The Left Has a Hyperpolitics Problem

What gives the book its bite is his reading of “Putnam from the Left.” In Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Rebirth of the American Community (2000), Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam traced how the decline of community groups and civic ties in the United States had produced an atomized political system. For Putnam, writing in the post-political era, history was about civil society itself. He had little interest in the decline of unions, neoliberalism, or the changing characteristics of capitalism. Besides declining voter turnout rates, he has not paid much attention to the decline in party presence on the ground. A commission of personalities under Putnam’s leadership, whose most notable member was an Illinois state senator named Barack Obama, proposed “150 Things You Can Do to Build Social Capital,” among them “Hold a Neighborhood Barbecue” and “Give Your Park a Weather-Proof Checkerboard.”

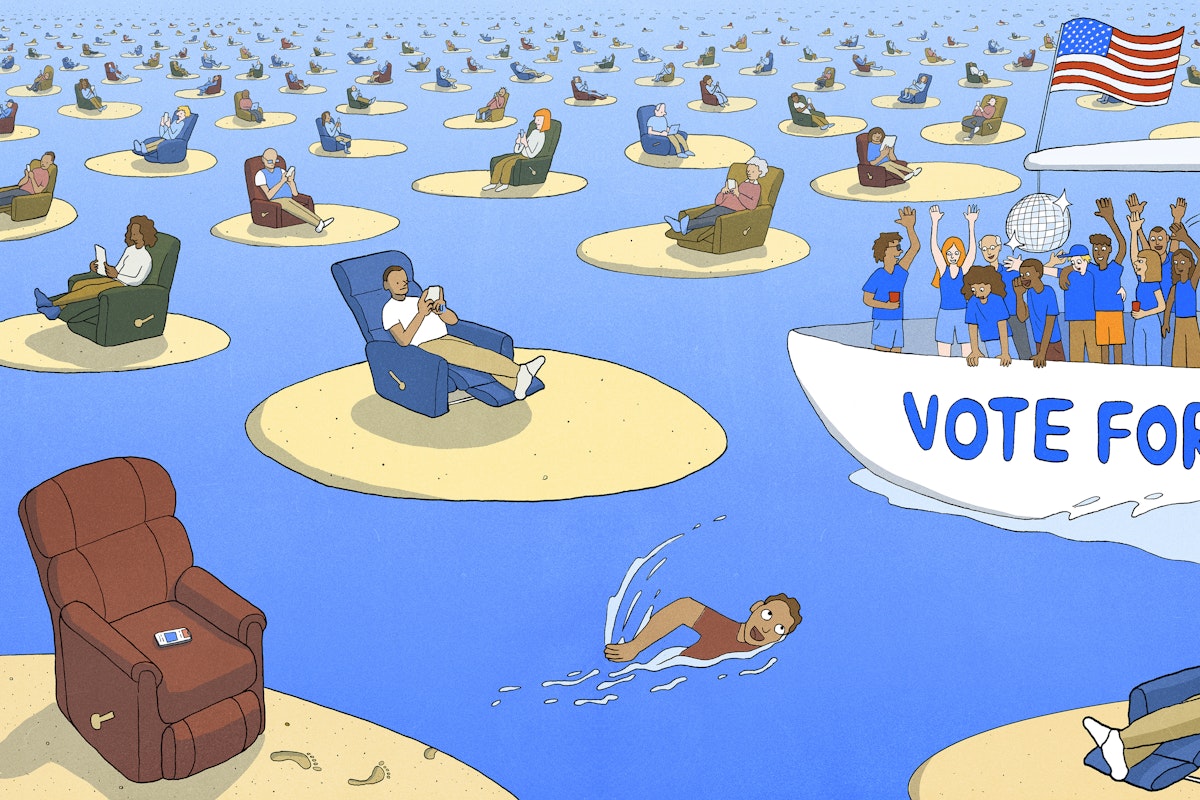

For Jäger, the loosening of social bonds identified by Putnam explains not only the decline of institutionalization, with the erosion of unions and the disappearance of the dense organizational culture around mass parties, but also why increased politicization would fail to register in a sustainable organization, and why it would harm the left. It is not only the story of an endless scroll of clickable content, but also of the “desert of sociability” – a void in place of the associations that had forged political and class consciousness. Jäger cites Hungarian philosopher Gáspár Miklós Tamás’s observation that the “counter-power of the unions and working-class parties” was supported by “their own savings banks, health and pension funds, newspapers, extramural folk academies, workers’ clubs, libraries, choirs, brass bands, engage intellectuals, songs, novels, philosophical treatises, scholarly journals, pamphlets, established local governments, temperance societies – all with their own morals, manners and style. These social worlds formed political loyalties far more solid and enduring than anything offered today outside of a few religious groups, blending deep commitments with ongoing social and community ties.

On one level, this is all just romance, a portal to a vanished world. But it is also a very real entry into contemporary debates. If a cell with high politicization and low institutionalization is bad for left politics and the crises that shake rich democracies lead nowhere, then the only way out is to return to the world of high politicization and high institutionalization of mass politics. Creations of the 19th century, the union and the mass party reached their peak in the 20th and continued into the 21st. As “resources of power,” in the words of the Swedish sociologist Walter Korpi, they remain unrivaled, serving not only as receptacles of social energy but also as shapers of social struggle. All sorts of nonprofits claim to represent the oppressed, but as anyone who’s ever attempted power politics on the left can attest, it’s always the unions that have real connections to their members and also have the strength to get things done. And, love it or hate it, there’s no getting around party politics.