Seth Rogen’s Toothless Hollywood Satire

Books & the Arts

/

June 25, 2025

The Studio is pitched as a send-up of the idiocy of the entertainment industry, but its potshots are harmless, even friendly.

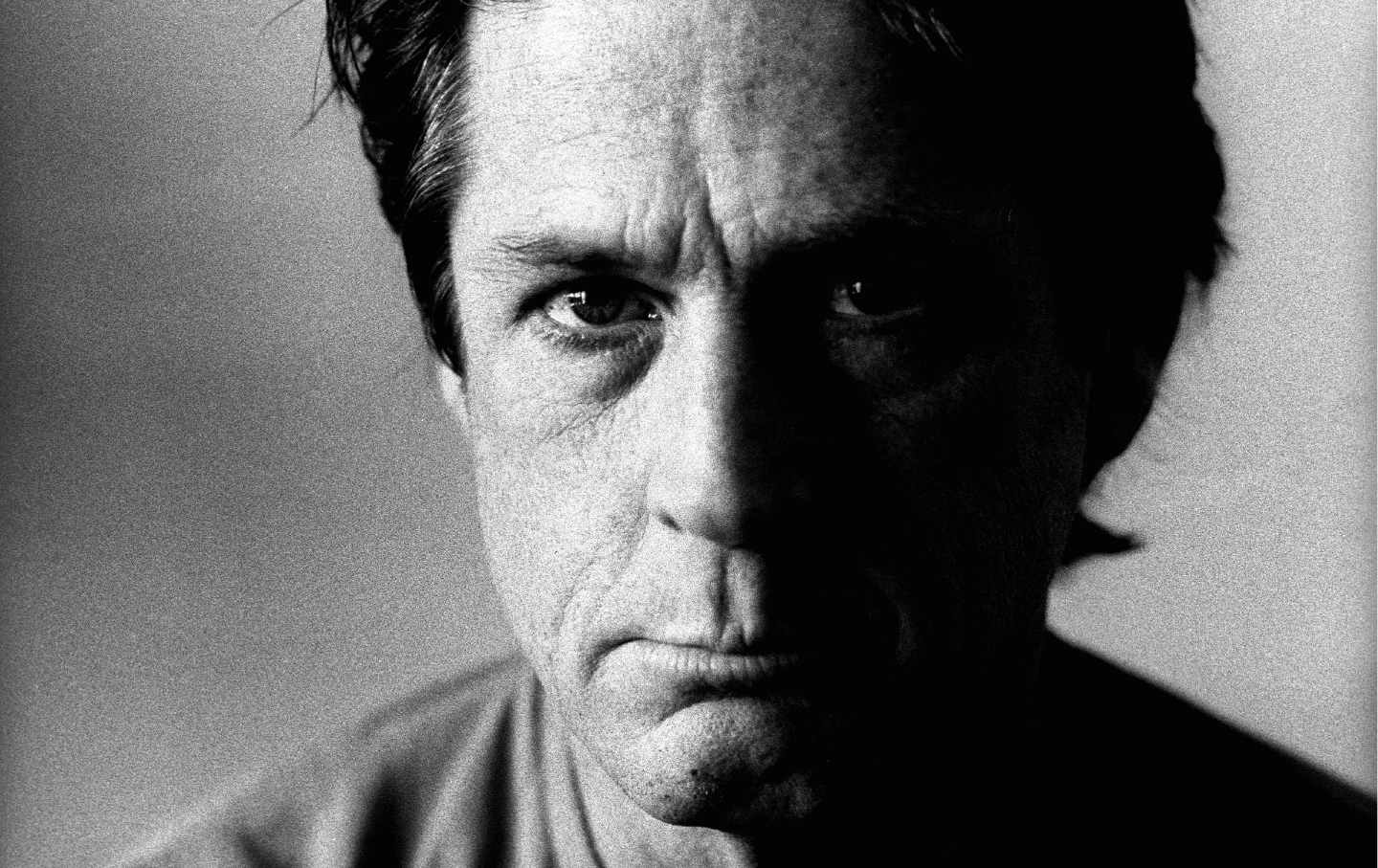

In Robert Altman’s The Player (1992), a studio exec named Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) kills a screenwriter in cold blood. He mistakenly believes his victim was a stalker who had been sending death threats to his office, presumably because he rejected one of his movie ideas. Mill only greenlights 12 pitches every year, and he will only approve those that have certain audience-friendly elements, primarily happy endings. At a glitzy charity gala, Mill gives a self-aggrandizing speech arguing that film studios have “a responsibility to the public to maintain the art of motion pictures as [their] primary mandate.” In reality, though, he will happily sacrifice art on the twin altars of entertainment and capital, and step over anyone who gets in his way.

Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg’s series The Studio, which just wrapped its first season on Apple TV+, pays homage to Altman’s Hollywood satire by featuring a similar but unrelated character also named Griffin Mill (Bryan Cranston), the obnoxious CEO of the fictional Continental Studios, who would never pretend that movies are anything more than disposable assets. In The Player, Mill projects respectability even at his most reckless and philistine, befitting his role as a well-groomed industry gatekeeper; in The Studio, Mill exhibits no politesse when demanding that new studio head Matt Remick (Rogen) reject “artsy-fartsy filmmaking bullshit” in favor of IP-driven projects. “If Warner Bros. can make a billion fucking dollars off the plastic tits of a…doll, we should be able to make two billion off the legacy brand of Kool-Aid,” he crudely and proudly declares about their latest brand acquisition.

At its heart, The Studio is an episodic sitcom. Rogen plays Remick, the show’s protagonist, like a classic schlemiel (only with outsize wealth and influence), someone who repeatedly suffers public humiliation by his own hand in his pursuit of balancing art with the demands of commerce. He falsely promises Martin Scorsese that he’ll fund his final film (about the Jonestown massacre) only to kill it out of shortsighted cowardice, prompting Charlize Theron to boot him from a party. He runs headfirst into an unforced public relations nightmare involving racial casting and artificial intelligence that culminates in a crowd at the Anaheim Comic-Con directing its ire toward him onstage.

As much as the series luxuriates in exaggerated high jinks, The Studio’s insider perspective is its literal raison d’être. Rogen and Goldberg—two industry veterans who have maintained their everyman status—have witnessed and participated in Hollywood’s devolution into a franchise-obsessed shell of its former self. (Rogen especially has worked, for over 20 years, behind and in front of the camera on just about every type of project that Hollywood still makes, from low-brow comedies to comic-book-based actioners.) They are nominally well-suited to comment upon the inner workings of contemporary hackdom.

A well-trodden legacy of biting the hand that feeds has long existed in the entertainment industry—it’s a way for artists to take harmless potshots at benefactors to demonstrate their savvy to audiences while exorcising their guilt and self-loathing for cashing those paychecks. To expect The Studio, which is produced by Lionsgate and distributed by Apple, to draw real blood with its industry criticisms would be foolish. But even under the most measured expectations, the series pulls far too many punches. Altman described The Player as a “very mild satire” that couldn’t really offend anyone in Hollywood, but at least he made his industry protagonist a true villain. Rogen and Goldberg, on the other hand, largely want people to know that everyone in the industry, no matter how venal and self-serving they can be, are basically good at heart.

“Igot into this [business] because I love movies,” Remick ruminates aloud in The Studio’s first episode, “but now I have this fear that my job is to ruin them.” On an episode of The Late Show, Rogen relayed to host Stephen Colbert that he lifted that line from current 20th Century Studios president Steve Asbell, who once said exactly that to him and Goldberg years prior. The Studio has reportedly been pored over on similar grounds by studio executives to determine whether they’re being targeted by the show. According to Rogen, many inaccurately see themselves in certain characters and plotlines.

Inflated egos aside, this type of collective projection is understandable. Most characters in The Studio are amalgamations of people whom Rogen and Goldberg have crossed paths with, but some have obvious real-life inspirations. Mill, for example, is loosely based upon the controversial CEO of Warner Bros., David Zaslav, though he’s costumed to resemble eccentric Hollywood producer Robert Evans. Meanwhile, Remick’s mentor Patty (Catherine O’Hara) exhibits shades of producer Amy Pascal—who currently runs Pascal Pictures and was previously cochairwoman of Sony Pictures, until she was fired for numerous racially insensitive comments uncovered during the 2014 Sony Pictures hack.

Similarly, some storylines are loosely based upon real events. In the show’s second episode, Remick ruins an expensive, elaborate long take on one of his productions by trying to be overly ingratiating toward director Sarah Polley and lead actress Greta Lee. That plot was taken and embellished from a story about CBS Films’ then-COO Wolfgang Hammer interrupting a shot during the filming of Seven Psychopaths because he was trying to talk to costar Woody Harrelson. The episode in which Remick desperately tries to convince Zoë Kravitz to thank him in her Golden Globes acceptance speech stems from an unnamed executive’s alleged devastation after not being acknowledged when one of Rogen and Goldberg’s films won a Globe. (By all accounts, the award in question would have to be James Franco’s Best Actor win for The Disaster Artist, which was distributed and funded by A24 and Warner.)

The Studio ensures that film workers on all rungs of the ladder can find real-world analogues in any given episode. (Longtime producer Scott Macaulay has said that the show’s third episode, about Remick and his fellow execs struggling to tell Ron Howard to cut a terrible sequence from his new film, rings especially true with his own experiences giving feedback.) But even the show’s best ripped-from-the-back-lot process stories reek of self-flattery, because Rogen and Goldberg bemoan and celebrate the industry in equal measure. Remick—a self-proclaimed cinephile, which basically means that he’s familiar with Goodfellas and Chinatown—takes it upon himself to keep Continental Studios, and cinema itself, alive at all costs. In order to do that, however, he must retain his job as studio head, which often means selling out the art form bit by little bit. The Studio tries to convey the comedy and tragedy embedded in such a professional bind, but it has a muted impact because the show shies away from condemning any of the forces responsible for Remick’s quandary. Case in point: The Studio initially treats the Kool-Aid Man movie that Remick has been pressured to produce as the absurd, soulless embodiment of everything wrong with contemporary Hollywood. That existential urgency eventually abates, however, and it becomes just another stupid project.

During a panel discussion, Rogen claimed that The Studio was written from the perspective of people who love the industry but find it “fucking frustrating and aggravating” because they’re “constantly seeing people make choices that are confounding and contrary to their own love of film.” That frustration comes through as a resigned, if not indifferent, acceptance of that very situation, largely because Rogen and Goldberg have far too much affection for their characters. Rogen’s fellow executives in the show—from Ike Barinholtz’s loose-lipped, coke-snorting VP of Production to Chase Sui Wonders, who plays a junior exec who believes she arrived “30 years too late to this fucking industry”—are all depicted as people doing their best with the hand they’ve been dealt instead of willing (if conflicted) collaborators. Maybe that would translate better if The Studio committed to having some kind of antagonist, but the closest it comes to one is Mill, and by season’s end, he’s basically a clown instead of a devil.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Even the myriad cameos by A-listers, all of whom are transparently self-conscious of the public personas that the show will send up, feel vetted to ensure that no one looks too bad: Olivia Wilde intimidates the cast of her new directorial effort, Ron Howard screams profanity, Dave Franco gets high, etc. The most egregious guest turn comes from Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos, who explains to Remick in the bathroom during the Golden Globes that he contractually mandates that anyone from his slate who wins an award must thank him onstage. “We’re bean counters, they’re artists,” he says with a slimy wink. The appearance of self-awareness about his place in the industry comes off as immediately insincere: Sarandos has publicly argued that the theatrical distribution model his company has worked tirelessly to undermine is simply outdated. But Rogen makes sure to defend him: “I’ve known [Sarandos] for a really long time,” he told Vanity Fair. “I know he’s a real fan of movies.”

Meanwhile, Remick’s internal struggle on art versus commerce eventually devolves into ordinary insecurity about, well, everything. The show’s best, most frustrating episode involves his relationship with Sarah (Rebecca Hall), a pediatric oncologist largely unfamiliar with show business and the nature of his job. She invites him to a Cedars-Sinai fundraiser, where he hobnobs with a group of condescending doctors who look down on Remick and the very act of moviegoing. They parrot a host of familiar talking points: that they stopped going to the movies after Covid (save for Barbie and Oppenheimer); that cinemas pale in comparison to their own home theater setups; and that contemporary film is all “superheroes and fighter pilots.”

Remick’s rage over being disrespected steadily rises over the course of the episode, and he eventually tanks the fundraiser and ends his relationship in a spectacularly uncomfortable fashion. But while the doctors, caricatured to be as arrogant and uncool as possible, make supposedly blinkered, patronizing claims, The Studio takes their wrongness for granted. And this despite the fact that Remick’s proudest achievement at Continental involves shepherding an action franchise about a guy who can blow things up with his mind—and that during the fundraiser, he’s reviewing cuts on his phone of a trailer for Duhpocalypse!, a postapocalyptic film featuring zombies who infect people with their diarrhea that Remick argues is a satire about medical disinformation.

Obviously, Rogen and Goldberg are aware of the irony at play when Remick claims that his job marshaling these low-brow works into theaters is every bit as important as treating children with cancer. But it’s also possible that they’ve spent so much time in the belly of the beast that they can’t begin to see their own real point: that the standards for the average Hollywood film have fallen so precipitously that they’re making the case for their own obsolescence. Remick’s admirably populist belief that “all movies are art” has become such a cultural shibboleth that meaningful quality standards no longer exist. “So, Picasso’s Guernica and The Emoji Movie are both art?” Sarah counters skeptically. It’s telling that Remick evades her question entirely.

Whether the major studios are really making art also lies at the core of The Player. If every movie needs to be focus-group-tested within an inch of its life to ensure its commercial appeal, and if no one in power wants to take a creative risk, then what separates a movie studio from any other corporate entity? While Altman’s film predicted our vulgar present, it was firmly ensconced in a 20th-century film culture that had awareness and respect for its own history. Though The Player takes shots at Hollywood’s obsession with sequels and its mindless dependence on elevator pitches (e.g., “Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman”), it’s painfully revealing that, with 30 years of hindsight, the movie’s vision of sell-out, mainstream detritus still resembles an actual film instead of mere “content.” When The Player’s Mill muses sarcastically about eliminating writers, actors, and directors from the filmmaking process, it was a laughably far-fetched idea. But with the industry’s burgeoning AI obsession, that could now be a potentially achievable goal.

The Player revitalized Altman’s career after he spent more than a decade in the wilderness making high-profile commercial flops. Altman channeled that earned resentment into his comeback because he witnessed the industry’s mandates changing in real time after he came to prominence in the 1970s when he helped alter the American film landscape with films like M*A*S*H and Nashville. Rogen and Goldberg, on the other hand, are victors instead of underdogs, two writers who have emerged from the industry’s trenches mostly unscathed. That doesn’t mean their perspective lacks value—on the contrary, it provides them with genuine expertise—but it indicates a certain aversion to landing a clean, hard punch. The Studio’s first season ends with a large crowd of CinemaCon attendees enthusiastically chanting, “Movies! Movies! Movies!” Rogen and Goldberg’s awareness of the irony that such loud (albeit facile) passion for cinema exists only on TV resides firmly on the show’s surface. But while they can diagnose cultural problems all day, they show little interest in addressing the underlying rot.

Every day, The Nation exposes the administration’s unchecked and reckless abuses of power through clear-eyed, uncompromising independent journalism—the kind of journalism that holds the powerful to account and helps build alternatives to the world we live in now.

We have just the right people to confront this moment. Speaking on Democracy Now!, Nation DC Bureau chief Chris Lehmann translated the complex terms of the budget bill into the plain truth, describing it as “the single largest upward redistribution of wealth effectuated by any piece of legislation in our history.” In the pages of the June print issue and on The Nation Podcast, Jacob Silverman dove deep into how crypto has captured American campaign finance, revealing that it was the top donor in the 2024 elections as an industry and won nearly every race it supported.

This is all in addition to The Nation’s exceptional coverage of matters of war and peace, the courts, reproductive justice, climate, immigration, healthcare, and much more.

Our 160-year history of sounding the alarm on presidential overreach and the persecution of dissent has prepared us for this moment. 2025 marks a new chapter in this history, and we need you to be part of it.

We’re aiming to raise $20,000 during our June Fundraising Campaign to fund our change-making reporting and analysis. Stand for bold, independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

A conversation with the German sociologist about the challenges that face Europe and his polarizing views on how to roll back the excesses of globalization.

Books & the Arts

/

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

When the Beach Boys front man died, the obituaries described him as a genius. Which means what, exactly?

Sid Holt

The show is at once a succession story, a riches-to-rags tale, and a buddy comedy about two hapless brothers trying to save their father’s convenience-store empire.

Books & the Arts

/

Jorge Cotte