Scientists heat gold to 14 times its melting point — without turning it into a liquid

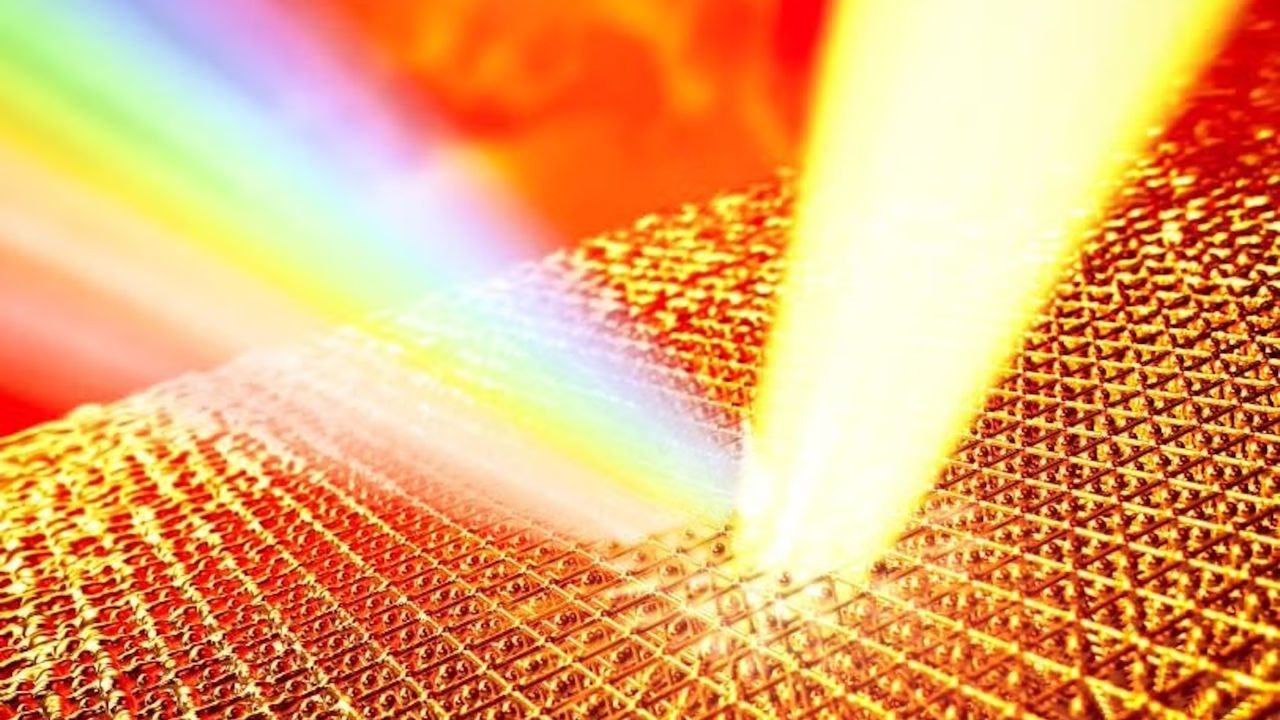

Scientists have used high intensity ultra-fast lasers to overheat gold 14 times its melting point without transforming solid metal into liquid.

Record experience, which was described in a study published on July 23 in the journal NatureBroken a theory of several decades on the stability of solids and is the first reliable method to precisely measure the temperature of extremely hot systems, the researchers said.

Unusual material states, such as plasma surrounding the sun or high pressure planets, can reach incredible temperatures of millions of Fahrenheit degrees. However, in fact putting a figure in this so-called “hot dense matter” proved to be difficult, because scientists have struggled to measure the hot short-term material fairly quickly to obtain reliable results.

“We have good techniques to measure the density and pressure of these systems, but not the temperature”, author of the study Bob NaglerA scientist from the National Accelerator Laboratory of the SLAC of the Ministry of Energy, said in a statement. “In these studies, temperatures are always estimates with huge error bars, which really maintains our theoretical models – this was a problem of several decades.”

The speed was therefore essential to take a successful measure. To achieve this, the team used 45-femtosecond X-ray laser pulses (45 quadrillions of a second) to quickly heat a thin gold film. When the radiation passed through the crystalline film, the atoms vibrated at a frequency directly linked to their increasing temperature. A second impulse drawn on the hot sample then diffused these vibrating atoms, and the frequency discrepancy of these deflected beams provided a quantitative measure of the speed of atoms and therefore of the temperature.

However, the researchers realized that they had realized much more than a new measurement technique. “We were surprised to find a much higher temperature in these solid overheated that we are initially waiting for, which refutes a long -standing theory of the 1980s”, author of the study Thomas WhiteAssociate professor of physics at the University of Nevada, said Reno in the press release.

In relation: Scientists identify the water molecules turning away before separating, and this could help them produce cheaper hydrogen fuel

The solid gold sample reached a laminate of 19,000 kelvins (33,700 degrees Fahrenheit, or 18,700 degrees Celsius) – 14 times the standard melting point of the element of 1,337 Kelvins (1,947 F, or 1064 C). “It may be the hottest crystalline material ever recorded,” added White in another statement. “I expected gold heating up quite considerably before melting, but I did not expect an increase in temperature fourteen times!”

Normally, solids and liquids have a defined temperature to which they change from one state to another. But under certain conditions, the materials can be heated beyond these limits without changing the state – a phenomenon called overheating. This effect is sometimes observed in heated water in the microwave. If the container is smooth, there are no irregularities around which the bubbles can form so that the liquid water bypass 212 F (100 C) without boiling. However, the slightest disturbance can trigger the “disaster” and the water bouillon explosively as this metastable state is broken.

In the 1980s, physicists calculated the limit of this overheating effect for solids as three times the melting point, which they nicknamed the “Entropy Catastrophe”. Above this point, the solid would theoretically have greater entropy, or disorder, that its liquid form, breaking the Second thermodynamic law. As this law indicates that entropy must always increase, the idea that particles carefully arranged with a solid could be more disorderly than the random distribution of particles in a liquid is an impossible contradiction.

So how did the gold sample remain solid at 14 times its melting point? The team suggested that the pure speed they heated gold prevented the crystal structure from developing during the time scale of the experience.

“It is important to specify that we have not violated the second law of thermodynamics,” said White. “What we have shown is that these disasters can be avoided if the materials are heated extremely quickly – in our case, in billions of dollars of a second.”