The Enduring Lessons of Wages for Housework

Books & the Arts

/

July 22, 2025

Emily Callaci’s history of the international feminist movement examines the influence of their intellectual and political victories.

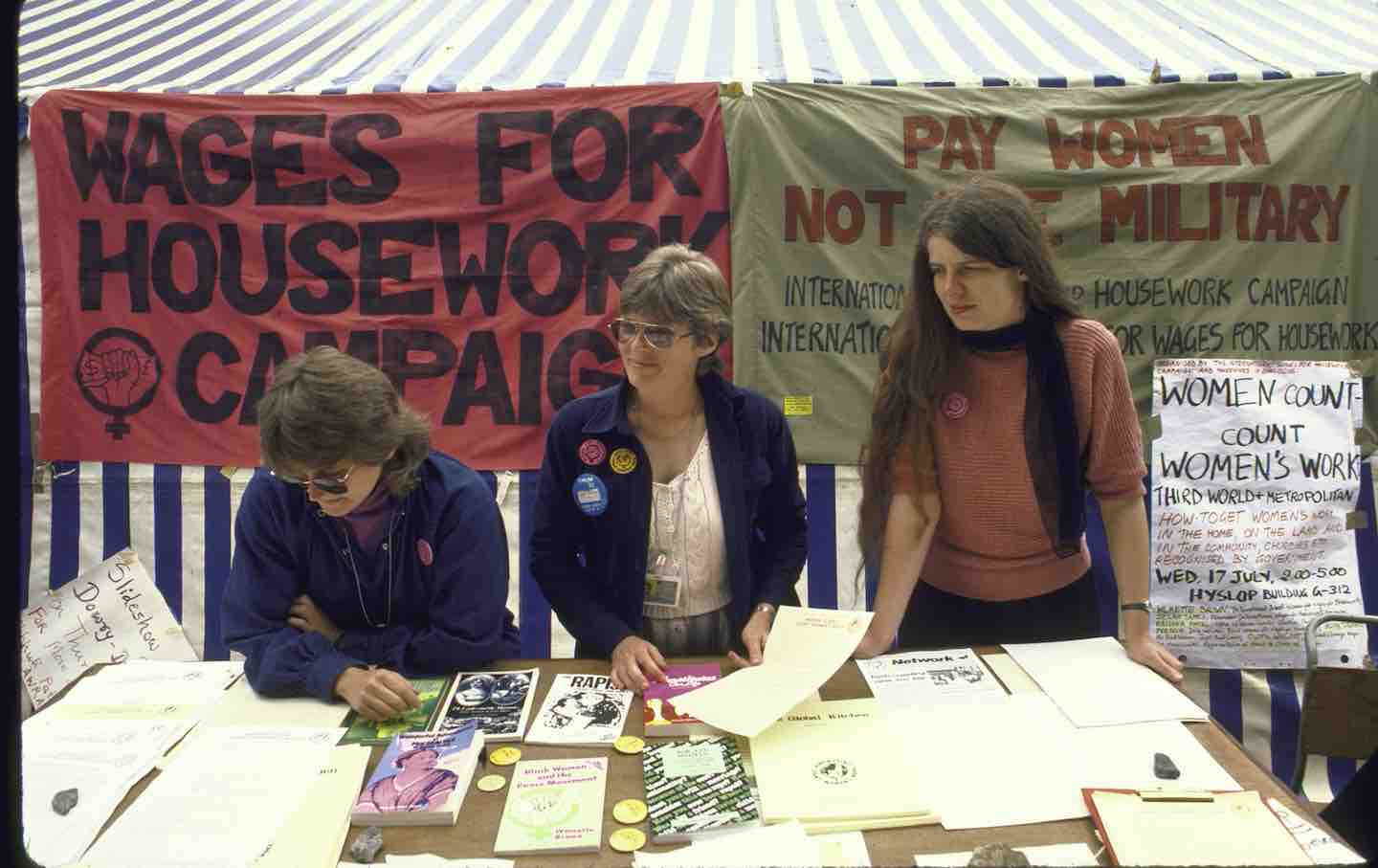

Three members of Wages for Housework Association at literature table at Forum 1985, a women’s conference in Nairobi.

(William F. Campbell / Getty Images)

On February 14, 1974, a group called the Power of Women Collective convened a meeting in Kilburn, London, on the topic of “Living Through the Crisis.” Four months earlier, Middle Eastern oil exporters had established a total embargo against countries that supported Israel during its 1973 war against Arab nations. In the United Kingdom, where labor unrest in the coal industry exacerbated the effects of the resulting global fuel shortage, Prime Minister Edward Heath declared a state of emergency. Refusing to negotiate with the miners, who demanded higher wages as prices soared, Heath’s Conservative government mandated a three-day workweek for all nonessential businesses and ordered households to limit heating to a single room. During periodic blackouts through the winter, Brits read by candlelight and shivered under blankets. Despite these draconian measures, oil prices continued to surge, and at the end of January 1974, the National Union of Mineworkers voted to go on strike.

Books in review

Wages for Housework: The Feminist Fight Against Unpaid Labor

Buy this book

But this was not the “crisis” to which the Power of Women Collective referred. The real state of emergency, the group insisted, did not result from the embargo or the strike. “This crisis is not about switching something off,” the collective explained in a pamphlet advertising the meeting. “It’s about the extra work it takes to get by on less money, the extra work we have to do when husbands and children are home more.” And while recent events had brought this crisis of domestic labor into the open, it was nothing new. “Even in ‘normal’ times,” the collective declared, “prices are a crisis, rent money is a crisis, bringing up children is a crisis, depending on a man is a crisis.”

Rose Craig, one of several participants from Northern Ireland, recalled getting shot at by British soldiers while transporting a neighbor to a hospital in the Protestant section of Belfast. Craig saw a parallel between the British government’s threat to cut off aid for the miners’ wives and its denial of welfare to Irish women whose husbands were wanted by the police. She suggested that the miners’ wives borrow a tactic from Belfast. “Whenever the National Assistance, or the Social Security as youse call it here, was stopped, the women brought the children down and told the government: You look after the children, we can’t,” Craig told the crowd, to cheers. If a miners’ strike can cause a state of emergency, see what happens when women refuse to do their work.

In fact, some striking miners’ wives in Rugeley, near Birmingham, had already done something like this: bringing their children to the local Social Security office and protesting outside it until the government rescinded a policy that had reduced the amount of their aid. When a new Labour government agreed to raise the miners’ wages and ended the state of emergency in March of 1974, such actions were not credited. But as the University of Wisconsin–Madison historian Emily Callaci describes in Wages for Housework: The Feminist Fight Against Unpaid Labor, these modes of protest were part of an emerging, dynamic wave of left-feminist activism. The Power of Women Collective, which later became London’s Wages for Housework campaign, was one of several organizations across Europe and North America that insisted on the value of women’s unpaid labor in order to protest the welfare cuts, rent hikes, and austerity budgets then being imposed by Western governments.

Largely relegated to the margins of feminist history since the 1970s, the Wages for Housework campaign has experienced a surprising resurgence in popularity in recent years. Since the 2010s, political theorists such as Katrina Forrester, Sophie Lewis, and Kathi Weeks have drawn on Wages for Housework for its contributions to feminist thought and its insights into the nature of work and care in contemporary society. Then, there was the Covid-19 pandemic: a “crisis,” like the 1973 oil shock, that exposed the extent to which the public and private sectors rely on unpaid and underpaid household labor to sustain basic social functions. The resurgence of interest in Wages for Housework inspired memes and murals. Silvia Federici, the 83-year-old scholar and founder of the campaign’s New York branch, was profiled by The New York Times.

Callaci’s book marks a significant contribution to the new Wages for Housework literature and serves as a reminder of the campaign’s true aims. Weaving together capsule biographies of five of its founders, it offers a history that reflects Wages for Housework’s global scope and radical ambitions. When they demanded wages for housework, these activists did not merely assert the importance of domestic labor: They sought to transform those tasks (cleaning, childcare, and the like) into levers of power, wielded not only to advance women’s own status but to alter the political and economic systems that depended on their labor.

Current Issue

Rose Craig had implored her audience to imagine what would happen if one woman on every street in every village brought her family to the Social Security office and refused to leave. “You’ll break the government quicker this way,” she said. “They’ll have to give in to you, so they will.”

Callaci begins her account with Selma James, who convened the Power of Women Collective and its subsequent re-formation as London’s Wages for Housework campaign. Born Selma Deitch in 1930, James grew up in Ocean Hill–Brownsville, a working-class Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn. Like many working-class Jews of their day, James’s parents were Communist Party sympathizers active in a range of political causes. Her mother, who had worked in a paper-box factory before having children, organized neighborhood women to demand relief money during the Great Depression. After finishing high school, James married a fellow traveler, moved to Los Angeles, and held jobs in factories and restaurants while working as a left-wing organizer and activist.

In Los Angeles, James joined the Johnson-Forest Tendency, a group founded by the Trinidadian historian and writer C.L.R. James, the Russian-Jewish philosopher Raya Dunayevskaya, and the Chinese-American philosopher Grace Lee Boggs. The Johnson-Forest Tendency rejected the hierarchy of traditional political parties, instead aiming to ground theory and action in the lived experiences of ordinary workers. As a member of the Tendency, James published her first political pamphlet, “A Woman’s Place,” in 1953. In it, she challenged the Marxist orthodoxy that organizing women would require bringing them out of isolated households and into the factories. Women could be organized in the household, she argued, because they were already organized there: Housewives boycotted stores that hiked prices, barricaded streets to create safe places for children to play, and picketed against the companies that emitted toxic fumes into the air. “A Woman’s Place” was the most popular pamphlet that the Tendency had ever published.

Selma became romantically involved with C.L.R. James and divorced her husband. Threatened with deportation for his political activities, James moved to London in 1953, and Selma joined him there two years later and married him. In London as well as on trips to the West Indies, the couple became deeply involved in anti-colonial and anti-racist struggles. But the Jameses’ genuine partnership as activists and intellectuals gave way to more traditional gendered roles in the home. Selma did the housework and helped her husband prepare his manuscripts, and she often financially supported him as a factory worker and typist. It was not until the late 1960s, when her son (from her first marriage) went to college and her husband began spending more time abroad, that she finally returned to her own writing and the questions that had preoccupied her when she wrote “A Woman’s Place.”

The second phase of Selma James’s career coincided with the burgeoning of London’s women’s movement. But James often felt ill at ease with that movement’s narrow focus on the problems of white, professional women. Still, it was in a women’s liberation workshop in Notting Hill that she found a kindred spirit in the Italian political scientist Mariarosa Dalla Costa. As Callaci recounts, Dalla Costa received her political education from an Italian movement, Operismo, whose focus on worker autonomy resembled that of the Johnson-Forest Tendency. Dalla Costa, like James, felt caught between Marxists who made little place for “women’s issues”—and who often relegated the women themselves to supportive roles in the movement—and the failure of the women’s movement to engage with the class struggle and racism. The two women began corresponding and visiting each other regularly, expressing their frustrations and beginning to map out a theory of how women fit into the capitalist system and the project of dismantling it.

In the fall of 1971, Dalla Costa drafted an essay, “Women and the Subversion of the Community,” which was published a year later alongside an Italian translation of James’s “A Woman’s Place” as a book titled Potere femminile e sovversione sociale. Dalla Costa’s essay took aim at an idea at the core of Marx’s understanding of capitalism: the wage relationship. In Capital, Marx had argued that capitalists generated profit, or “surplus value,” by paying workers a wage that amounted to less than the value of the commodities they produced. Because women who worked in the home did not produce commodities for a wage, they did not generate surplus value, and therefore they were not directly subject to exploitation under capitalism. But Dalla Costa argued that women did produce a commodity, the most essential commodity of all: the worker himself. The worker could only labor in a factory because of the women who fed him, clothed him, educated him, and sexually serviced him at home.

Because they were unpaid, these tasks appeared like acts of service. But their benefits were still reaped by the capitalist system. “The figure of the boss is concealed behind that of the husband,” Dalla Costa wrote. In contrast to the assumptions of both liberal feminists and orthodox Marxists, Dalla Costa argued that women’s emancipation wouldn’t come from exchanging one form of exploitative labor for another: “Slavery to an assembly line” was not “a liberation from slavery to a kitchen sink.”

Some critics of Wages for Housework—liberals and leftists alike—simply doubted that cleaning and caring really were forms of labor, or worried that assigning a monetary value to housework would degrade its nonmarket worth. And even other socialist feminists worried that attaching a wage to housework would reinforce, rather than challenge, traditional gendered roles. The most compelling version of this critique came from Black feminists such as Angela Davis, who pointed out in her essay “The Approaching Obsolescence of Housework” that Black women had long performed housework for a wage—and hardly found it empowering.

In her research, Callaci found that Dalla Costa’s initial Italian version of “Women and the Subversion of the Community” warned against establishing “wages for housework” precisely because it risked entrenching women’s subordinate role. But when James and Dalla Costa published an English version of their writings as The Power of Women and Subversion of the Community in the fall of 1972, James added a footnote to Dalla Costa’s essay explaining that those concerns had been dispelled. She clarified that the wage was not an end in itself, but rather “a basis, a perspective from which to start.” The wage was a means of making housework visible as labor: of transforming it into something that could be contested and, ultimately, refused. If the basic premise of capitalism’s structure was the division of waged and unwaged work, then demanding pay for housework would disturb that structure; it would subvert the logic that sustained the exploitation of paid workers, too. When James and Dalla Costa promoted The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community on a speaking tour across North America in 1973, James increasingly did so under the banner of Wages for Housework. (Dalla Costa and James have subsequently disputed whether the essay was solely written by Dalla Costa or coauthored by both women).

Many Wages for Housework texts deploy a similar rhetorical move: identifying tropes of ordinary domestic life and redescribing them in cheekily Marxist terms. “May Day or Mother’s Day?” one flyer asked, proposing a day of revolutionary struggle as an alternative to a holiday that glorified household work. “Women unite. We have nothing to lose but millions of sinks, millions of mops, millions of diapers.” Such wordplay had a purpose: It defamiliarized the actions and objects that most people saw as banal; it politicized the apparently apolitical.

Callaci’s third subject, Silvia Federici, mastered this device. An Italian-born philosopher, Federici moved to the United States to pursue her PhD and soon became active in feminist and anti-racist organizing in New York. After reading “Women and the Subversion of the Community,” she briefly returned to Italy and helped James and Dalla Costa form the International Feminist Collective in Padua in the summer of 1972. Back in the United States, Federici founded the New York Wages for Housework Committee in 1974. She opened her 1975 treatise “Wages Against Housework” with these lines:

They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.

They call it frigidity. We call it absenteeism.

Every miscarriage is a work accident.

There was an element of playfulness—even campiness—in the campaign’s style. Illustrations on leaflets depicted the Statue of Liberty carrying a broom; newsletters heralded the formation of new campaign chapters under the heading “Birth announcement!” (The New York Committee abandoned a plan to dress the actual Statue of Liberty in an apron.) But the underlying point was serious: Federici and her comrades believed that housework—paid and unpaid—was trapped in the realm of love and sentiment. So long as cleaning and care were identified as women’s natural capacities, they were impossible to refuse. To identify these tasks as labor was to bring them into the realm of struggle.

By identifying housework as labor, Wages for Housework also sought to find a framework that might bridge divisions between women. Frustrated with liberal feminism’s elevation of the concerns of predominantly white “career” women above those of their working-class and racialized sisters, the UK campaign took inspiration from the Claimants Union, single mothers who organized to protest cuts to the Family Allowance. Whether they were married or single, straight or gay, had paid jobs or not, all women performed the essential labor that made society’s functioning possible. In the day-to-day of movement organizing, as Callaci observes, solidaristic ideals were not always upheld perfectly. But at its most ambitious, the aim of Wages for Housework was to identify a perspective that would unite all women in a shared class struggle.

The Wages for Housework campaign emerged in the mid-1970s as governments across the West made drastic cuts to social services in the name of fiscal responsibility. The UK’s three-day workweek and reduction of the Family Allowance were matched, on the other side of the Atlantic, by calls to purge the welfare rolls and defund public institutions to balance government budgets. So-called austerity politics reached their peak during New York’s 1975 fiscal crisis, when the city shut down a number of public schools, ended free tuition at the City University of New York, and laid off thousands of sanitation workers. In Park Slope, where the movement’s New York Committee had its headquarters, residents piled their trash in the middle of the street in protest.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Mayor Abe Beame and other local politicians encouraged New Yorkers to volunteer to perform civic services rather than wait for federal aid. But as Callaci recounts, women were already doing the city’s work: watching the children whose schools and daycares had been shuttered, taking care of the sick shut out of hospitals, and repairing the buildings neglected by private landlords. Women’s unpaid labor served as a welfare state of last resort. To recognize this was not merely to understand the gendered logic of austerity; it was to identify a strategic position from which to challenge it. Wages for Housework saw women’s labor as a kind of choke point in the supply chain of basic survival. Even amid the layoffs and wage stagnation of the mid-1970s, unpaid women were occupied with full-time work. There was power where it seemed there was none.

Wages for Housework exercised that power, and often won. While the campaign was sometimes criticized as overly abstract, Callaci shows that its adherents spent much of their time engaged in concrete, material struggles: waging rent strikes, protesting welfare cuts, and lobbying for community-run childcare facilities.

One of Callaci’s major contributions in this book is her account of the activism of Wilmette Brown and Margaret Prescod. Though they have received significantly less attention than James, Dalla Costa, and Federici, Brown and Prescod brought Wages for Housework decisively into alliance with civil-rights, welfare-rights, and anti-colonial campaigns. Brown was a Newark, New Jersey–born activist and academic who had worked with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Black Panther Party. Prescod, who grew up in Barbados, was a member of the African-American Teachers Association in Ocean Hill–Brownsville during the struggle over the school district’s integration in the 1960s. The two women met as faculty at the City University of New York (CUNY), Queens, where they successfully lobbied for a state law that preserved students’ access to welfare benefits. They began attending meetings of the New York Wages for Housework Committee and in 1976 founded their own group, Black Women for Wages for Housework.

Travelling across Europe and the United States, Brown and Prescod pushed the international Wages for Housework movement to engage in new areas of activism. Identifying Black women’s care for the victims of police violence, incarceration, and toxic pollution as labor, Callaci writes, Brown and Prescod “took on James and Dalla Costa’s analysis of how capitalism extracts profit from housework, and turned it over to reveal another side: much of the unpaid work necessary to sustain and protect human life is created by the harms of capitalism.” In this way, Black Women for Wages for Housework made the campaign’s critique of capitalism more global and more urgent.

Callaci narrates the establishment of the 1981 women’s peace camp, which protested the storage of nuclear weapons at Greenham Common in the UK as a culminating battle for Wages for Housework. Brown led one faction of the camp, arguing that Black and brown women bore the burdens of nuclear radiation and war’s other deadly byproducts. She knew this intimately: A year earlier, Brown had been diagnosed with colon cancer, likely connected to her childhood exposure to dioxin, an ingredient in Agent Orange. During the Vietnam War, more than 700,000 gallons of the chemical weapon were produced by a factory in her neighborhood in Newark.

The last of the missiles were removed from Greenham in 1988. By that time, the Wages for Housework campaign had largely dissolved, its organizers divided by issues that were personal, professional, and political. (Callaci makes the wise choice not to get bogged down in these disputes.) But many of Callaci’s subjects have since turned their attention to environmental issues. Dalla Costa began organizing with La Vía Campesina, an international peasants’ movement that campaigns for land reclamation and the restoration of traditional agriculture; Brown has continued to focus on health; and much of Federici’s writing examines the idea of “the commons,” those spaces and resources that might be reclaimed from capitalism and shared by all. Wages for Housework was a campaign of refusal, but it was also, just as crucially, a campaign of “worldmaking”: Its organizers believed that by destroying the most basic pillar of capitalism’s structure, we might create something entirely new in its wake.

Despite its successes, however, Wages for Housework remained on the margins of the women’s movement. As Federici reflected in her 1984 essay “Putting Feminism Back on Its Feet,” women—recognizing that the origins of their oppression lay in the gendered division of labor—were reluctant to be identified as housewives. Instead, they demanded entrance into the paid workforce and equality within it. But they did so without adopting, in Federici’s terms, a “strategic perspective”: a long-term vision of what might replace the old division of labor. So the response to a housewives’ rebellion was not the abolition of housework but its redistribution into the market economy and onto the shoulders of immigrant workers from the Global South.

As Callaci writes, the inherent instability of this “solution” became clear during the Covid-19 pandemic, when much of marketized care work became inaccessible to all but the elite few. Across the political spectrum, the pandemic inspired a renewed focus on women’s unpaid labor: from progressive calls for state-funded childcare to the conservative embrace of “trad wives” and natalism. So it was perhaps no surprise that Wages for Housework re-entered the public discourse at that moment. But as Callaci notes, the movement was sometimes invoked only to lament the career sacrifices of professional women or to elevate the virtues of caregiving. These narrow interpretations shortchange the wide scope of Wages for Housework’s focus and the radical ambition of its demands. They overlook, as Callaci writes, that for the campaign, housework was nothing less than “an Achilles heel in the capitalist system, and a place from which we could organize to overthrow it.”

What’s all too easy to forget, in other words, is strategy. For James, Dalla Costa, Federici, Brown, and Prescod, housework was important first and foremost not because it had any inherent value but because it represented a pressure point in capitalism’s design. This was what Dalla Costa meant by the “subversion of the community,” what Federici called “counterplanning,” and why Brown and Prescod described the campaign as a continuation of the Black freedom struggle. The leaders of Wages for Housework were organizers. Their point was to win.

More from The Nation

In Death Takes Me, an intellectual murder mystery, the Mexican author looks at the overlap between acts of interpretation and acts of violence.

Andrea Penman-Lomeli

From the Cold War till Donald Trump, there’s always been a special dispensation for hawkish bigots.

Jeet Heer

Our art critic visits the Smithsonian American Art Museum to get a closer look at the Trump administration’s attack on DC arts institutions.

Books & the Arts

/

Barry Schwabsky