Can you see circles or rectangles? And does the answer depend on where you grew up? | Anil Seth

Do People of different cultures and environments see the world differently? Two recent studies have taken different from this controversy of several decades. The answer could be more complicated and more interesting than one or the other study suggests.

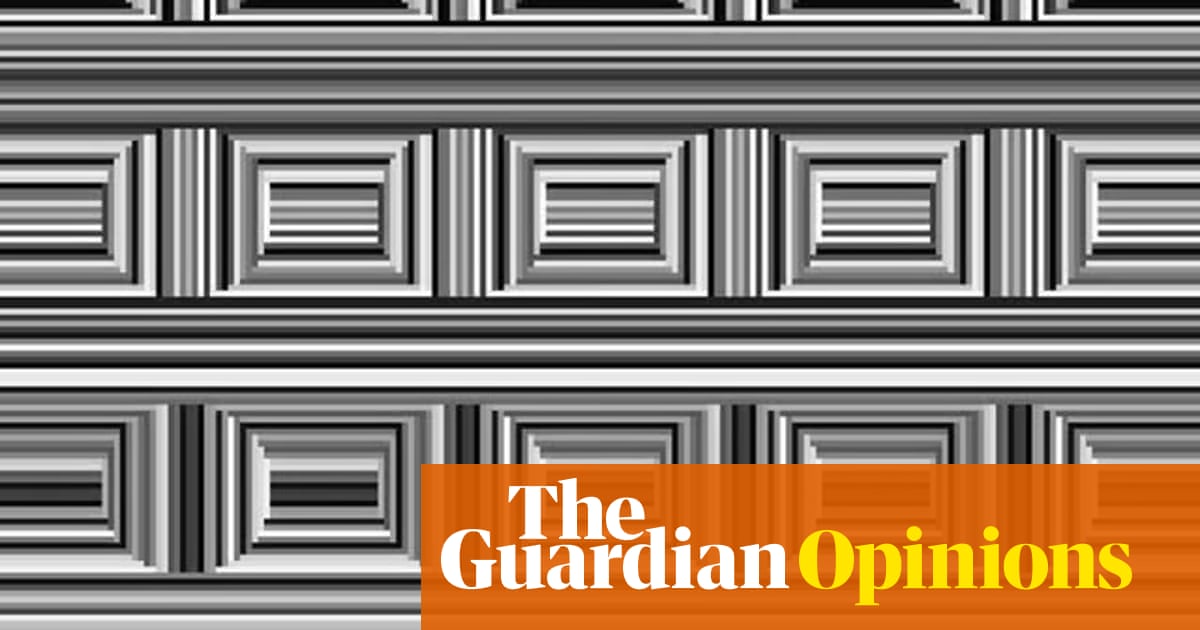

A study, led by Ivan Kroupin at the London School of Economics, asked how people of different cultures perceived a visual illusion known as the trunk illusion. They discovered that the inhabitants of the United Kingdom and the United States have seen it mainly in a way, such as comprising rectangles-while people from rural communities in Namibia have generally seen it another way: as containing circles.

To explain these differences, Kroupin and his colleagues call on a hypothesis raised over 60 years ago and have been arguing since. The idea is that the inhabitants of Western industrialized countries (nowadays known by the “bizarre” acronym – for the West, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic – a summary which is increasingly questionable) see things in a specific way because they are generally exposed to very “carpenters” environments, with many straight lines, right -handed angles – common -visual architecture. On the other hand, the people of non -“bizarre” societies – like those of rural Namibia – inhabit environments with fewer net lines and angular geometric shapes, so that their visual capacities will be adjusted differently.

The study argues that the tendency of rural Namibians to see circles rather than by rectangles in the illusion of trunk is due to their home dominated by structures such as round huts instead of angular environments. They support this conclusion with similar results from several other visual illusions, all supposed in the basic mechanisms of the brain involved in visual perception. Until now, everything is fine for intercultural perceptual psychologists and for the hypothesis of the “world of the frame”.

The second study, by Dorsa Amir and Chaz Firestone, brings a hammer to this hypothesis, but for the much better known illusion: the illusion of Müller-Lyer. Two lines of equal length seem to be different lengths due to the context provided by the pointing arrow tips inwards, compared to the arrow tips. It is a very powerful illusion. I saw it on thousands of occasions and it works every time for me.

There are many explanations to explain why Müller-Lyer’s illusion is so effective. One of the most popular is that arrow tips are interpreted by the brain as clues to a three -dimensional depth, so our brain implicitly interprets illusion as representing any object, with right angles and straight lines. This explanation corresponds perfectly to the hypothesis of the “threatened world” – and in fact a lot of early support for this hypothesis was based on an apparent cultural variability in the way in which the illusion of Müller -Lyer is perceived.

In their study, Amir and Firestone carefully and convincingly dismantle this explanation. They underline that non-human animals experience the illusion, as shown in a range of studies in which animals (including guppies, pigeons and bearded dragons) are formed to prefer the longest of two lines, then presented with the image of Müller-Lyer. They show that it works without straight lines, and to touch it as well as vision. They note that it works even for people who, until recently, have been blind, referring to an astonishing experience in which nine children, blind from birth due to dense cataracts, showed the illusion immediately after the cataracts were removed surgically. Not only had these children saw highly carpenters’ environments – they had seen nothing at all. After having absorbed their analysis, it is quite clear that the illusion of Müller-Lyer is not due to a culturally specific exhibition for carpentry.

Why the gap? There are several possibilities. There are perhaps reasons why intercultural variability should be expected to coffer it but not the illusion of Müller-Lyer (one possibility here is that the illusion of trunk is based on the way people pay attention to things, rather than on a more fundamental aspect of perception). There may also be systematic differences in perception between cultures, but that the “threatened world” hypothesis is not the correct explanation. It should also be noted that the Kroupin study has potential weaknesses. For example, the British / United States and Namibian participants were exposed to illusions using very different methods. Overall, the jury remains extinguished and – a boot of clearance of favorite scientists to come – “more research is necessary”.

The idea that people from different cultures vary in the way they experience things is certainly plausible. There are a multitude of evidence that when we grow, our brains are shaped, at least to a certain extent, by characteristics of our environments. And just as we all differ in our visible external characteristics – height, body shape, etc. – We will all differ also inside. As the author Anaïs Nin said by quoting the Talmud: “We do not see things as they are, we see them as us.”

For me, an important involvement of this line of thought is that there are probably substantial differences in perception In “Groups” as well as between them. This will probably hold these “groups”, however, are defined, whether as different cultures or as a contrast between “neurotypical” and “neurodivergente” people. I believe that paying more attention to the intra-group perceptual diversity will help us to better interpret the differences we find between the groups and equip ourselves with the tools necessary to resist relying on simple cultural stereotypes as an explanation.

Additional research is also necessary here. But it’s on the way. In the census of perception, a project led by my research group at the University of Sussex with Professor Fiona Macpherson at the University of Glasgow, we study how perception differs in a large sample of around 40,000 people of more than 100 countries.

Our experience includes not only one or two visual illusions, but more than 50 different experiences by probing many different aspects of perception. When we have finished analyzing the data, we hope to provide a particularly detailed image of how people experience their world, inside and between cultures. We will also make data available openly for other researchers in order to explore new ideas in this important area.

A critical overview lies behind all these questions. How things don’t seem to be how they are.

For each of us, it may seem that we see the world exactly as it is; As if our senses were transparent windows with the world spilled directly into our mind. But how are things very different. The objective world undoubtedly exists, but the world we live is always an active construction, a kind of “controlled hallucination” in which the brain uses sensory signals to update and calibrate its best interpretation of what is happening. What we live is this interpretation, not a “reading” of sensory information.

For me, it is the key key that underlies any assertion on perceptual diversity. When we take it fully on board, it encourages a much necessary humility about our own ways of seeing. We live in perceptual echo rooms, just as we do in those of social media, and the first step to escape any echo room is to realize that you are in one.