Why redistricting is so important, in 3 charts

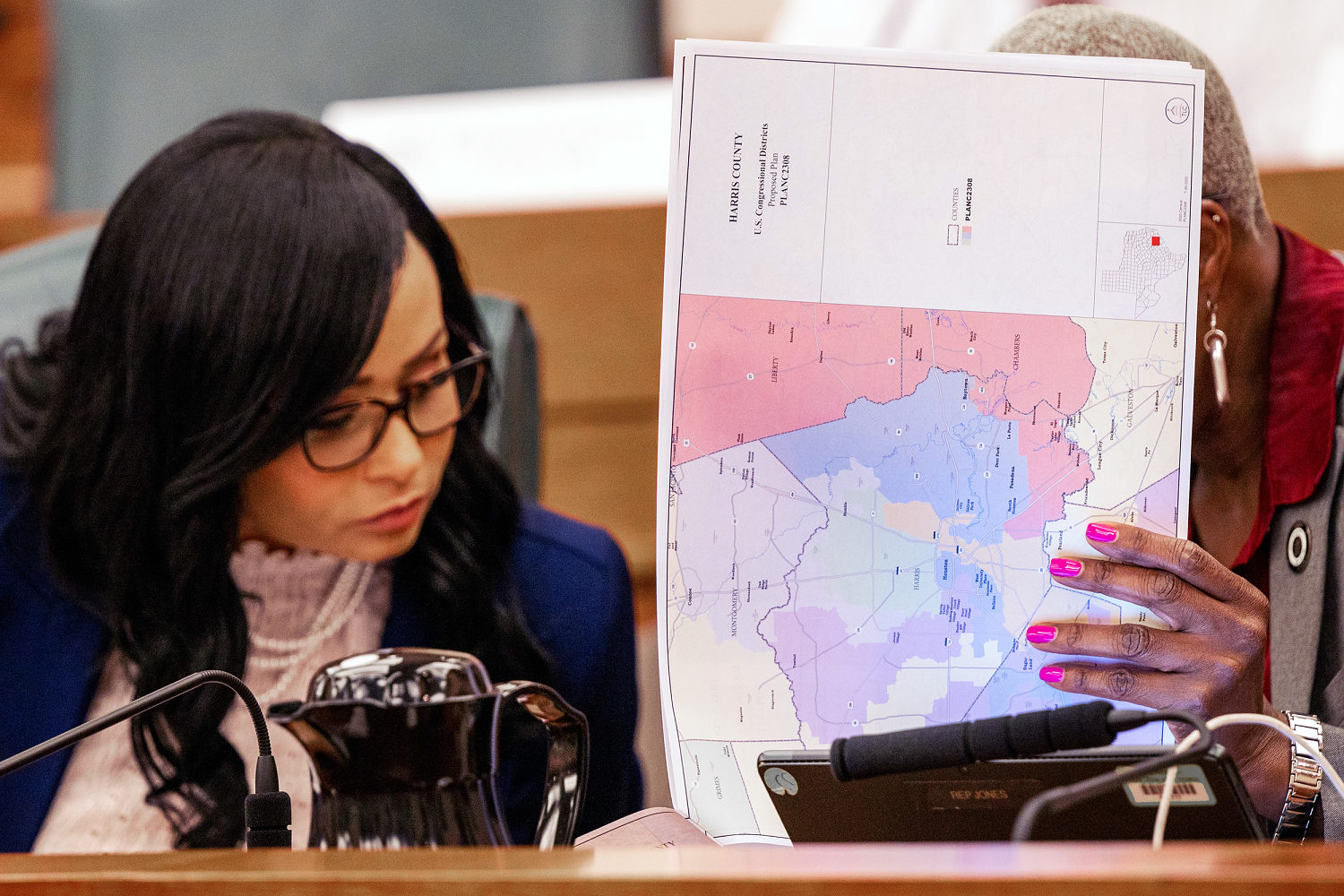

The move of Texas Republicans to redesign their congress card in the middle of the decades and the efforts to rediscover the Democrats attracted national attention to a very simple reason: how the districts of the house are drawn can shape American politics for years.

Gerrymandering generally reduces the number of competitive breeds, and it can lock almost motionless advantages for one or another. As part of the new card offered in Texas, no presidential vote of the absence of a seat would have been decided by a single figure in 2024, and the Republicans would have a path to repel their close majority of the congress during the mid-term elections of 2026. This means that more people could reside in the districts of the congress under the solid control of a party.

NBC News analyzed how the question of which draws the cards – and how they do it – can shape the elections for years after.

The difference between safe seats and competitive districts

Who traces district lines can differentiate between the general elections contested in a state in November and the elections which are barely more than formalities.

NBC News analyzed each house race in the country from 2012 to 2020, the last 10 -year -old complete redistribution cycle, on the basis of how each district has been drawn. In the states where the legislators of the States have drawn the cards, the races to a figure (elections in which the winners won by less than 10 percentage points) were the rarest. Only 10.7% of house races fell into this competitive category.

There are many reasons that do not involve gerrymandering. On the one hand, the voters of the two parties have become more and more gathered in recent years, leaving fewer places across the country which are politically divided.

However, Gerrymandering plays an important role. When the state or federal commissions or courts have drawn the lines of the last decade, the rate of competitive elections jumped, although the safe seats are still extremely likely. Competitive elections were particularly widespread in states with court districts: 18.1% of the races in these states had margins with a figure from 2012 to 2020.

An overview of the Pennsylvania, whose card drawn by the legislature was thrown and replaced in 2018 by the Supreme Court of the State, illustrates the dramatic change which can occur on which traces of the lines of the Congress. The same state with the same voters living in the same places suddenly had many more competitive elections.

From 2012 to 2016, only three of the 54 general elections of the Pennsylvania house as part of the initial map had margins to a figure.

After the Supreme Court of the State threw the map and imposed a new one, the number of battlefield races increased. Eight of the 36 house races had a figure margins in 2018 and 2020.

Meanwhile, before mid-term of 2026, the Cook political report with Amy Walter assesses 40 home districts like launchers or slightly leaning towards a game. More than half (23) of these 40 competitive districts are in states where commissions or courts have attracted cards.

How the partisanry of a state compared to whom he sends to the Congress

The power of the redistribution process can bend the representation of a state at the congress far from its global partisanary, with large differences between the state -scale vote in certain states and the composition of their delegations to the Chamber.

Take the Illinois, for example, where Donald Trump obtained 44% of the votes in 2024. The Republicans only hold three of the 17 seats of the State in Congress, or 18%. (NBC News examines the presidential data instead of room data here because certain breeds are undisputed.) And even if Trump obtained 38% of the votes in California last year, the Republicans hold only 17% – or nine seats – of the 52 districts of the Congress of the State.

On the other side of the big book, Trump obtained a 58% support in South Carolina last year, and 86% of the delegation of the State Chamber is a republican. In North Carolina, 51% voted for Trump last year and the Republicans have 71% of the delegation.

The comparison between the house seats and the performance of the presidential elections is not perfect. But that shows that the way the district lines are traced can generate different results from what state results can suggest.

In the middle of the graphic is Virginie. Its 11 Congress districts divided 6-5 for Democrats, which means that the Republicans hold almost 46% of state seats in Congress, and Trump won 46% of votes in Virginia last year.

In addition, it is not because the cards of a state promote a part compared to the results on the scale of the state after an election does not mean that the redistribution process has been biased. According to the report, according to the Political Political Political Report report or Lean-Up-up or Republican in 2026.

Each state traces its own course

Given that each state is responsible for the management of its own redistribution, the process is different depending on where you look, giving immense power to different state institutions by State.

In 27 states, the legislatures approved the cards. In seven, the independent commissions approved them, seven had cards approved by the court, two had political commissions and the cards of a state were approved by a safeguard commission, according to data from the Loyola Law School. (The six states that elect a single person in the House do not draw new Congress cards.)

The “All about Redistrict” website of the Loyola Law School defines the commissions of politicians because elected panels can be members. The website defines backup commissions as safeguard procedures if the legislatures cannot agree on the new lines.

Certain independent redistribution commissions are not as powerful as those of other states. New York has an independent commission, but the legislative assembly exceeded its card and adopted its own in 2024.