Scientists invent way to use E. coli to create and dye rainbow-colored fabric in the lab

Scientists used genetically modified bacteria to simultaneously create and stain tissues in a one-pot method. Compared to current methods that rely on fossil fuels, the new technique offers a simpler and more sustainable way to produce colorful textiles.

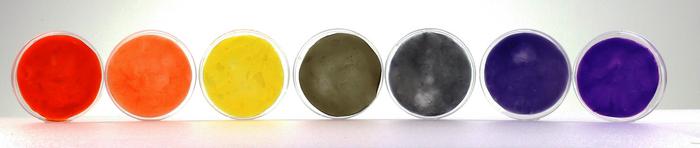

In a new study described November 12 in the journal Trends in biotechnologyresearchers created cellulose-based fabrics spanning the colors of the rainbow by changing the conditions used to grow the bacteria.

Therefore, in recent years there has been a growing trend to use an alternative method of producing natural fibers from the fermentation of bacteria. Cellulose is a promising target because the material mimics natural fibers found in fabrics like cotton. A wide range of bacteria typically convert glucose into cellulose fibers to provide structural support and defend against other microbes. However, the cellulose produced by bacteria is naturally white, meaning it often needs to be dyed after processing.

Lee and his team have now simplified this process by growing cellulose-producing bacteria alongside microbes that produce natural dyes. The team used color-producing plant strains Escherichia coli (E.coli) to create two classes of dyes: the darker violaceins (which produced colors such as purple, blue, and green) and the warmer carotenoids (which produced colors such as red, orange, and yellow).

First, the researchers genetically modified the metabolic pathway of a strain of Komagataeibacter xylinus bacteria to increase cellulose production during fermentation. Then adding the violacea producer E.coli in the reaction vessel yielded fabric dyed purple, blue and green.

However, the team could not use the same method to achieve warmer tones because the bacteria did not produce enough dye to stain the cellulose fabric, likely due to poor bacterial growth. To overcome this problem, they added pre-cultured and processed cellulose to a culture of carotenoid-producing cells. E.coli. This co-cultivation method resulted in fabrics dyed red, orange and yellow, complementing the team’s rainbow palette.

Overall, this method “eliminates the need for separate dyeing and washing processes,” Lee said, adding that this helps reduce chemical waste and water consumption.

Colored bacterial cellulose showed strong overall stability against acids, bases, heat treatments and washing. However, the team noted that further work is needed to fully test these materials, including to verify their durability against industrial detergents and mechanical wear.

In the future, Lee wants to “expand the current seven-color platform to a broader spectrum” and expand the process to an industrial level while maintaining consistent quality. Further changing the way bacteria produce cellulose could pave the way for other uses of the material, such as biodegradable packaging, he said.