Before Sebald Was Great | The Nation

Books & the Arts

/

July 28, 2025

By looking at his early work, we can better understand who the German writer was beyond his persona as the melancholy intellectual and serious man of letters.

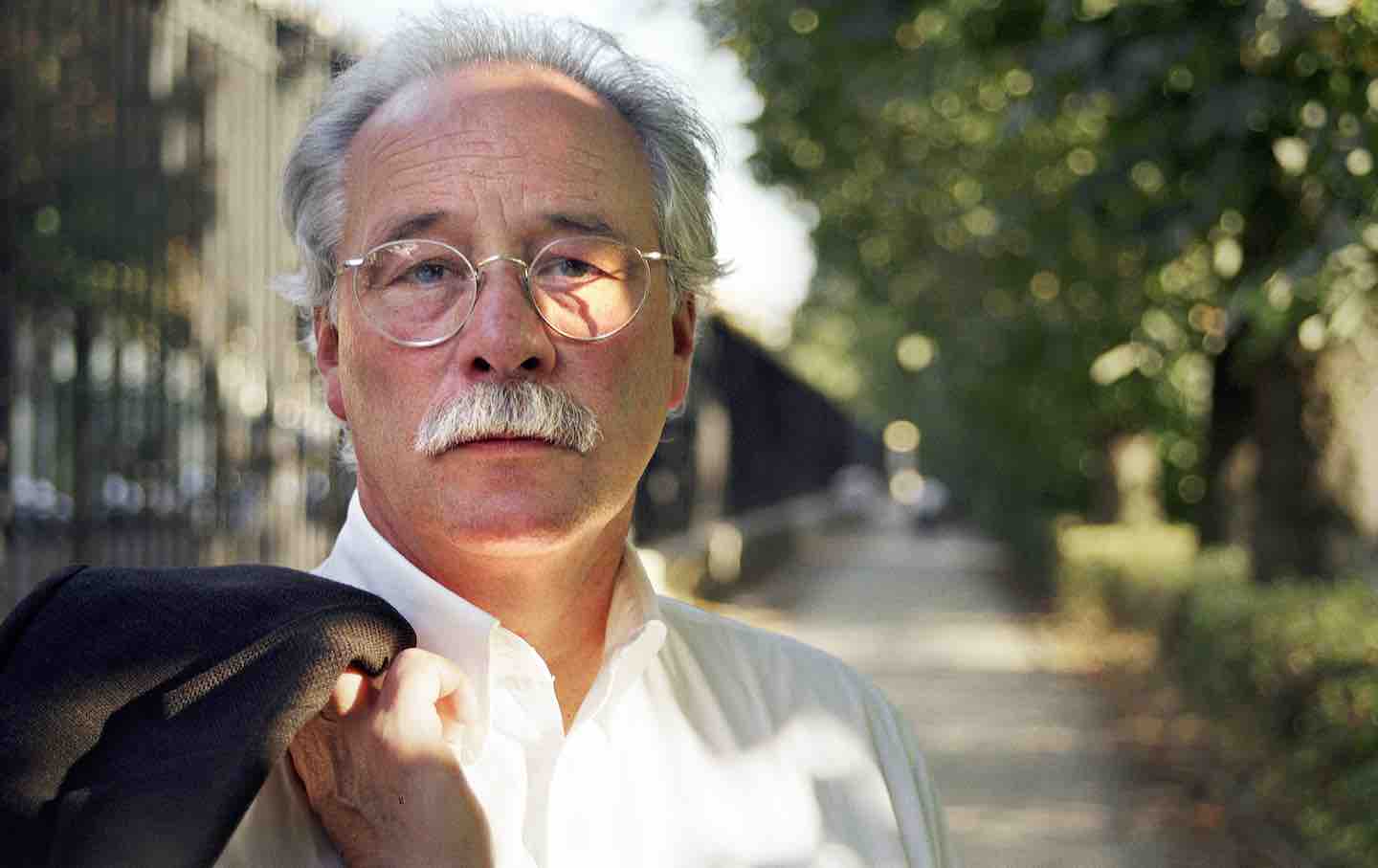

W.G. Sebald, 1999.

(Ulf Andersen / Getty Images)

Since his death in 2001, the reputation of W.G. Sebald has become formidable, even imposing. At times, he feels like a totem: the Western world’s last Absolutely Serious Writer. The German English author of novels (or simply works of “prose” if you prefer, as he did) has cast a long and melancholy shadow over the literature of the 21st century: Deeply erudite and formally inventive, his work absorbed the weight (or burden) of European history and literature and established a new model for writers. For those unconvinced by “merely” aesthetic novelties, he was unafraid to wrestle with ethical questions, most famously Germany’s confrontations with historical memory and its inability to fully process the Holocaust. For many—he does have his detractors—he was the capstone of literature in the 20th century, both burnishing and waving goodbye to a sophisticated culture on the wane.

Books in review

Silent Catastrophes: Essays

Buy this book

Something he is not: funny. (Critics have occasionally argued otherwise, but I don’t really believe them.) If whimsy occasionally surfaces—the skull of Sir Thomas Browne in The Rings of Saturn, the nocturnal zoo of Austerlitz—there is also nothing frivolous. Irony only ever arrives in whispers. Sebald’s floating, elegiac intelligence stimulates a mindset: While reading him, we, too, can put away childish things and take up questions of truth and beauty; if we can hold ourselves there with him, we might glimpse the profound in ourselves. Most people today don’t inhabit a lifeworld like Sebald’s ruminations, and so perhaps this is his draw: Take him seriously, and thereby take yourself seriously, too.

Unsurprisingly, a huge body of criticism has piled up around Sebald, most of which follows the same broad strokes. You can stress-test his moral commitments, or analyze his technique in crossing the streams of fiction and nonfiction. You can point out his influence on “innovative” fiction writers of the last decade (Teju Cole, Ben Lerner, Rachel Cusk, Benjamín Labatut, etc.). These measurements of inheritance are frequent because they are one way that critics track a writer’s stock (leaving aside that Sebald was so often an enthusiast of supposedly minor artists, like the Swiss writer Robert Walser). Sebald’s iconic style has been incorporated into the literary bloodstream. In an essay for New Left Review, the critic Ryan Ruby helpfully characterizes its hallmarks:

Sebald’s writing is known for four things: its thematic preoccupation with the after-effects of the Holocaust and the Second World War; the interspersion of photographs, documents and reproductions of paintings and other visual media throughout the texts; the floridity, antiquarianism and melancholy tone of its prose; and, finally, its so-called ‘metaphysics of coincidence’, the way an apparently associative series of random details and incidents makes it difficult to tell how one sentence follows from the next, only for the whole to reveal itself, in the end, as having operated according to a complex, lattice-like order from the beginning.

Although it’s hard to dispute the accuracy, there’s also something a bit dispiriting in seeing the “Sebaldian” formula laid out so neatly. Mystery, where art thou?

Still, anyone who’s read a Sebald novel, or even part of one, can conjure it. There’s that slightly fuzzy and tweedy narrator, teasingly like Sebald himself. He’s out for a walk, or in a train station or some other threshold place. He is struck by an object—a picture postcard, a stray image in his sight line—and a little knot of story forms and is incorporated into the weave. Or maybe it’s not a story, but more of an essay, or a close reading; as one considers, it becomes less clear how these are distinguished. Uncertainty is part of the experience: We wend with the author, we dream, we associate, we search our own feelings. Without feeling a little lost, the prose has lost its purpose.

For a writer who thinks with poetic leaps and complex retracings of memory, Sebald, a quarter century on, has come to seem slightly dusty. Is there a way we might feel reenchanted by his writing? This is not to say that the reader of Sebald should abandon their critical faculties, but that it may be necessary to regain a view of the pleasures, both intellectual and aesthetic, that he can still offer, and think less in terms of reputation and reception. The way to do this might be to return to when he had none: to read a less “great” Sebald might help dislodge him from stereotype. Silent Catastrophes, a new English edition of Sebald’s early critical and academic writings—primarily on Austrian literature—translated by Jo Catling, allows us to catch sight of this less polished, mysterious figure. The essays are a personal genealogy of some of Sebald’s important German-language predecessors, and at the same time a window into an author in the process of self-making.

Current Issue

Sebald was born in 1944 in Wertach, a village just across the border in southern Bavaria. Catling remarks in her introduction that “this sense of being from the margins” helps explain Sebald’s affinity for the literature of neighboring Austria. This was a feeling of living on the periphery of world-historical disaster—World War II and above all the Holocaust: knowing without witnessing, feeling distanced but still inside the complicity of silence. In addition, what “Austrian literature” is, exactly, considering the shifting borders and cultures of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, is another ambiguity that suits Sebald. He writes that he does not mean to be comprehensive, but his inventory includes writers well-known to the Anglophone reader—Kafka, Thomas Bernhard, Peter Handke—and writers less so, like the 19th-century adventurer Charles Sealsfield, whose wanderings in the American South make him sound like a character in a Sebald novel; and Adalbert Stifter, a petit bourgeois chronicler of natural beauty who would be rediscovered in the early 20th century as a master stylist. Jewish writers, as one might expect, are also well-represented, from Kafka to Joseph Roth to the Holocaust survivor and self-exiled writer Jean Améry, along with an essay on the micro-genre of life sketches from the Jewish ghetto.

Silent Catastrophes is really two separate books, their titles translated by Catling as The Description of Misfortune (1985) and Strange Homeland (1991). Gathered together, they bracket a formative period in Sebald’s career, arriving on either side of his emergence as a creative writer. In 1988 and 1990, respectively, Sebald published the poetry collection After Nature and his first prose fiction, Vertigo. Many of the essays in the new volume appeared in the Austrian journal manuskripte, the same place where early fragments from Vertigo and The Emigrants would be published. Similarly, subjects like the schizophrenic poet Ernst Herbeck and the Viennese writer Peter Altenberg became figures in Vertigo as well.

Sebald was working to invent himself as a writer in this period, and it’s clear in Silent Catastrophes that his method was already unorthodox. The essays often have little in the way of argument or real organization. Long block quotes can feel arbitrary, theorists are cited and then dispensed with, and the prose lurches between extended close readings and brilliant observations that jump off the page. For a reader new to Sebald, this collection would surely be the last place to start. Inevitably, many of Sebald’s epigrams feel aspirational for his own writing—when Sebald describes in Handke’s work a “hope for redemption from the guilt-ridden conditions of life, a hope fleetingly realized in art…which yet remains ever strange to us,” I sense his own striving. In their meandering style, the essays harbor an oppositional force welling up through the “correct” form of criticism.

Although the two books are closely related (essays on Kafka and Handke, for instance, show up in both) each is loosely based around a single idea. The Description of Misfortune deals with psychology, particularly “the unhappiness or misfortune [Unglück] of the writing subject.” Sebald’s attention to mental illness and misery evoke a curiously Romantic idea of the suffering artist, though he never commits to any overarching interpretation. He also explores some subjects that are rare in his fiction, particularly erotic desire and perversity, as illustrated in the works of Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Arthur Schnitzler (whose Dream Story is best known here as the loose source material for Stanley Kubrick’s film Eyes Wide Shut). Freud, naturally, is the Viennese touchstone (“If it is true that one should not read Schnitzler without Freud, then the reverse is equally true”) against which Sebald asserts art’s unique ability to represent consciousness. Sebald wants to claim a privileged place for literature—that it can do something beyond what theory does—but finds himself working through the theoretical language that is native to him.

Sebald often returns to the word pathography—the study of a life through the lens of a particular ailment—and perhaps the urge to be a writer is one such malady, an idea that he would return to in his later essay collection A Place in the Country. Sebald is weighing for himself the idea of choosing art: What lies behind the urge to become a writer? What are the spiritual costs? Clearly Sebald hoped to jump the boundary between critic and artist: not to simply be a commentator, but to join the fraternity of the afflicted.

The most polemical moment of Misfortune comes in its preface, in which Sebald suggests that the idea of melancholy, perhaps the central emotional state of all of Sebald’s work, is not a cloistered writer’s defect but instead a positive force:

Melancholy, the contemplation of disaster in progress, has, however, nothing in common with a desire for death. It is a form of resistance. And on the level of art, in particular, its function is anything but reactive or reactionary. When, with a fixed stare, Melancholy considers once more how things could have come to this, it becomes clear that the mechanics of hopelessness are identical to those which drive our knowledge and insight. The description of misfortune contains within it the possibility of its own overcoming.

This is an intriguing assertion, though Sebald never really demonstrates it. Perhaps the evidence was conjured in Sebald’s own fiction. But does the melancholy in Sebald really contain a seed of “resistance”?

Considering the psychological bent of the collection, one turns to Freud’s classic essay “Mourning and Melancholia.” In it, Freud distinguishes between two forms of grief: In mourning, there is a struggle to release our attachment from what we’ve lost, but what was lost is certain—for instance, a loved one who has died. In melancholy, by contrast, the object of grief remains repressed; we’re not sure what we’ve lost, or even if we’ve really let go. The ambivalence of the latter is fitting in thinking about Sebald, but what, exactly, is being resisted? Freud suggests that melancholy is ultimately a retreat into narcissism—a problem to be fixed for a clinician, but not necessarily for a writer. More negatively (and more politically), one might turn to Walter Benjamin’s essay “Left-Wing Melancholy,” in which Benjamin writes that a defeated left, finding itself in retreat, indulges itself by taking stock of its feelings. The sufferer of left-wing melancholy looks inward only to find that “what is left is the empty spaces where, in dusty heart-shaped velvet trays, the feelings—nature and love, enthusiasm and humanity—once rested. Now the hollow forms are absent-mindedly caressed.” Benjamin’s phrase has become a shorthand for the malaise of left intellectuals who, having lost their belief in the revolutionary project, are left to linger. An uncharitable view of Sebald might see exactly these “velvet trays” as the building blocks of his art.

Sebald makes no claim to be a revolutionary artist, and even his thoughts on melancholy seem to shift by the time of Strange Homeland, as he praises Handke’s ability to “withstand the temptations” of melancholy, but here we catch him struggling to justify his attraction to his darker humor. Sebald was undoubtedly aware of Freud’s and Benjamin’s misgivings. But what can anyone do but write their own temperament truly? Even a writer who began by speaking through a screen of intellectual heft still had reasons to pursue stronger feelings than a cold intellectualism. Writing at a time when victory for the left seemed as distant as it had ever been, Sebald took his investigations into smaller spaces, just like the 19th-century writers such as Stifter, whom Sebald admired for their patient tracing of the details. Sebald repurposed his melancholy, and perhaps began working outward into the world again. It is no accident that his final novel, Austerlitz, is his closest look at the horrors of the Holocaust.

In an essay written later in his career about German literary responses to World War II, Sebald asserts that “literature today, left solely to its own devices, is no longer able to discover the truth.” Of course, Sebald’s skepticism toward the powers of traditional literature could be attributed to melancholy, a sense that the old methods have been defeated. At the same time, this modesty is part of taking literature’s powers seriously. Pretending at power when you have none is to set off in error. “To its own devices” is a typically double-edged idea itself, one not to be taken entirely at face value. A feeling of literature left powerless is also a call to intervene, to find new devices, new methods to shake readers from their complacency.

If The Description of Misfortune is dedicated to the peculiar mental state of being a writer, the second volume, Strange Homeland, or Unheimliche Heimat, turns outward toward social life. “Unheimliche” is translated here as “strange,” but it can also mean “uncanny,” another Freudian grace note. If the earlier volume asks the question of what it’s like to be a writer, Strange Homeland is written with a new confidence that its author has, to some degree, proven himself, and so takes on a wider set of political and social concerns, particularly the question of belonging and Heimat, or homeland (which, pointedly, Catling retains in the German throughout the text). Heimat is a deep source of ambivalence: On one hand, it must be viewed critically in the wake of Nazi crimes and the pitfalls of nationalistic revanchism everywhere. On the other, it is the backdrop for the wanderer—that figure so central to Sebald’s fiction—who must go on a journey without ever being sure he can come home again. The Heimat is a shadowy place for Sebald, both an illusion and our last chance of finding footing in a hostile world. As he writes with pathos about Améry, who gave up Austria and even his old name after surviving the Holocaust, “For what can we call our own, if not our home country?”

In writing about Austria, Sebald sharpens his focus as a writer of imperial decline. In his essay about Joseph Roth, the Jewish journalist and novelist best known for The Radetzky March, Sebald invokes the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a lost homeland, one with no precise relationship to experience today, but which still extends a ghostly memory into European consciousness. For Sebald, there is dignity in Roth’s humanism and fatalism, his dedication “to the symbolic salvation of a world he already knew to be doomed.” For Sebald, Jewish life is the highest form of estrangement from the Heimat; Roth, having lost the empire, is an exile twice over. Typically evasive, Sebald never quite makes a conclusive statement about the meaning of homeland, choosing instead to defer to contradictions that don’t entirely satisfy: “For the wandering Jews, however, among whose number Roth counts himself, and whose graves, as he writes, are everywhere, Heimat is nowhere–and thus the epitome of utopia.”

The writing here is more focused and crafted than in Misfortune—the reader gets a few glimpses of the Sebald to come. Catling, in her introduction, writes that Sebald’s more biographical approach was a departure from the standard German literary criticism of the time, which had remained resolutely focused on close reading. The narrowness of this textual criticism was seen by Sebald as a dodge by the keepers of German culture as they turned away from the dark historical truths of Germany’s 20th century. But this turn toward lived life was also the beginning of an artistic blooming. His essay on Améry ends with a strange—uncanny, even—anecdote of Améry meeting Thomas Bernhard “mid-tirade” in a bar by chance shortly before committing suicide. The autobiographical creeps in around the edges, too, as when Sebald, thinking about our feeling for nature, remembers how he saw “his grandfather raise his hat to an elder bush.”

In the collection’s final essay, on Handke’s Repetition, Sebald praises the novel’s literary powers, particularly its lightness and striking imagery, and wonders if “our natural Heimat might yet be saved after all.” Considering Handke’s future embroilment as a controversial spokesperson for Serbia in the wars that tore apart the former Yugoslavia, there is some irony here. The redemption of the Heimat is a comforting thought, but perhaps it is more helpful to think of this statement, along with the others, as a provisional stage of Sebald’s thought process that continued to evolve in his fiction. Could the homeland be redeemed? Reading Sebald’s later works, like The Rings of Saturn or Austerlitz, one is hardly sure of a positive outcome, though the question hangs in the air, still unanswered.

In his essay on Adalbert Stifter, Sebald shows a profound sympathy for the Biedermeier writer, another melancholic sketching nature from the periphery. Stifter might seem at first like a kind of literary naïf: His stories highlight the beauty of flowers, forests, and snowdrifts more than he directly tackles any great theme. In appraising him, Sebald begins with a capsule biography (dwelling on his gluttony, his family and career misfortunes, his suicide), but he also praises Stifter’s work for its style—its patience for small-scale beauty, its lack of fidelity to plot. Sebald insists that something contradictory is at work under this pretty surface: “The scrupulous registering of the most minute details, the endless enumeration of what–strangely enough–is actually there: all bear signs of a lack of belief, and mark the point at which even the bourgeois doctrine of salvation could no longer be sustained.” The nature that Stifter inventories so carefully, as if to preserve it, is already well on the way toward annihilation. (Throughout all the essays in Silent Catastrophes, the idea of man’s destruction of the environment runs like a drumbeat through the background.) Stifter, then, is a kind of unconscious registrar of catastrophe: He may not even know that his world is lost, but his receptivity allows him to sense the truth and express it implicitly. His secret subject is “a release from the uncanny nature of time itself.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Might we think of Sebald as a writer whose work, like Stifter’s, sees the future out of the corner of its eye, even as it looks back? The Freudian sense of melancholy is fitting here—as an artist, Sebald radiates care and attachment to the small things as well, but his work also cannot speak the name of what it has lost. After all, do any of us know what we are losing? The world is always undergoing a process of reshaping itself, slipping through our fingers as we try to hold on; reality itself is in flux, and a new reality effect must be devised. Sebald was in the business of looking for new techniques.

In Carol Angier’s (generally maligned) biography of Sebald, it came to light, perhaps unsurprisingly, that many of Sebald’s sources were manipulated—perhaps most controversially his conversion of non-Jewish sources into Jewish characters in his novel The Emigrants. Similarly, images in his work were often not what the narrator or author claimed them to be. Fictional license is expected, and the manipulation of images hardly new, but again Sebald seems predictive of a time when images are even less reliable than we thought. We are entering an era of mass image production in which perhaps the majority of images will be “false,” synthesized by AI. Sebald’s later focus on images (there are none in Silent Catastrophes) can be seen now less as “evidence” than a polemic for the coming reality, where we experience the destruction of our steady sense of visual truth, even as we continue to rely on its inputs. As Sebald said in his interview with Michael Silverblatt (his last interview before his death), reflecting on the obligation or the ability to write about the Holocaust:

We’ve all seen images [of the concentration camps], but these images militate against our capacity for discursive thinking, for reflecting upon these things. And also paralyze, as it were, our moral capacity. So the only way in which one can approach these things in my view is obliquely, tangentially, by reference rather than by direct confrontation.

Sebald’s images, rather than supplying an artificial fidelity, encourage us to think harder about how we know what we know and why we believe what we believe. The closer we look, the less certain we become.

Sebald’s most enduring connection in Silent Catastrophes, the writer who he returns to again and again, is Kafka. Sebald is particularly focused on Kafka’s final masterwork, the enigmatic, unfinished novel The Castle. Although it may not be obvious at first, similarities between the novel and Sebald’s literary output are evident. A thinly disguised alter ego (Kafka originally began drafting his novel in the first person before changing the “I” pronouns to the now-famous “K.”) arrives at a strange, unnamed village with an ostensible task—he seems to be a land surveyor—only to be overwhelmed by detours and uncertainties, unsure if he will ever make any progress. Moreover, Kafka gives us a sense that while the objective remains the same (to reach the castle), the rules are always subject to change, both in the novel and in his style. This flexibility, the idea that at any moment a new invention might be unearthed, even unconsciously, seems at the heart of Sebald’s affinity.

Tantalizingly, Sebald reads K. as a kind of revolutionary who is incapable of seizing the moment when it arrives: “Kafka’s way of representing the dilemma seems to imply that a revolution is nevertheless necessary and that it is all the more imperative the more impossible it becomes to translate its idea into practice.” This reading is some ways away from the typical idea of “the Kafkaesque,” which so quickly clouds a reader’s vision, confirming Kafka’s status while diluting his work’s vitality. In Sebald’s work, there are also patterns with which we are overfamiliar. But by seeing Sebald as a writer inventing the rules as he went along, we go with him deeper into his mystery and melancholy—his search for a method, however oblique, that might begin to dislodge the impossible. For literature, there still might be infinity in a grain of sand on a Suffolk beach.

More from The Nation

The real Man of Steel wasn’t woke, but he was radical.

Jeet Heer

The Prince of Darkness, who gave us heavy metal as we know it, has been laid to rest.

Obituary

/

Kim Kelly

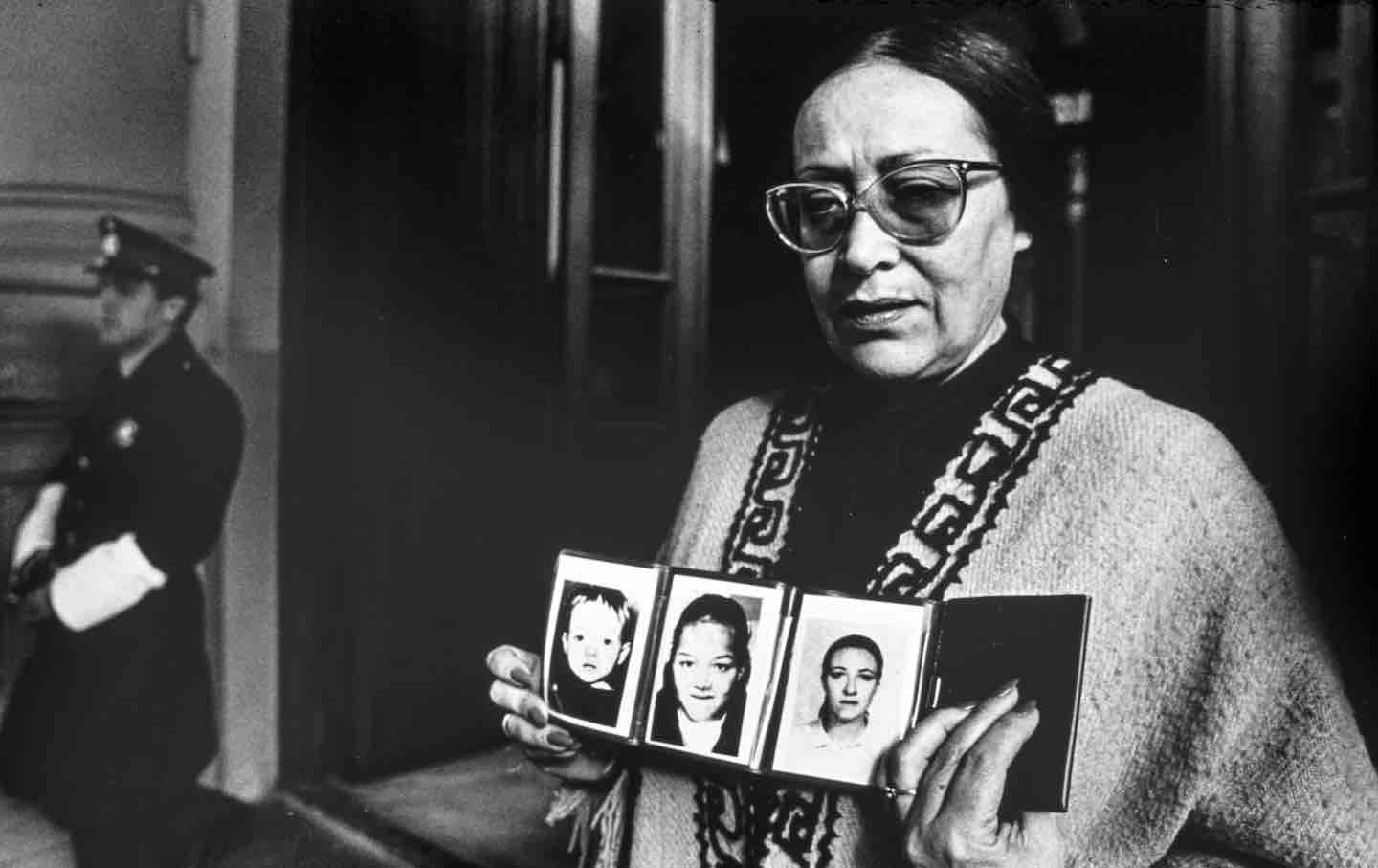

Haley Cohen Gilliland’s A Flower Traveled in My Blood looks at the efforts of a human rights group to find the children and grandchildren who were disappeared by a dictatorship.

Books & the Arts

/

Jacob Sugarman

Why the beauty and inventiveness of contemporary masonry in Iran has captured Western audiences.

Kate Wagner

Alexander Clapp’s Waste Wars, a world-spanning inquiry into the politics of garbage, makes a case that everything that is wrong with capitalism is embodied in our trash.

Books & the Arts

/

Carol Schaeffer

Emily Callaci’s history of the international feminist movement examines the influence of their intellectual and political victories.

Books & the Arts

/

Maia Silber