The Top 10 Math Discoveries of 2025

December 19, 2025

3 min read

Add Us On GoogleAdd SciAm

The 10 Biggest Math Breakthroughs of 2025

Hidden Fibonacci numbers, a new shape and the search for a grand unified theory of mathematics are among our choices for most exciting findings of the year

OsakaWayne Studios/Getty Images

This year has seen some amazing advancements in fundamental mathematics. Researchers have made breakthroughs in geometry, topology, chaos theory, and more. And a startling three of our top 10 discoveries involve the perennially fascinating prime numbers.

Without further ado, here are some of the most fascinating math findings Scientific American wrote about in 2025:

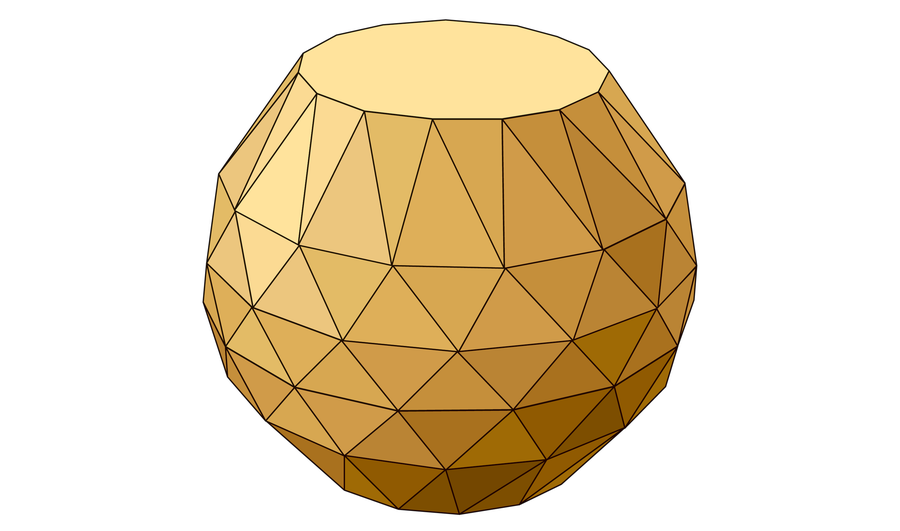

Amanda Montañez; Source: “A Convex Polyhedron without Rupert’s Property,” by Jakob Steininger and Sergey Yurkevich; arxiv.org/abs/2508.18475v1, August 25, 2025 (reference)

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A New Shape

A newfound shape called a noperthedron has 90 vertices, 240 edges and 152 faces. The baroque shape has a surprising property that disproves a long-standing geometrical conjecture: no matter how you shift or rotate it, one noperthedron can’t fall through a straight hole in an identical noperthedron.

Prime Number Patterns

Prime numbers, divisible only by themselves and 1, have long fascinated mathematicians. Discovering new ones is difficult as you get to larger and larger numbers. But this year mathematicians have found a set of probabilistic patterns that govern how the primes are distributed. The patterns involve random chaotic behavior and fractals.

A Grand Unified Theory

A “gargantuan” effort involving nine mathematicians and five papers spanning almost 1,000 pages recently proved the geometric Langlands conjecture. The conjecture connects the properties of different Riemann surfaces, which are structures with coordinates that have real and imaginary parts. It is part of a broader set of problems called the Langlands program, which, if fully proven, could provide a “grand unified theory of mathematics.”

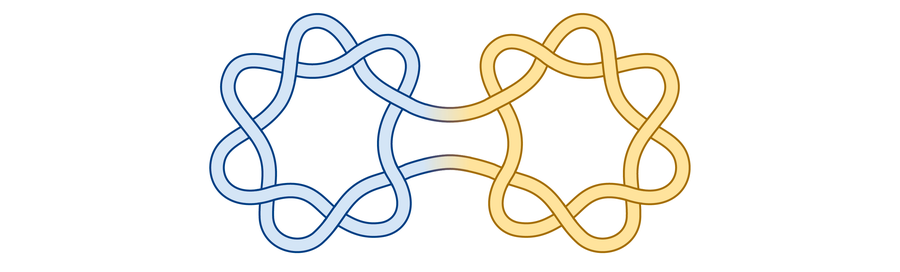

Knot Complexity

A long-standing conjecture stated that if you attach the ends of two different knots to each other, the complexity of the new knot you create will be the sum of the individual knots’ complexity. But the recent discovery of a knot that is simpler than the sum of its parts disproves that assumption.

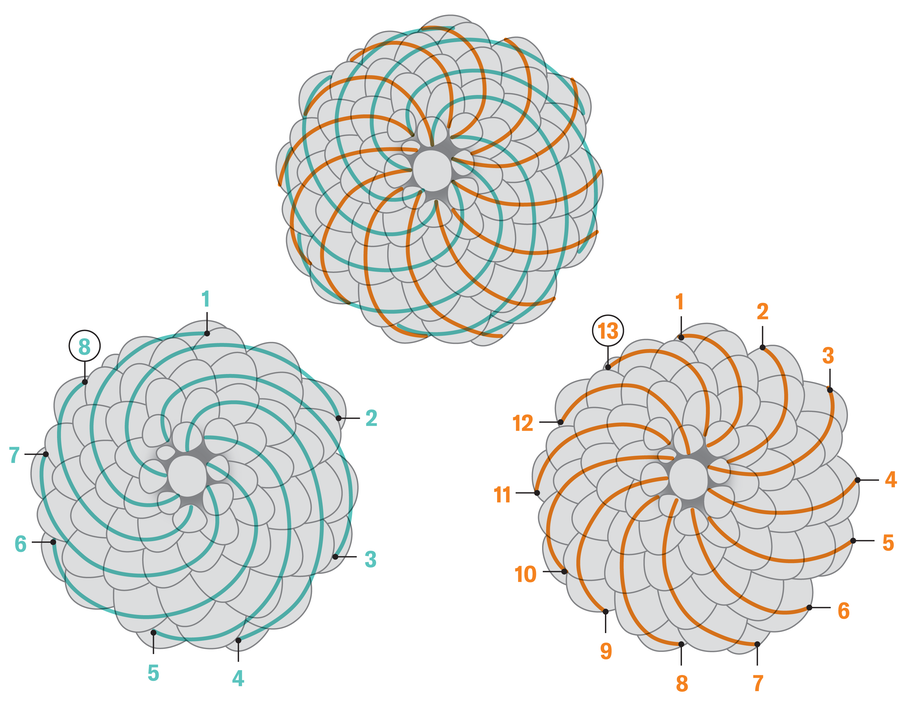

Fibonacci Problems

The Fibonacci sequence, in which each term is the sum of the previous two (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, …) shows up throughout nature. And now mathematicians have found that it also provides an answer to a variation of a classic quandary called the pick-up sticks problem: If you have a number of sticks with random lengths between 0 and 1, what are the chances that no three of those sticks can form a triangle?

Detecting Primes

The largest known prime number, 2136,279,841 − 1, is 41,024,320 digits long, but mathematicians aren’t satisfied—they want to find even bigger primes. This year a team identified a new approach for finding undiscovered prime numbers. The strategy involves partitions, or ways numbers can add up to make other numbers.

125-Year-Old Problem Solved

In 1900 mathematician David Hilbert presented a series of major unsolved problems. One of them was the goal of determining the fewest possible mathematical assumptions behind the laws of physics. Researchers later broke up this task into subgoals, and this year mathematicians claimed to have completed one of them: they unified three physical theories to explain the motion of fluids. If the achievement is confirmed, it will be a major step toward solving Hilbert’s sixth problem.

Jen Christiansen; Source: “Animation of Dudeney’s Dissection Transforming an Equilateral Triangle to a Square,” by Mark D. Meyerson (reference)

Triangles to Squares

How many pieces must you cut a triangle into to be able to rearrange it into a square? In 1902 a newspaper reader found a way to do it with four pieces, but no one has managed to do it in fewer pieces since then. This year researchers finally proved that a triangle cut into fewer than four pieces cannot be turned into a square.

Amanda Montañez; Source: “On Moving a Sofa Around a Corner,” by Joseph L. Gerver, in Geometriae Dedicata, Vol. 42, No. 3; June 1992 (reference)

Moving Sofas

Anyone who’s moved houses can appreciate the dilemma of trying to fit a large couch around a corner. Mathematicians formally recognized the question around 60 years ago when they dubbed it the “moving sofa problem”: What is the largest shape that can turn a right angle in a narrow corridor without getting stuck? Researchers have now found a solution.

Catching Prime Numbers

Another breakthrough on the prime front is a new method for estimating how many prime numbers exist within any given range of numbers. The strategy first relies on eliminating all numbers that are multiples of other primes and therefore can’t be primes themselves. It then accounts for numbers that get crossed off the list more than once. The study’s authors also discovered a limit to how precise any estimate of this sort can be, showing that the fundamental mysteries of primes will remain elusive, at least for now.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.