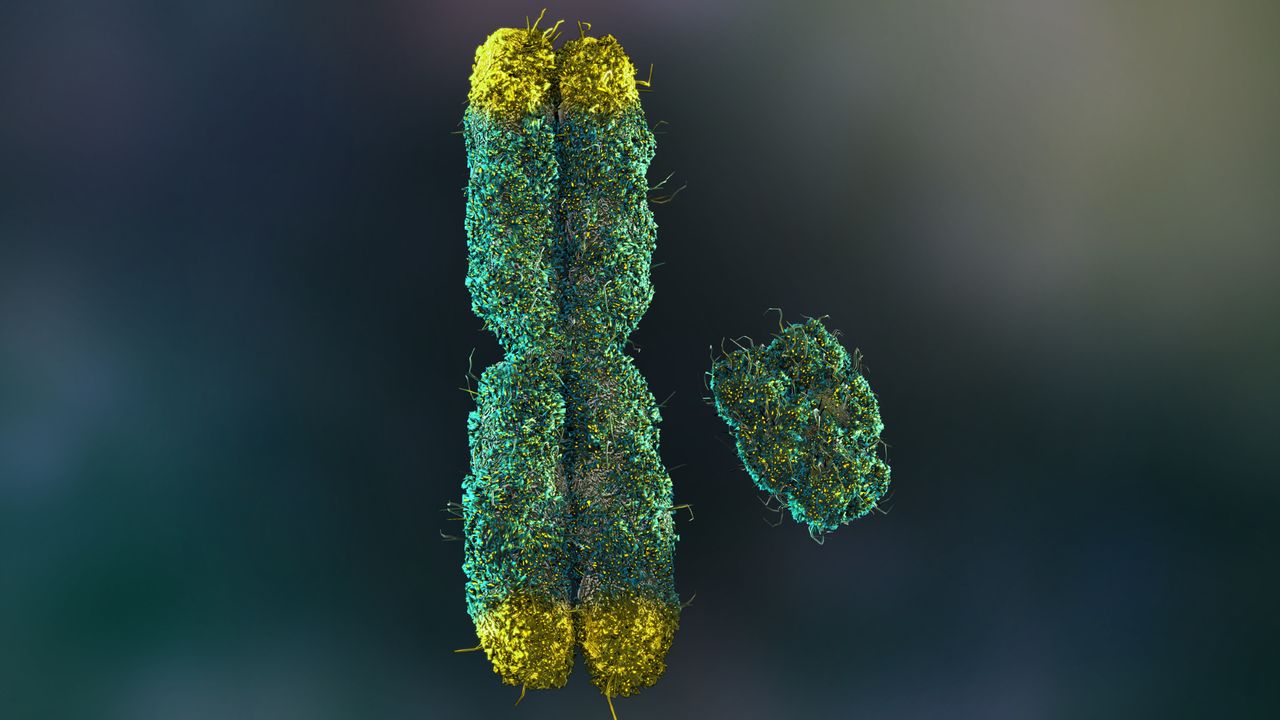

The human Y is a strange little chromosomecarrying only 51 protein-coding genes (not counting multiple copies), compared to thousands on other chromosomes. It plays a crucial role in sex determination and sperm function, but it wasn’t thought to have much else.

The Y chromosome is frequently lost when cells are grown in the laboratory. It is the only chromosome that can be lost without killing the cell. This suggests that no specific functions encoded by the Y genes are necessary for cell growth and function.

In fact, the males of certain species of marsupials abandon the Y chromosome early in their development, and evolution seems to get rid of them quickly. In mammals, the Y has been decaying for 150 million years and has already been lost and replaced in some rodents.

So, the loss of Y in body tissues in old age should surely not be a tragedy.

Association of Y loss with health problems

Despite its apparent uselessness for most cells in the body, evidence is accumulating that loss of Y is associated with serious health problems, including cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. cancer.

Loss of Y frequency in kidney cells is associated with kidney disease.

Several studies now show a relationship between Y loss and heart disease. For example, a very large German study found that men over the age of 60 with high frequencies of Y loss had an increased risk of heart attacks.

The loss of Y has also been linked to death from COVID, which could explain the difference in mortality between the sexes. A ten times higher frequency of Y loss was found in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Several studies have documented associations between loss of Y and various cancers in men. It is also associated with poorer outcomes for those who have cancer. Loss of Y is common in cancer cells themselves, among other chromosomal abnormalities.

Does loss of Y cause disease and mortality in older men?

It is difficult to determine the causes of the links between Y loss and health problems. They may arise because health problems cause loss of Y, or perhaps a third factor could be causing both.

Even strong associations cannot prove causation. The association with the kidney or heart disease could result from rapid cell division during organ repair, for example.

Cancer associations may reflect a genetic predisposition to genome instability. Indeed, genome-wide association studies show that the Y frequency loss is approximately one third geneticinvolving 150 identified genes widely involved in cell cycle regulation and cancer susceptibility.

However, a study on mice indicates a direct effect. The researchers transplanted Y-deficient blood cells into irradiated mice, which then showed an increased frequency of age-related pathologies, including poorer heart function and subsequent heart failure.

Similarly, loss of Y from cancer cells appears to directly affect cell growth and malignancy, possibly lead to ocular melanomawhich is more common in men.

Role of Y in body cells

The clinical effects of Y loss suggest that the Y chromosome plays important functions in the body’s cells. But given how few genes it harbors, how?

The human-determining SRY gene found on the Y is widely expressed in the body. But the only effect attributed to its activity in the brain is complicity in causing Parkinson’s disease. And four genes essential for sperm production are only active in the testicles.

But among the other 46 genes in the Y, several are widely expressed and serve essential functions in gene activity and regulation. Several are known cancer suppressors.

These genes all have copies on the X chromosometherefore males and females have two copies. It may be that the absence of a second copy in cells without Y causes some sort of dysregulation.

In addition to these protein-coding genes, the Y contains many non-coding genes. These are transcribed into RNA molecules, but never translated into proteins. At least some of these non-coding genes appear to control the function of other genes.

This could explain why the Y chromosome can affect activity genes on many other chromosomes. Loss of Y affects the expression of certain genes in cells that make blood cells, as well as others that regulate immune function. It can also indirectly affect the differentiation of blood cell types and heart function.

THE Human Y DNA was only fully sequenced a few years ago – so in time we will be able to discover how particular genes cause these negative health effects.

This edited article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.