Snails and Sediments Reveal the True Age of a Site Occupied By Ancient Humans Who Left Africa

An archaeological site in the Middle East today constitutes one of the oldest areas occupied by humans outside of Africa, a distinction etched in stone by snails and ancient sediments. The Ubeidiya site, located just south of the Sea of Galilee in the Jordan Valley, has been given a revised date that dates back to 1.9 million years ago.

A new study published in Scientific reviews of the Quaternary confirmed that Ubeidiya contains the oldest evidence of early humans outside of Africa, along with the site of Dmanisi in the Georgian nation. Various dating techniques have revealed that ‘Ubeidiya is hundreds of thousands of years older than previously thought, rewriting the turning point in history when the first humans began traveling to unknown lands.

Learn more: 2 million-year-old skeleton shows early humans were still built for trees

Migrate to new territories

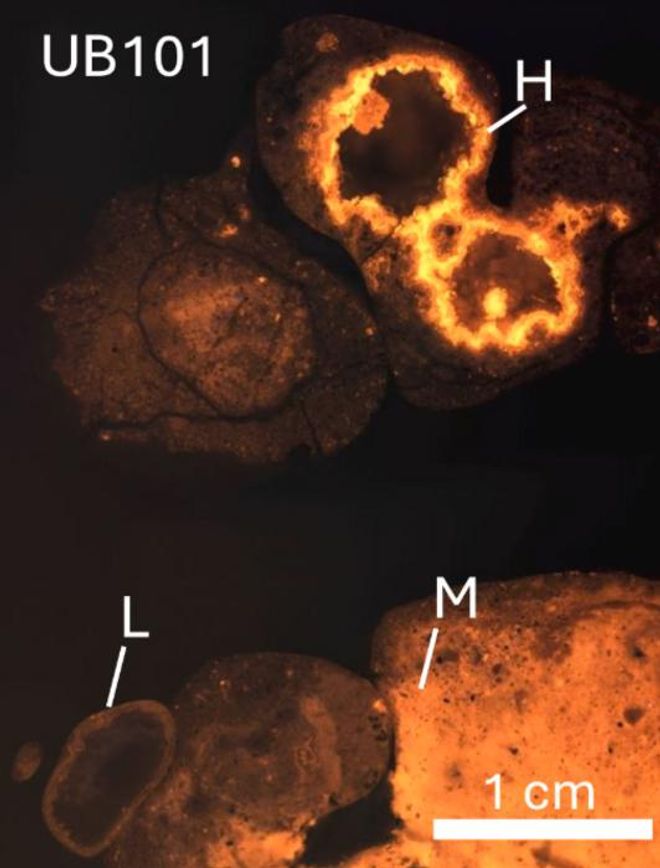

Mineral layers preserved in a fossilized shell.

(Image credit: Perach Nuriel)

The ancestors of modern humans are believed to have emigrated from Africa around 2 million years ago and gradually spread throughout Eurasia. Archaeologists have explored various sites that bear witness to the first human occupations.

The medieval Georgian town of Dmanisi, for example, is home to a site dating back around 1.8 million years ago. This site contains approximately 100 ancient human fossils, more than 8,000 animal remains and more than 11,000 stones and stone objects, according to the International Commission on Geoheritage.

‘Ubeidiya is another important prehistoric site that was occupied by early humans who left behind large bifacial stone tools that are part of the Acheulean culture (often associated with Homo erectus individuals who made pear-shaped axes). However, establishing the exact age of Ubeidiya has been a challenge for archaeologists, according to a statement on the new study.

Previous estimates dated the site to between 1.2 and 1.6 million years ago, but these were acquired through relative chronology; this method only arranges specimens chronologically without determining their actual ages, according to the American Museum of Natural History.

Sediment and Snail Survey

To determine a definitive age range for ‘Ubeidiya, researchers involved in the new study used three dating methods capable of providing more precise measurements than relative chronology. These methods relied on various aspects of the site’s sediments.

“Precise dating of sediment burial in a sedimentary basin is highly dependent on understanding the history of the sediments prior to burial, recognizing sediment sources, and understanding sediment recycling,” the researchers wrote in the study.

Using a method known as cosmogenic isotope dating, researchers measured rare isotopes hidden in ancient rocks. Because isotopes decay at a predictable rate over time, they essentially act like a geologic clock that tells how long rocks have been underground.

Another method allowed researchers to examine traces of the Earth’s ancient magnetic field in the site’s sediments. The sediments contain a record of the direction of the magnetic field at a given time, which the researchers compared to known reversals of magnetic polarity throughout the planet’s history. With this method, they discovered that the Ubeidiya sediment layers formed during the Matuyama Chron, a geological time interval that occurred more than 2 million years ago.

In addition to isotopes and magnetic indices, researchers have also turned to Melanopsis fossilized snail shells in sediments. They used uranium-lead dating on the shells to establish the age of the layers where the stone tools were found.

A range of prehistoric tools

These three methods helped the researchers reach a conclusion about the age of Ubeidiya: the site is now considered to be at least 1.9 million years old, roughly the same age as the Dmanisi site.

Although they are similar in age according to the new study, Dmanisi and ‘Ubeidiya have an interesting difference: ‘Ubeidiya contains the aforementioned Acheulean tools, but Dmanisi contains Oldowan tools, an older technology created by Homo habilis (an ancestor of H. erectus).

This suggests that different groups of hominids, each with their own type of stone tools, spread into distinct regions outside of Africa simultaneously.

Learn more: Gigantic blobs of hot rock have impacted the Earth’s magnetic field for more than 200 million years

Article sources

Our Discovermagazine.com editors use peer-reviewed research and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review the articles for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. See the sources used below for this article: