‘This has re-written our understanding of Roman concrete manufacture’: Abandoned Pompeii worksite reveal how self-healing concrete was made

Roman concrete is a pretty amazing material. This is one of the main reasons we know so much about Roman architecture today. Many structures built by the Romans still survive, in one form or another, thanks to their ingenious concrete and construction techniques.

However, there is still a lot we don’t understand about exactly how the Romans made such strong concrete or constructed all those impressive buildings, houses, bathhouses, bridges, and roads.

Now a new study — led by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and published in the journal Nature Communications — sheds new light on concrete and Roman construction techniques.

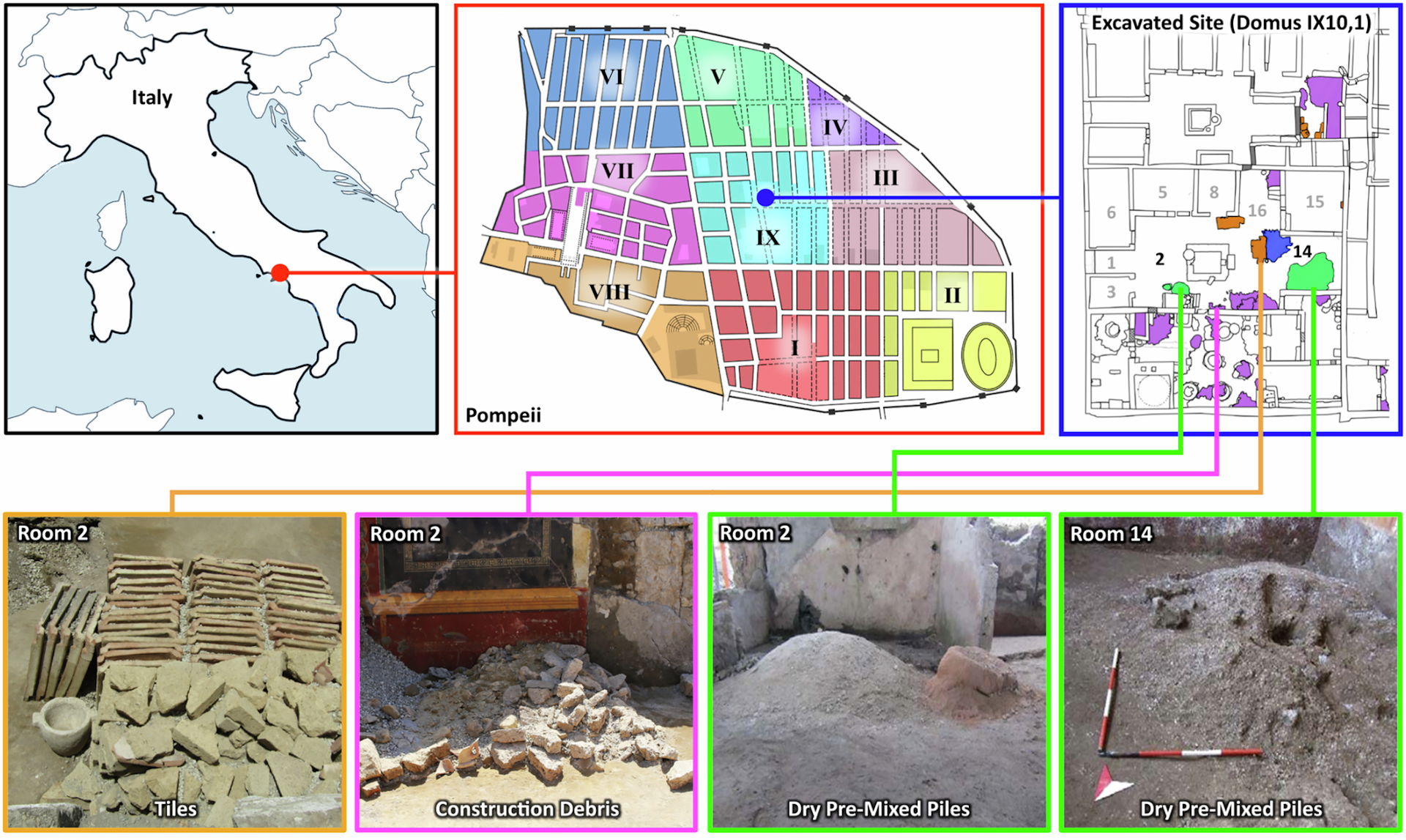

That’s thanks to details recovered from rooms partially constructed at Pompeii – a construction site abandoned by workers during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

New clues about concrete manufacturing

The discovery of this particular construction site made the news early last year.

Builders were literally repairing a house in the middle of town when Mount Vesuvius exploded in the first century CE.

This unique find included tiles sorted for recycling and wine containers called amphorae that had been reused for transporting building materials.

But more importantly, it also included evidence of the preparation of dry materials before mixing to produce concrete.

It is this dry material that is the subject of the new study. Having access to actual materials prior to mixing presents a unique opportunity to understand the concrete manufacturing process and how these materials react when water is added.

This rewrote our understanding of Roman concrete making.

Self-healing concrete

The researchers behind the new paper studied the chemical composition of the materials found at the site and defined some key elements: incredibly tiny pieces of quicklime that are changing our understanding of how concrete is made.

Quicklime is calcium oxide, created by heating high purity limestone (calcium carbonate).

The concrete mixing process, the authors of this study explain, took place in the atrium of this house. Workers mixed dry lime (crushed lime) with pozzolan (volcanic ash).

When water was added, the chemical reaction produced heat. In other words, it was a exothermic reaction. This is known as “hot mixing” and results in a very different type of concrete than what you get at a hardware store.

Adding water to quicklime forms what is called slaked lime and generates heat. In the slaked lime, researchers identified tiny, undissolved “lime clasts” that retained the reactive properties of quicklime. If this concrete forms cracks, the lime clasts react with water to heal the crack.

In other words, this form of Roman concrete can literally heal oneself.

Old and new techniques

However, it is difficult to say how widespread this method was in ancient Rome.

Much of our understanding of Roman concrete is based on the writings of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius.

He advised to use pozzolan mixed with limebut it had been assumed that this text did not refer to hot mixing.

Yet if we look to another Roman author, Pliny the Elder, we find a clear account of the reaction of quicklime with water which is the basis of exothermic reaction involved in hot mixing of concrete.

The ancients therefore knew about hot mixing, but we know less about the extent of this technique.

The most important is perhaps the detail of the texts on the experimentation of different mixtures of sand, pozzolan and limewhich gave rise to the mixture used by the builders of Pompeii.

The MIT research team had lime clasts already found (those tiny little pieces of quicklime) in the Roman remains of Privernum, about 43 kilometers north of Pompeii.

It should also be noted the healing of cracks was observed in the concrete of the tomb of the noblewoman Caecilia Metella outside Rome, on the Via Appia (a famous Roman road).

Now this new Pompeii study established that hot mixing occurred and how it helped improve Roman concrete, researchers can look for cases in which cracks in concrete were healed in this way.

Questions remain

Overall, this new study is exciting – but we must resist the assumption that all Roman construction was carried out to a high standard.

The ancient Romans could make exceptional concrete mortars but as Pliny the Elder noted, bad mortar was the cause of the collapse of the buildings of Rome. So just because they could make good mortar doesn’t mean they always did.

Of course, questions remain.

Can we generalize from the single example in this new study from 79 CE in Pompeii to interpret all forms of Roman concrete?

Does he show a progression from Vitruvius, who wrote some time earlier?

Was the use of quicklime to make stronger concrete in this house in Pompeii from 79 CE a reaction to the presence of earthquakes in the area and a prediction of cracking in the future?

To answer any of these questions, further research is needed to see how prevalent lime clasts are in Roman concrete more generally and to identify locations where Roman concrete has healed.

This edited article is republished from The conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.