Human eggs have special protection against certain types of aging, study hints

A new study suggests that human egg cells can be protected from certain age -based changes observed in the rest of the body.

The work, published on August 6 in the review Scientific advancesdid not explore the functioning of this protection, but he highlighted a striking difference between the mitochondria – the cellular powers – found in the blood and saliva of adult women and those carried in their eggs. The mitochondria bear their own special DNA, and as the body ages, this DNA matt. But there seems to be an exception to this rule within mitochondria in human egg cells.

Mitochondrial DNA changes (MTDNA) are not always harmful, but in some cases they can cause diseases that affect the body’s ability to make and use energy. These conditions can be fatal. There is no approved remedies and treatments are generally focused on softening symptoms rather than correction of the underlying problem. As such, it is important to understand if egg mitochondria collect more mutations as they age, as this could increase the risk of such diseases in children.

This could potentially be a factor to consider in family planning. For example, if the risk of pathogenic mitochondrial mutations was extremely high in older eggs, this could be an argument to freeze his eggs at a younger age, co-author of the study Barbara ArbeithuberA research group manager at Johannes Kepler Linz University in Austria, Live Science told an email.

However, mitochondria is not the only factor to consider in the quality of eggs because we know that egg cells decrease other ways as they age. And above all, this new study “does not tell us directly on reproductive interventions, because they were not the subject of our work,” said Arbeithuber.

“It is premature to apply these results to clinical practice,” said the co-author of the study Kateryna MakovaProfessor of biology at Penn State. “Our results should be reproduced in a larger number of women and validated in other human populations,” Makova told Live Science in an email.

In relation: 8 years suffering from a rare and fatal disease shows a spectacular improvement in experimental treatment

Partially “protected” eggs of aging

Studies suggest that at older age, egg cells Collect new changes In their chromosomes, DNA found in the nucleus of cells. There is evidence that older eggs, or egg cells, are Less capable of repairing DNA damage that the youngest oocytes. In addition, the pregnancies that occur at maternal ages aged 35 and over are associated with a higher rate of chromosomal anomalies than pregnancies at younger ages. This is partly due to changes in eggs that make them more likely to have a abnormal chromosomes When they reach maturity.

(In particular, advanced paternal age also increases the rate of genetic anomalies in offspring, therefore Sperm – not just eggs – also help Mutational charge.)

But while the effect of aging on chromosomal DNA in eggs and sperm is fairly well studied, the understanding of scientists of what happens to DNA in the mitochondria of an egg as it ages is less clear.

“For human oocytes, the previous reports were controversial,” said Arbeithuber. The methods used to analyze DNA in these previous studies were not precise enough to reduce the actual rate of mitochondrial mutations. Arbeithuber and his colleagues used an approach called duplex sequencing, which has a much lower error rate.

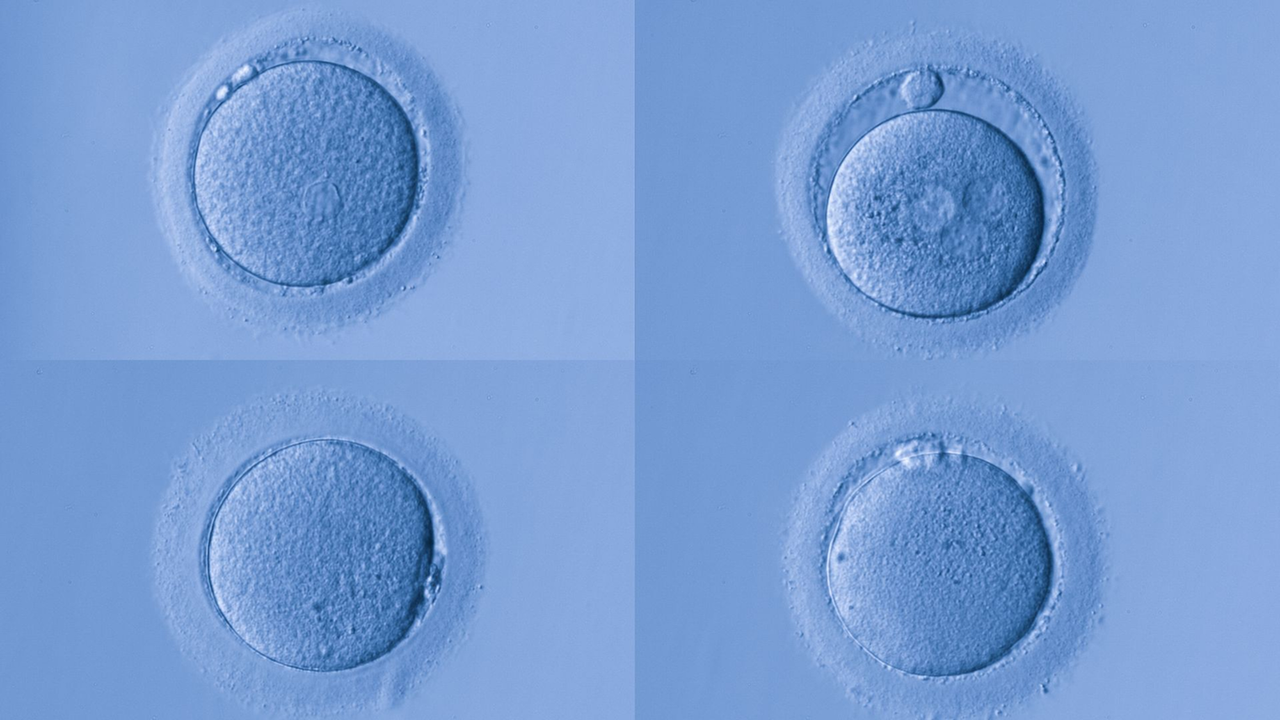

For the study, they recruited 22 women aged 20 to 42 who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF). For each participant, they analyzed blood and saliva samples, as well as a five oocytes. In total, they evaluated 80 egg cells on the 22 women.

In all the blood, spindle and egg samples, the mitochondria of eggs had 17 to 24 to 24 less changes than those of blood and saliva. And that the relatively low rate of mutations has remained stable. The number of mutations observed in the blood has increased the most in age groups, followed by saliva, and there was no statistically significant increase in the number of changes in the eggs.

When the team has zoomed in on the few mutations that appeared in the eggs, they found that they were less likely to have an impact on DNA previously linked to the diseases than the mutations observed in the blood and saliva.

“The good news is that, contrary to what is happening in other fabrics of the body such as blood or saliva … Human oocytes accumulate no more mutations as women age, at least between 20 and 42 years old,” Filippo ZambelliA principal consultant at the TRT Consultancy Reproductive Medicine Service in Barcelona, Spain, told the Science Media Center. “This suggests that DNA in oocytes is protected against aging and its potential negative impact on cellular function,” said Zambelli, who was not involved in research.

“Overall, this study is reassuring for people who try to conceive of children at subsequent ages, because, although chromosomal anomalies increase with maternal age, at least they should not expect a higher level of mutations in their DNAD,” he said. However, this study included only 22 people, so that the results are confirming in larger studies, he added.

Following steps

Before the new study, the same researchers had studied mitochondrial changes mouse And monkeys. In mice, they observed an increase in DNA mutations with age in egg cells and other body tissues, such as muscle. In monkeys, they found that mutations increased in eggs and other fabrics until primates reach approximately 9 years – equivalent to around 27 years in human years. At this stage, the rate of mutation of eggs has flatten while other parts of the body have accumulated more and more DNA changes.

“It is possible that this is also the case in humans,” suggested Arbeithuber, which means that eggs may accumulate certain mitochondrial mutations in previous life and then stop at a certain point.

Their new study was somewhat limited in that they obtained eggs from people with IVF, so “we were limited by the age of people who consult such a clinic,” she added. In the future, it could be interesting to analyze the eggs of younger age groups and through generations, from mothers to children, she said.

At this point, researchers do not know how mitochondrial DNA in eggs remains preserved over time while other tissues are ripening. “This is an open question,” said Arbeithuber. In their article, the team proposed that there can be a process that helps to eliminate harmful changes in the DNA of oocytes, but additional research will be necessary to confirm this idea.

This article is for information only and is not supposed to offer medical advice.