Tom Wolfe’s Sociology of the Weird

Halfway into their famous 1964 road trip from La Honda, California, to New York City, Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters pulled up to a beach on Lake Pontchartrain and dropped acid. For the intrepid travelers, worn out by the July heat after days on the road in their exuberantly decorated International Harvester school bus, which wasn’t air-conditioned, the tepid Louisiana lake water was a welcome relief.

The other beachgoers did not take kindly to the white visitors’ incursion. The Pranksters, in their altered state, were slow to pick up on the situation—that they might be out of place at one of the Jim Crow South’s segregated beaches—but they were keen enough to sense the bad energy. Finally, when the cops showed up just as the whole thing threatened to turn violent, the Pranksters, rattled, were sent on their way.

Tom Wolfe raised an eyebrow as he reconstructed this scene, based on extensive interviews with Kesey and the Pranksters, in his 1969 portrait of the group, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Both Wolfe the cynical social observer and Wolfe the Southerner peek through in his description of a stop-off gone awry: Look at these naïve, white, middle-class Californians, imagining that the whole country was nothing more than their canvas. Out there on the West Coast, they had forgotten that they were white as well as middle-class, and that these things mattered in America, whether you were high or sober.

Before his encounter with the Pranksters, Wolfe had already employed his sharp pen in crafting send-ups of the New York art world, Lower East Side trust-fund bohemians, and The New Yorker. Immediately afterward, he would turn to lambasting “radical chic,” his term for high-class faux sympathy for the subaltern. You might assume, then, that the whole of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test would be a straightforward and thorough skewering of the latest bohemian craze, the Bay Area psychedelic scene, in which the Pranksters were a leading force. But it isn’t—instead, it’s a remarkably generous portrait of Kesey and his coterie that takes seriously Kesey’s conviction that their collective activities were at least as serious an aesthetic project as his novels. To Wolfe, Kesey represented an important advance in American culture, but one that also safeguarded what Wolfe thought should be safeguarded. Kesey was a divine fool, an unwitting figure in a conservative revolution.

Forgotten amid the book’s canonization as a classic work on the counterculture is just how strange it is compared with the rest of Wolfe’s oeuvre. His most formally inventive book also features his most unusual subject. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test—now republished 56 years after its release—is Wolfe’s greatest contribution to New Journalism, a term he himself coined in a 1973 anthology. This was supposed to be more than just an exciting journalistic technique: It was supposed to roll reportage, literature, and sociology into a unified whole.

The book is often praised for its efforts to replicate the experience of being on acid, to match its style to the spirit of the age. But Wolfe sought to comprehend the counterculture at least as much on his own dispassionate sociological terms as on those of its participants. He sets out to vindicate the part of it that he thought was salutary, and suitably nationalistic. That there could be something conservative in a movement built around psychedelics might have seemed odd to many readers in 1969, but it seems much less so today—a fact that would likely dismay Kesey more than it would Wolfe.

Most of Wolfe’s work—both before and after The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test—can be slotted into one of two mutually reinforcing genres. On the one hand, Wolfe threw brickbats at the world of high culture, its institutions and fads. On the other, he vindicated all that was all-American, lower-middle-class, and, in the minds of elite liberals, tacky, disrespectable, or politically suspect: Southern race car drivers, for example, or the architecture of Las Vegas. By the mid-1960s, he was known as an expert in the art of uncovering all that was new in American popular culture, in order to pass judgment on the out-of-touch Eastern establishment from which he himself operated.

But by 1966, when he began gathering material for Electric Kool-Aid, LSD was already a known quantity and had been amply covered in national and local periodicals and publications (many of them coming out of New York). The acid scene was redolent of bohemianism, something Wolfe often seemed to see as motivated by an artificial nostalgie de la boue. It had all been done before—drug-fueled road trips, middle-class kids living all piled together, rejecting the middle-class way of life as inauthentic.

Yet there was something not only novel about the acidheads but also, it seemed to Wolfe, authentically American, and in this sense unappreciated by his colleagues in the New York media. He was entranced by Kesey’s 1966 letters, penned as a fugitive in Mexico, on the run after a second arrest on charges of marijuana possession. Wolfe deemed the letters to be works of “marvelous, paranoid” prose that made him consider the Oregon-born novelist turned messianic acid-cult leader a literary peer, unlike his other subjects. Kesey was precisely the kind of guy to whom Wolfe might give the Tom Wolfe seal of approval.

Ken Kesey, after all, was the all-American kid: a star college wrestler from a small city in Oregon. His father ran a Willamette Valley dairy empire; but Kesey, having grown up in what was then still a rural part of the country, distant from its cultural centers, maintained an agrarian affectation that Wolfe admired. More simply, Wolfe liked hicks, and Kesey was one. He was the “man in both worlds,” as Wolfe put it—the intellectual one and the popular one.

On the merits of his 1962 One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Kesey had been anointed the next big thing in American fiction. The book, soon a touchstone for a burgeoning anti-psychiatry movement, follows a charismatic ruffian who organizes a revolt by the inmates of a mental institution against its staff. After finishing (helped along by acid and mescaline) his second novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, about a family of loggers who mount a quixotic battle against a union strike, Kesey seemed to decide it was time that he became the protagonist of such a drama of resistance in real life.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In 1963, after a cluster of cottages where Kesey lived just off Stanford University’s campus was demolished, he brought the remnants of his Northern California bohemian milieu, including Neal Cassady (who figured as the manic hero in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road), along with some oddball Stanford grad students and several of his old friends from Oregon, to live together on a compound he bought in La Honda, in the mountains above Palo Alto. There, where Kesey’s group began calling themselves the Merry Pranksters, things started to get weird—to depart from the by-then-familiar conventions of 1950s bohemia.

Acid helped pave the way. Kesey had been introduced to the drug through secret clinical trials arranged under the CIA’s MK-Ultra program at a veterans’ hospital in Menlo, and it took on a more central role in La Honda, where he was at work on Sometimes a Great Notion. He discovered that acid had its own agenda, one that lent itself not to hanging out all night in jazz bars, as Kerouac did, but to the construction of a distinct set of rites that would suit its intense auditory distortions and day-long mental effects. For this task, the Pranksters’ West Coast environs would prove crucial.

The 1964 road trip, whose putative purpose was to attend the launch of Sometimes a Great Notion in New York, was imagined by the Pranksters as an attempt to unleash their expanded consciousness on an unsuspecting America—and to link up with that other cell dedicated to psychedelic drugs, Timothy Leary’s commune in Millbrook, New York. It was also the stage for a movie that Kesey wanted to make, a sort of documentary of the journey he commissioned and funded, and that by this point he cared about far more than his forthcoming novel.

On the Pranksters’ return to La Honda, disappointed with Leary’s commune and with most of the vast quantity of footage shot, which had proved to be unusable (shot by amateurs in altered states), they sought other ways to make their own experiences with LSD more broadly accessible. One solution took the form of “Acid Tests,” underground parties held across the San Francisco Bay Area, for which was devised an elaborate and original audiovisual setup. The South Bay in the ’60s, dominated by the aerospace industry and full of war veterans with experience in operating machinery, was replete with engineers and tinkerers of all sorts, and the Pranksters became adept in the management of sound and light equipment. Strobe lights flashed, and the Prankster band played odd, atonal music while participants consumed acid or whatever else they wanted. The Grateful Dead played early shows at a number of these gatherings. “Curiously,” Wolfe writes, “after the first rush at the acid test, there would be long intervals of the most exquisite boredom.… The Dead might play one number for five minutes or thirty minutes. Who kept time?”

The Pranksters also developed an extensive vocabulary of their own, lovingly documented by Wolfe. To live “out front” was to live honestly and frankly, without illusions or deceptions, the way the Pranksters sought to do. To be “into the pudding” was to be well versed in the metaphysical insights that came from the psychedelic experience, among other sources (at one point Kesey realizes, to his surprise, that Nietzsche was deeply “into the pudding”). Someone’s “movie” was their worldview or way of doing things. Wolfe explains: “Everybody, everybody everywhere, has his own movie going, his own scenario, and everybody is acting his movie out like mad, only most people don’t know that is what they’re trapped by, their little script.” The Pranksters’ goal was to draw all of America into their movie.

The broad contours of Wolfe’s brand of sociology are evident in his description of the Pranksters’ deflating trip to visit Leary. When the group roars in aboard their school bus, Leary won’t come down from his study to see them. They retaliate by making fun of the crypt-like atmosphere of his compound and the self-seriousness at Millbrook. It’s clear to Wolfe that these two tribes of the psychedelic movement are symbols for broader trends in American life, split between the West (American, oppositional, authentic) and the East (Europeanized, derivative, inherently institutional). Leary stands for “straw rugs and Paisley wall hangings,” Kesey for “neon, Buick Electras, mad moonstone-faced Servicenters.” Like Wolfe himself, Kesey was an intellectual against the intellectuals.

Likewise, Wolfe emphasizes the Pranksters’ difference from what we think of as the hippie aesthetic—paisley and tie-dye, all manner of appropriation (harem pants, Native American headdresses). The Pranksters’ uniform was jeans and cowboy boots spray-painted with Day-Glo, a freaked-out twist on Americana.

Kesey thus emerges in Wolfe’s portrayal as a kind of nationalist figure at the heart of an anti-nationalist moment—something that shows up in Kesey’s politics, too. Wolfe doesn’t disguise his glee in describing Kesey’s speech at an anti-war march in Berkeley in the fall of 1965, in which he accused another speaker of resembling Mussolini and said, “You’re not gonna stop this war with this rally,” and added that by marching, “You’re playing…their game.” If psychedelic adventurism could be made to serve political quietism, Wolfe wasn’t opposed.

But he was convinced that the Pranksters represented more than just a patriotic counterweight to a more general liberal anti-Americanism. For Wolfe as for Kesey, the Pranksters formed a bridge between the Beat movement of the ’50s and what became known as the counterculture of the ’60s—symbolized by Haight-Ashbury, the “Human Be-In” in Golden Gate Park, and all things long-haired and flower-adorned. The Pranksters, Wolfe argues, reconciled the icons of the previous decade (Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady) with figures whose stature would grow in the years to come (Jerry Garcia and Mountain Girl). But in making this connection, the Pranksters also threw a dose of conventionality into the midst of a cultural revolt.

Wolfe was taken by the idea that the Pranksters represented the drawing together of two decades of American cultural insurgency into a synthesis that was surprisingly compatible with Middle American sensibilities. What would come in the decades after the Pranksters—from acid rock to the Whole Earth Catalog to Burning Man and Silicon Valley’s early pirate stylings—can be traced, in considerable measure, to Kesey and the scene in which he was a protagonist. Today, many people live the life of Paul Foster, one of the figures in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, who alternated between working lucrative jobs as a computer programmer and spending months at a time doing drugs and living the Prankster life. Over the decades since the 1960s, America assimilated the counterculture; in Kesey’s scene, it came pre-assimilated.

The old bohemianism, the Beats included, was premised on small groups of people willing to sacrifice middle-class respectability to live against society and produce art. Kesey started off this way, but jettisoned literature in favor of aestheticizing the Prankster way. The byproduct of his labors was aiding in the transformation of bohemianism into a mass cultural product—the alternative lifestyle.

Honesty and immediacy were prized values among the Pranksters, and all philosophical and cultural references were deemphasized. When Norman Hartweg, a writer for an LA alt-weekly, came up to see what the Pranksters were about, he found that they were interested in none of the “common intellectual currency” of the LA hip scene—books, movies, political movements, and so on: “They don’t even use the usual intellectual words here—mostly it is just thing.” Drugs provided the common currency of intellectual activity among the Pranksters, and anyone could take them. Hartweg was fascinated. Struggling to write the piece he had come to report, which now seemed less important, he began seeking acceptance into the Prankster group itself.

This anti-allusive tendency helped make the Pranksters’ sensibility widely appealing: Kesey was able to rope in the infamous Hells Angels biker gang to become part of his broader crew, a feat of engagement with “real life” that few other intellectuals could claim. It explains something of the way that elements of the Prankster ethos could find a mass audience through the spread of the psychedelic style. Ultimately, the Pranksters criticized Hartweg for being “lazy and not contributing.” His habits of reading and cigarette-smoking, they reasoned, were selfish activities that carried no benefit for the others in the group.

In that regard, and perhaps in others, the Pranksters did not entirely float free of the prejudices of their own middle-class backgrounds. Wolfe says they unwittingly replicated those social dynamics: Good looks and athletic ability were rewarded among them no less than at the prototypical American high school. Even more evident was what the Pranksters ignored: Black figures and culture had been of great importance to the Beat movement, but there would be little place for either in the new psychedelic scene.

Kesey’s group (and the broader Bay Area cultural scene) instead venerated the Hell’s Angels, who were perhaps not, in the final estimation, infinitely more than middle-class white Californian guys who liked drinking and motorcycles and bar fights more than the average. Wolfe speculates that the acid scene seemed to appeal most to kids from the suburbs who didn’t quite fit in there, that it was a world familiar to them in its social contours, if more accepting of certain kinds of oddballs.

Wolfe was writing at a time when the middle class had conquered almost everything in America; he wrote about this explicitly in his early journalism. The Baby Boom and postwar prosperity had created an exceptionally comfortable and numerous generation of young people now busy toppling the old tastemakers and gatekeepers. The left believed this generation would lead them to victory. Wolfe believed that they would instead conquer the final keep—cultural revolt—and claim it, too, for the mass middle-class sensibility. He was right.

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test is Wolfe’s formal triumph, the most fully formed exercise in the style he developed beginning in 1963. Just as he was fascinated by things that seemed to make modernism into something crowd-pleasing and vernacular, his prose was an effort in the same direction, an attempt to get readers of mainstream American magazines to read essays and books that displayed some of the flavor of modernist prose but was easier to digest. In Electric Kool-Aid, Wolfe modulates in and out of the Pranksters’ own unique vocabulary and style; clusters of punctuation marks, small caps, and extended onomatopoeia litter the pages, interspersed with verses of 1960s doggerel, all serving to capture the mania and paranoia of his subject, and of the time.

Kesey and his scene aroused both approbation and condescension in Wolfe. This made Electric Kool-Aid his most ambivalent portrait, and his finest. But he didn’t continue writing this way: 1979’s The Right Stuff was more stylistically restrained and a tonal retreat into familiar territory: the righteous good old boys oppressed by bean-counting bureaucrats. And Wolfe’s novels, though sociologically rich, feature mostly stock characters, with none as finely textured as the individuals who populate The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Tracking Kesey’s tragicomic rise and fall as a Bay Area cultural figure, Electric Kool-Aid resembles in outline the plots of Wolfe’s first two novels, The Bonfire of the Vanities and A Man in Full. In it, a heroic redneck struggles against the forces of order, elevating his ragtag band to a higher level of consciousness and arousing a furious response from without. The hero is defeated in the end, but hope springs eternal. Wolfe’s Kesey, then, wins us over with his charisma, despite how ridiculous he often seems.

In Wolfe’s story, the betrayal was that of the broader countercultural scene in the Bay Area, which closed ranks against Kesey when he insisted on the necessity of leaving LSD behind and continuing the expansion of consciousness by new means, carrying the insights provided by LSD into daily life in a way that did not depend on repeated consumption of the drug. His 1966 “Acid Test Graduation” was granted a massive venue at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom by counterculture impresario Bill Graham, only for Graham to cancel at the last minute, having been prevailed upon by angry hippies who suspected that Kesey—out on bail after his return from Mexico—was trying to undermine the psychedelic movement to curry favor with the feds, perhaps as part of some secret deal. There’s no reason to think Kesey had such motivations—although, facing a long prison term if he were to violate the terms of his bail, he had no desire to engage in further provocation of the forces of order, not wanting to meet a fate like that of the lobotomized Randle McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

But whereas Cuckoo’s Nest ends in genuine tragedy, Electric Kool-Aid closes with a bathetic anticlimax: Kesey and the remnants of the Pranksters sitting around yelling, “We blew it!”

It’s tempting to take that phrase as an epitaph for the ’60s. But Kesey never seemed to consider, either in his novels or in his cultural activities, that there was another possibility for messianic movements besides victory or the kind of defeat in which one could dream of later victory.

Today, Kesey’s vision seems more expedient than messianic. Like many of his generation, he imagined the apparatus of the mid-century state to be all-powerful, almost totalitarian, personified by the inhuman Nurse Ratched of Cuckoo’s Nest. In the end, that world was a fragile one. Shuttering the mental institutions and smashing the unions turned out to be surprisingly easy and, for the ramparts behind which real power lay, convenient indeed. Kesey was wrong when he told the crowd at Berkeley that they wouldn’t end the Vietnam War by marching. But it turned out that the American empire was able to adapt to the cries of protest without too much trouble.

Was it Kesey himself who had unwittingly been “playing their game” after all, a flash of acid paranoia come true? From today’s vantage, his legacy has begun to take on the opposite shape of the story that he, and Wolfe, wanted to tell: one not of victory in defeat, but of defeat in victory.

More from The Nation

The legendary jazz drummer played with Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis, and Stan Getz. His new memoir tells all—and lays out his own philosophy.

Billy Hart

The Yiddish writer’s lost masterpiece, Sons and Daughters, brought back to life, in all its humor and beauty, the Jewish shtetl of his youth.

Lily Meyer

A new play about Roald Dahl shows the now-controversial children’s writer in his flawed, complicated reality.

Katha Pollitt

Nathan Kernan’s biography of the New York School poet tracks the development of his serene and joyful work alongside the chaos of his life.

Books & the Arts

/

Evan Kindley

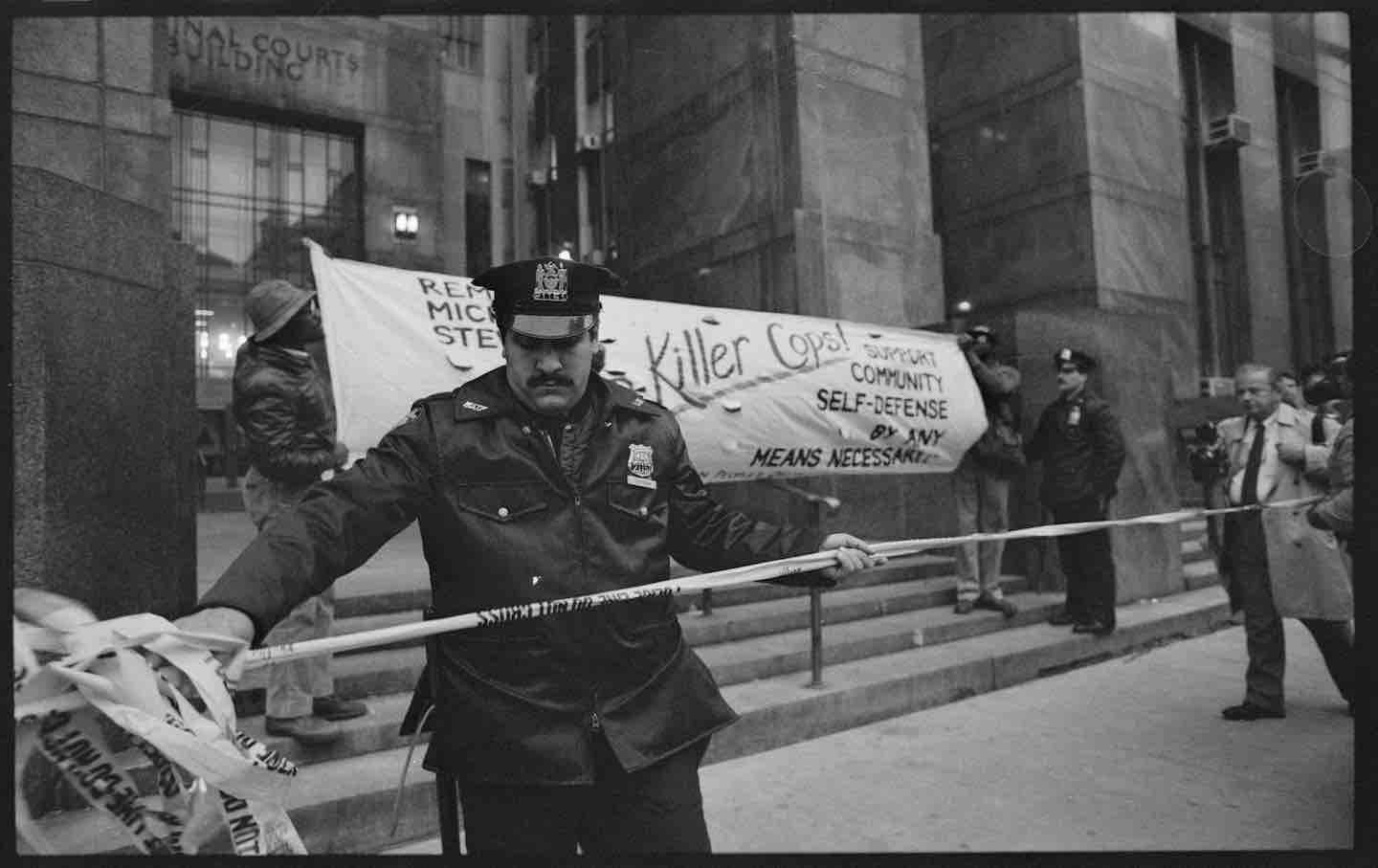

In 1985, police were acquitted in the killing of a graffiti artist and painter, a grisly act that galvanized the city’s art underground. Why has he been forgotten?

Books & the Arts

/

Michael Shorris

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/potato-leek-tart-GettyImages-1291502014-a580b91374ac499d8dbfc3a7da99c648.jpg?w=390&resize=390,220&ssl=1)