Wireless power grids head to the moon

A future lunar lander bound for the far side of the Moon will carry with it equipment that could make these missions a little brighter.

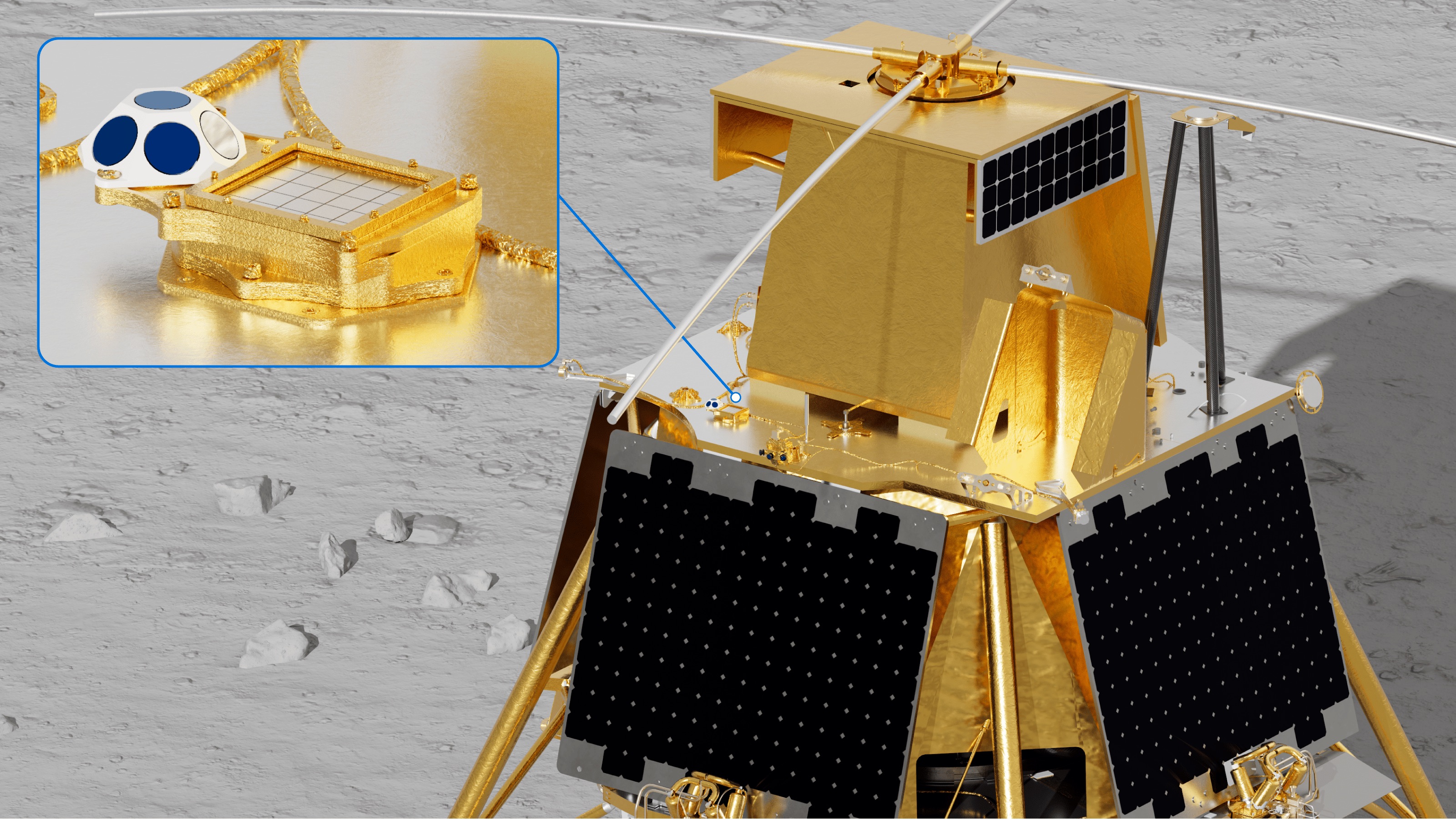

The lander in question is operated by Firefly Aerospace, the first commercial company to successfully land and operate a spacecraft on the Moon. A LightPort wireless power receiver will be mounted atop the upper deck of the Firefly Blue Ghost lander. Developed by Canadian aerospace startup Volta Space Technologies, the cargo ship plays a key role in Volta’s ultimate goal: establishing a network of satellites capable of wirelessly transmitting solar energy to spacecraft on the lunar surface. Their bet is one of several emerging efforts to maintain a functioning “power grid” on the Moon — a critical step toward conducting longer lunar expeditions and, one day, creating viable human habitats.

Volta calls its proposed wireless system LightGrid. They say this would work by integrating LightPorts (the receivers) into future rovers, landers and other lunar vehicles. These LightPorts would receive solar energy transmitted via lasers from orbiting satellites. If it works, the system could ensure a constant supply of energy, even during the long, dark lunar nights. A single evening is equivalent to approximately 14 days on Earth.

Firefly plans to launch its lander to the Moon’s South Pole by the end of 2026. Assuming it arrives in one piece, the receiver will attempt to capture a signal from an orbiting satellite to test and validate whether the system actually works as intended.

“This collaboration allows us to test our LightPort receiver in a real-world lunar environment and take a step closer to providing a fully integrated power grid for the Moon,” Justin Zipkin, CEO of Volta, said in a statement. Volta did not immediately respond to Popular science request for comment.

[Related: This giant solar power station could beam energy to lunar bases]

Bringing energy to the Moon

Developing methods to reliably maintain electrical power approximately 240,000 miles from Earth is crucial if NASA and its international compatriots are to realize their vision of longer lunar visits. Beyond just keeping the lights on, constant power is needed to heat the equipment and keep it from breaking down on cold moon nights. In constantly shaded regions, the Moon’s frigid surface can rival Pluto’s and reach temperatures of -410 degrees Fahrenheit (-246 degrees Celsius). Solar panels attached to rovers and landers can temporarily fill the gaps, but prolonged periods without sunlight render them useless.

Volta has already tested its approach in the laboratory and in the field, apparently at ranges up to 2,789 feet (850 meters). There are still many unknowns in terms of expected energy production, but a company executive recently said Space news that he believes “full service” power for a customer (most likely a rover operator) on the lunar surface would require the radiation power of three small satellites operating in low lunar orbit. Scaling LightGrid to cover a larger area or more vehicles would likely require an entire fleet of satellites adjacent to the Moon.

[Related: Six weeks, three moon landers: The era of private space exploration is here]

However, LightGrid is not the only approach being considered. Astrobotic, a Pittsburgh-based aerospace startup, has spent years developing its own lunar energy solution, called LunaGrid. In this case, the company built several solar power plants connected by transmission cables spanning several kilometers of surface area. A fleet of small mobile robots equipped with retractable solar panels would then depart from these stations to charge larger vehicles. Astrobotic compares these mini rovers to an extraterrestrial extension cord.

NASA is also showing renewed interest in installing a nuclear reactor on the Moon. The idea dates back decades, but was redefined earlier this year after acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy issued a directive urgently calling for the development of a 100-kilowatt fission reactor at the Moon’s South Pole by the end of the decade. Energy experts chatting with Wired earlier this year said the accelerated timeline was ambitious, but not necessarily out of reach. China and Russia, meanwhile, are also racing to build their own lunar nuclear reactors.

A fully functional future lunar habitat will likely require a combination of all of these approaches in order to create a reliable power grid capable of withstanding a harsh environment. By hitching a ride on Firefly’s lander, Volta gets a head start. But this advantage may not last long.

The maturation of several private aerospace companies, like Firefly, Intuitive Machines and ispace, means that landers are starting to reach the Moon at a staggering rate. NASA alone has 15 commercial lunar delivery contracts that are expected to come to fruition by 2030. These deliveries focus not only on supporting exploration and testing of power grids, but also on less obvious efforts, such as establishing lunar cell networks and spectrum deployment.

In other words, Earth’s closest extraterrestrial neighbor is about to get a lot more populated. And maybe a little brighter.