Mathematicians Make Surprising Breakthrough in 3D Geometry with ‘Noperthedron’

October 28, 2025

2 min reading

This new shape breaks an “unbreakable” 3D geometry rule

Noperthedron has a surprising property that disproves a long-held conjecture

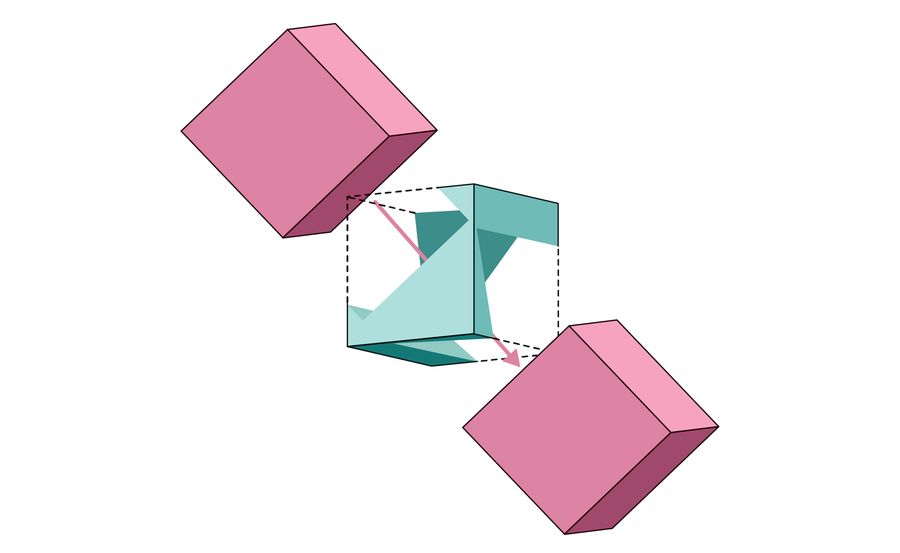

Can you drill a hole in a cube through which an identical cube could fall? Prince Rupert of the Rhine first asked this question in the 17th century, and he soon discovered that the answer was yes. We can imagine propping a cube on its corner and drilling a square hole large enough vertically to accommodate a cube of the same size as the original.

Later, mathematicians discovered more and more three-dimensional shapes that came to be called “Rupert”: they are capable of falling through a straight hole with an identical shape. In 2017, researchers formally hypothesized that all 3D shapes with flat, non-indented sides, known as convex polyhedra, were Ruperts. No one has been able to prove them wrong, until now.

On supporting science journalism

If you enjoy this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscription. By purchasing a subscription, you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

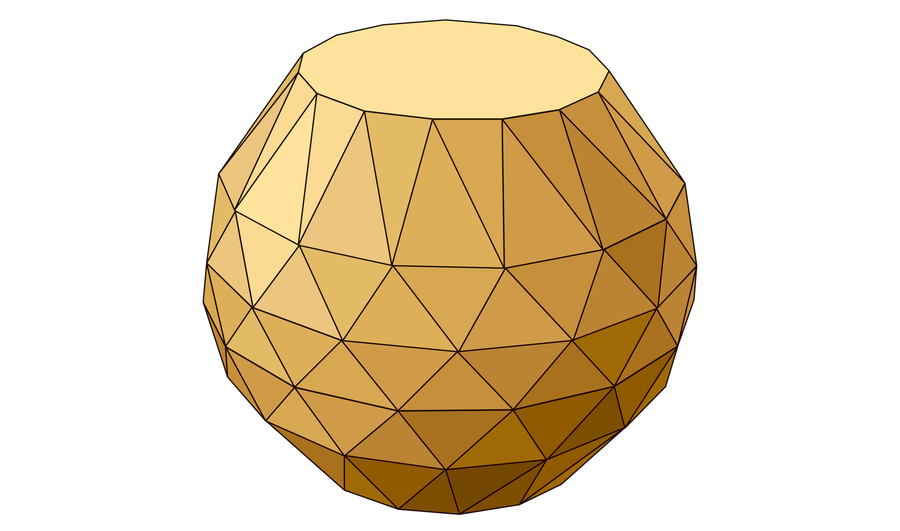

Enter the all-new noperthedron. It has 90 vertices, 240 edges, 152 faces and a very special property: it is “nopert”, a word coined this year by independent computer scientist Tom Murphy VII to mean “not Rupert”. Mathematicians Sergey Yurkevich of Austrian technology company A&R Tech and Jakob Steininger of Statistics Austria, the country’s national statistical institute, recently introduced the new form to the world in a paper published on the preprint server arXiv.org. Noperthedron is not the first form suspected of being nopert, but it is the first to be proven so – and it was designed with certain properties that simplify the proof. Using a custom-made computer program, the researchers were able to verify that no matter how each of two identical noperthedrons is moved or rotated, one would not be able to fall through a hole into the other.

Yurkevich and Steininger have been studying Rupert’s property for years and working together for even longer; the two men met when they were teenagers preparing for a mathematics Olympiad. “After so many years, we know each other’s strengths,” Steininger says. Yurkevich adds, “If one of us says something that doesn’t make sense, the other has no problem saying, ‘I have no idea what you just said.’ »

They first came across Prince Rupert’s Cube on YouTube as university students, and quickly discovered that the prevalence of these solids was an open problem. In a 2020 paper, Yurkevich and Steininger were the first to publicly conjecture that not all convex polyhedra have Rupert’s property. Now, five years later, they have taken their conjecture to proof.

The researchers described the set of all possible noperthedron holes as a five-dimensional cube, with each axis representing a different rotation of the polyhedron. Using a clever mix of mathematical reasoning and computer programming, they considered each area of this cube as a possibility. “Their approach is both creative and rigorous,” says Pongbunthit Tonpho, a mathematician at Chulalongkorn University in Thailand who studies Rupert’s property. “I didn’t expect anyone to be able to disprove this hypothesis so soon.”

It’s time to defend science

If you enjoyed this article, I would like to ask for your support. Scientific American has been defending science and industry for 180 years, and we are currently experiencing perhaps the most critical moment in these two centuries of history.

I was a Scientific American subscriber since the age of 12, and it helped shape the way I see the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of respect for our vast and magnificent universe. I hope this is the case for you too.

If you subscribe to Scientific Americanyou help ensure our coverage centers on meaningful research and discoveries; that we have the resources to account for decisions that threaten laboratories across the United States; and that we support budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In exchange, you receive essential information, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, newsletters not to be missed, unmissable videos, stimulating games and the best writings and reports from the scientific world. You can even offer a subscription to someone.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you will support us in this mission.