Science history: Scientists use ‘click chemistry’ to watch molecules in living organisms — Oct. 23, 2007

QUICK FACTS

Milestone: Scientists develop chemical recipe to observe molecules of living creatures

Date: October 23, 2007

Or: The University of California, Berkeley and other laboratories

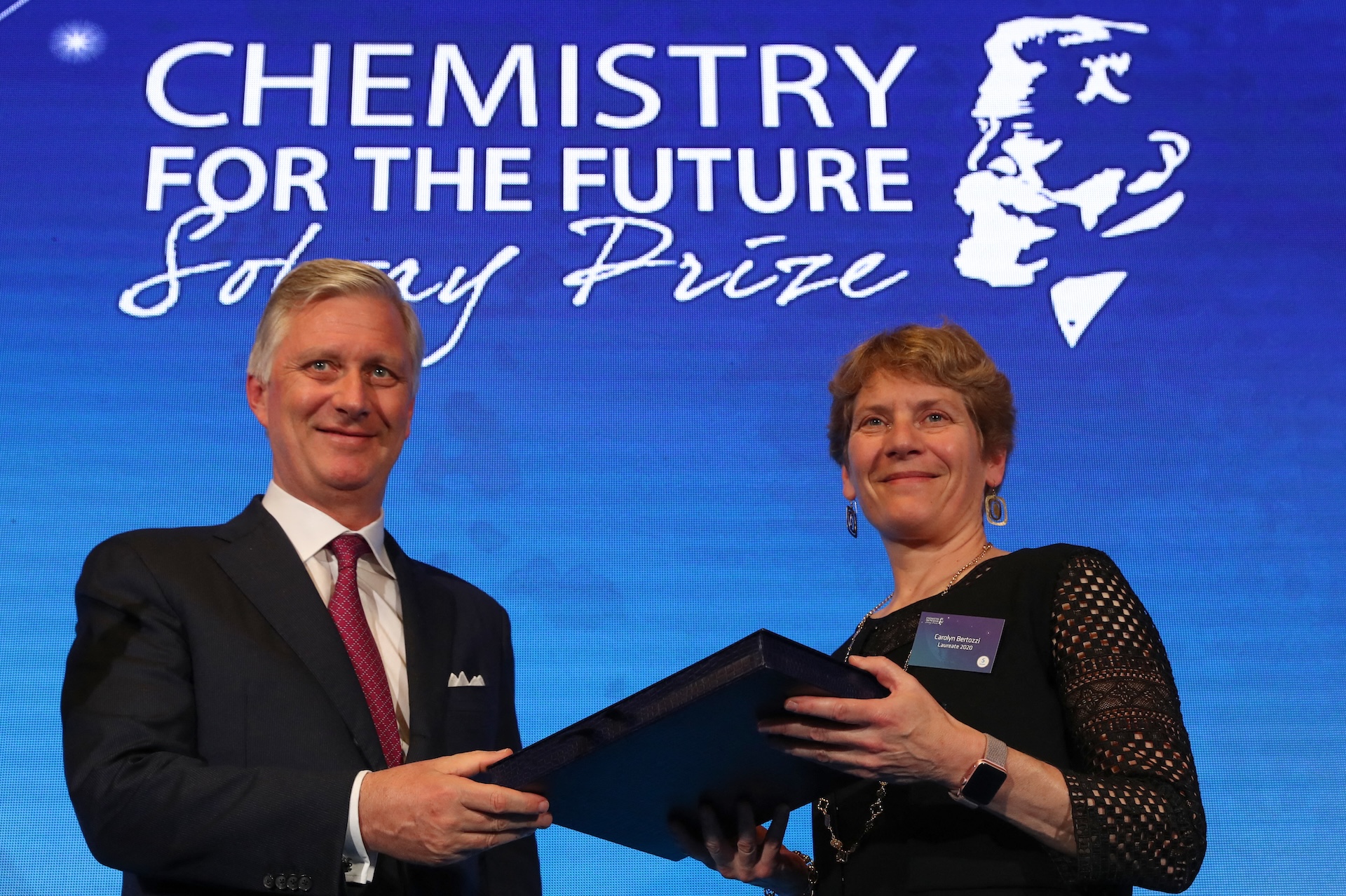

WHO: A team of scientists led by Carolyn Bertozzi

In 2007, scientists published a paper who established a recipe for a new type of biochemistry. The method would allow scientists to see what is happening in organisms in real time.

Glycans are one of the three major classes of biomolecules (along with proteins and nucleic acids) and have been involved in inflammation and diseasebut scientists found it difficult to visualize them. To do this, Bertozzi relied on a chemical approach developed by biochemists K. Barry Sharpless, of Scripps Research, and Morten Meldal, of the University of Copenhagen.

Sharpless had presented a vision for “click chemistry”” – a way to quickly build complex biological molecules by assembling smaller subunits.

Biological molecules often have linked backbones carbon atoms, but carbon atoms do not want to bond. This meant that historically, chemists had to use careful, multi-step processes that used multiple enzymes and left unwanted byproducts. This was good for a laboratory but bad for the mass production of biomolecules for pharmaceutical products.

Sharpless realized that they could simplify and expand the process if they could assemble simple molecules that already had a complete carbon structure. They just needed a connector that was fast, powerful and reliable.

Separately, Sharpless and Meldal stumbled upon the critical connector: a chemical reaction between the compounds azide and alkyne. The trick was to add copper as a catalyst.

THE reaction was extremely powerful and fast, and more than 99.9% time, without producing by-products.

But for Bertozzi, there was a problem: copper is very toxic to cells.

Bertozzi therefore scoured the literature to design a click chemistry that was safe for living cells. She found the answer in decades-old work: azide and alkyne would react “explosively,” without the need for a catalyst, if the alkyne was forced into a ring shape.

In 2004, his team demonstrated that this reaction could be used to attach azide molecules to living cells without harming them. And in 2007, Bertozzi and colleagues used his method to visualize glycans in living hamster cells.

His process involved incorporating a carbohydrate molecule modified with azide into the glycans of living cells. When they added a ring-shaped alkyne molecule linked to a green fluorescent protein, the azide and alkyne clicked together and the bright green protein revealed the location of the glycans in the cell.

Bertozzi dubbed the process “bioorthogonal click chemistry” – so named because it would be orthogonal to – that is, would not interfere with – the biological processes occurring in the cell. His work has proven crucial to understanding how small molecules move within living cells. It was used to track glycans in zebrafish embryos, to see how cancer cells protect themselves from immune attacks using sugar moleculesand develop radioactive “tracers” to biomedical imaging. And more broadly, click chemistry has boosted the process of drug discovery.

In 2022, Sharpless, Meldal and Bertozzi won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on click chemistry.