After Series of Denials, His Insurer Approved Doctor-Recommended Cancer Care. It Was Too Late.

For nearly three years, Eric Tennant endured chemotherapy infusions, rounds of radiation, biopsies and hospitalizations that left him weak and exhausted.

“It’s good to be home,” he said after a hospitalization in early June, “but I’m tired and ready to move on.”

In 2023, Tennant, of Bridgeport, West Virginia, was diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma, a rare cancer of the bile ducts that had spread throughout his body.

None of the initial treatments prescribed by his doctors eradicated the cancer. But a glimmer of hope appeared in early 2025, when Tennant was recommended for histotripsy, a relatively new procedure that would use ultrasound waves to target, and potentially destroy, the largest tumor in his body – that of his liver.

“My dad was a little nervous because it was something new, but it definitely gave us hope that he would be around a little longer,” said Tennant’s daughter Amiya.

There was just one problem: his insurer didn’t want to pay for it.

Tennant, 58, died of cancer on September 17. Her story illustrates how a bureaucratic process called prior authorization can devastate patients and their families.

Becky Tennant believes her husband could have lived longer if their health insurance hadn’t repeatedly denied a new treatment recommended by his doctor earlier this year. “It may not have changed the outcome,” she said, “but they took that away from us to find out.” (Rebecca Tennant)

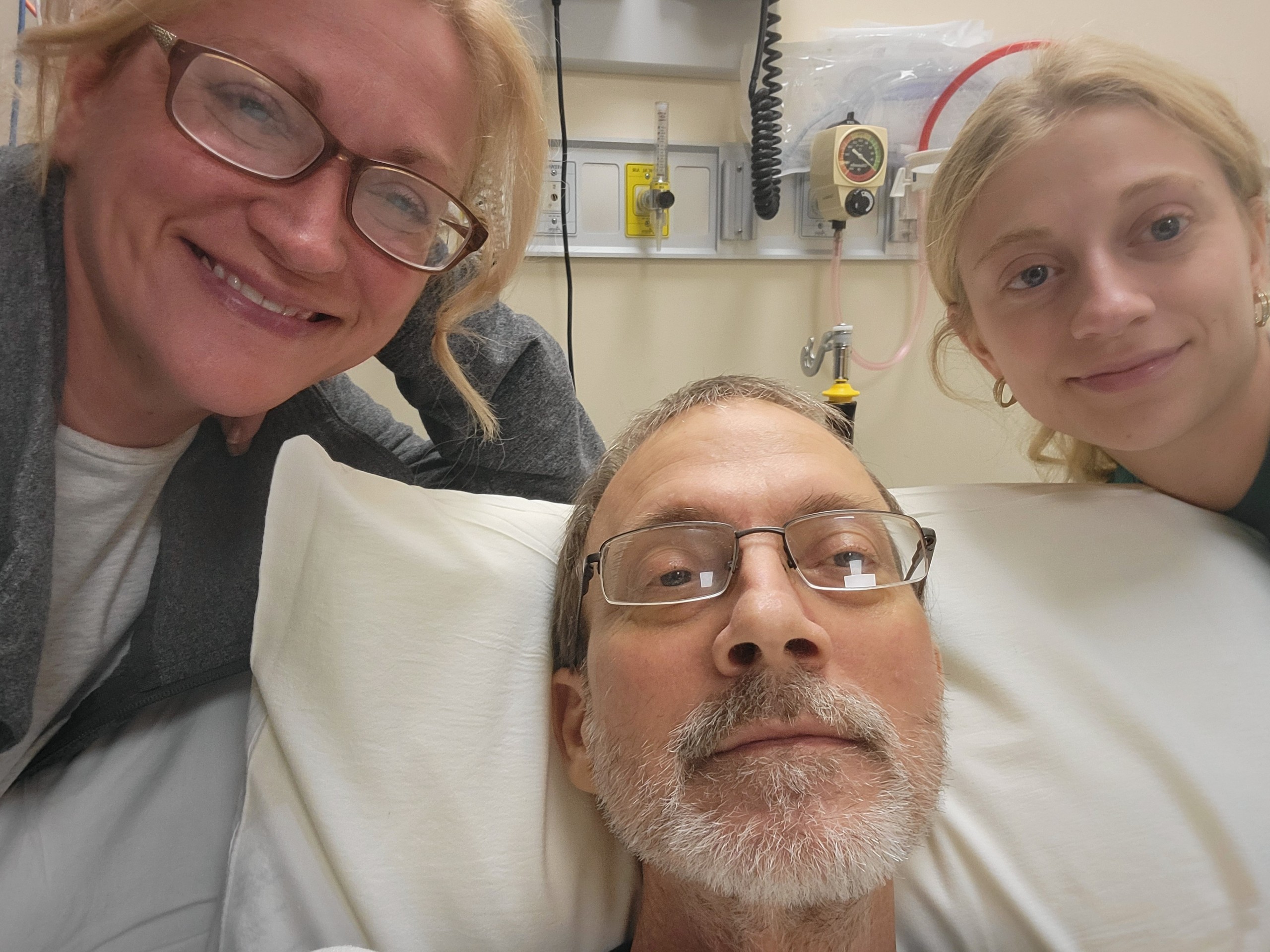

For months, Eric Tennant’s health insurance refused to cover cancer treatment recommended by his doctor, saying the procedure was “not medically necessary,” a common reason insurers use to deny care. (Part of this photo is digitally blurred to protect patient privacy.) (NBC News)

It is impossible to count the people harmed by this extremely unpopular practice which, by delaying or refusing care, contributes to increasing the profits of health insurers. No government agency or private group tracks this data.

That said, KFF Health News has heard from hundreds of patients in recent years who say they or a family member was harmed because of prior authorization. More than one in four doctors surveyed by the American Medical Association in December said a prior authorization resulted in a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. And 8% responded that prior authorization resulted in disability, birth defects or death.

In June, the Trump administration announced a pledge, signed by dozens of private insurers, to streamline prior authorization, which often requires patients or their medical teams to seek authorization from insurers before proceeding with many types of care. It is still unclear when patients can expect improvement.

The commitments “are dependent on the full cooperation of the private insurance industry” and “will take time to have their full effect,” said Andrew Nixon, a spokesman for the Department of Health and Human Services. But the commitment exists, he said, “to prevent tragic deaths like Eric’s from happening at the hands of an ineffective system.”

Chris Bond, a spokesman for AHIP, a health insurance industry trade group, said he couldn’t speak to any specific insurer’s prior authorization policies. Generally speaking, however, he said prior authorization “acts as a safeguard” to ensure that medications and treatments are not used inappropriately.

At the same time, he said, insurers recognize that patients can be frustrated when they are denied care recommended by their doctors. That’s why “the entire industry is working to make the process more direct, faster and simpler for patients and providers,” Bond said.

Meanwhile, the process continues to take its toll on people like Eric Tennant, whose serious diagnoses often require expensive health care.

“Eric is gone,” said his widow, Becky. “He won’t come back.”

Tennant was a safety instructor for the West Virginia Office of Juvenile Health, Safety and Training and insured by the state’s Public Employees Insurance Agency, which contracts with UnitedHealthcare to administer benefits for state employees, their spouses and dependents.

In February and March, UnitedHealthcare, the Public Employees Insurance Agency and an outside examiner issued a series of denials concluding that Eric’s benefits would not cover histotripsy, saying the treatment was not medically necessary. Becky Tennant estimated the procedure would cost the family about $50,000 out of pocket.

Although the treatment wasn’t guaranteed to work, the Tennants believed it was worth the effort. So they considered withdrawing money from their retirement savings. But then, in May, after KFF Health News and NBC News asked UnitedHealthcare and the Public Employees Insurance Agency a series of questions about Eric’s case, the agency backed down. PEIA decided to cover his treatment.

Notably, the agency contacted KFF Health News about the approval hours before informing the Tennant family of the decision.

But the approval came too late. Eric was hospitalized in late May and prescribed medication that prevented him from undergoing histotripsy at that time. His family hoped his health would improve and he would be eligible for the procedure that summer.

In July, they took a family vacation to Marco Island, Florida. It would be their last. Two days after they returned home, a scan revealed that Eric’s cancer had continued to spread. Histotripsy was out of the question.

“I’m sad about what we’re going to miss,” Becky said. “I am saddened by this injustice.”

She said if Eric had been able to undergo histotripsy in February, as his doctor had initially recommended, it could have destroyed the tumor in his liver that ultimately killed him.

“We’ll never know. That’s the problem. Any insurance lawyer will say, ‘Well, you don’t know that would have helped.’ No, you took that chance away from us,” she said.

In October, Samantha Knapp, a spokeswoman for the West Virginia Department of Administration, told KFF Health News that the Public Employees Insurance Agency has not changed its policies regarding prior authorization for histotripsy and continues to follow UnitedHealthcare guidelines.

UnitedHealthcare declined to answer questions for this article.

On September 17, in a hospice bed set up in their dining room, Eric was surrounded by his family and their dogs as he died. Becky held his hand as his heart rate began to drop.

“He wasn’t afraid to die, but he didn’t want to die,” she said. “And you could tell on the last day that he was fighting hard.”

At the very end, she whispered in his ear, “You know I love you. You were the best husband and the best father, and you always took such good care of us,” Becky recalled.

And then, she said, he gasped. His eyebrows seemed to raise in wonder. During his last moment alive, she said, he smiled.

“The look on his face was pure and utter astonishment,” she said. “I still can’t believe he’s not here.”

Do you have a prior authorization experience that you would like to share? Click here to tell your story to KFF Health News.