Evidence of ancient life on Mars could be hidden away in colossal water-carved caves

When you purchase through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

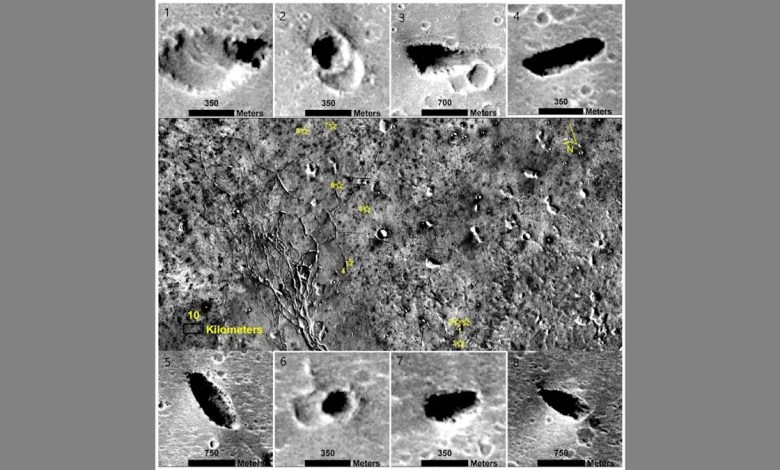

Images of the eight skylights opening onto possible karst caves at Hebrus Valles on Mars. . | Credit: Sharma et al (2025).

Possible giant “karst” caves that formed when slightly acidic water dissolved bedrock have been identified on Mars and hailed as one of the best places on the Red Planet to search for preserved biosignatures.

“With the technological advances expected in the coming decades, if missions are specifically designed for these targets, we believe that in situ exploration of Martian karst caves is an achievable goal,” said Chunyu Ding, of the Institute for Advanced Study at Shenzhen University in China, in an interview with Space.com.

The caves, in the Hebrus Valles region, between the extinct volcano Elysium Mons and Utopia Planitia In MarchMid-northern latitudes are revealed by eight skylights, which are holes in the cave ceiling visible on the surface as pits ranging from several dozen to over 100 meters in diameter. Skylights are distinguished from craters because they do not have raised walls or ejecta splashes around them. The skylights are thought to form when the surface partially collapses into the empty cave below.

Caves and skylights have already been discovered on Mars, but as lava tubes formed volcanic regions. Hebrus Valles, on the other hand, is not a volcanic region; it features ancient river channels and numerous minerals and hydrated sediments deposited by bodies of liquid water to the surface a long time ago.

These features were identified by scientists led by Ding and his Shenzen colleague Ravi Sharma. Their team used archival data from various missions to Mars, including mineralogical maps based on observations from NASA’s now-defunct Thermal Emission Spectrometer. Mars Global Surveyorhydrogen detections (as an indicator of water) from the Gamma rays Spectrometer on the agency website Mars Odysseyand models of the Martian terrain built around data from the NASA satellite’s HiRISE camera. Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

They determined that the skylights and their surroundings correspond to what are called “karst” caves. Karstic refers to the dissolution of carbonate and sulfate bedrock. Although karst caves are found in many places on Earththis is the first time they have been identified on Mars.

A cutaway diagram showing a skylight and an underground cave on Mars. | Credit: Sharma et al.

Observations show that the Hebrus Valles region is rich in carbonate rocks like limestone and sulfate rocks like gypsum. More than 3.5 billion years ago, when Mars was warmer and wetterthese carbonate and sulfate sediments were deposited by large pools of liquid water, such as lakes and seas. As Mars cooled, surface water disappeared, much of it forming subsurface ice and frozen brines.

Indeed, data from Mars Odyssey’s gamma-ray spectrometer indicates that water ice may still exist there in some quantity. At some point, local warming events, perhaps due to distant volcanoes, impacts, or long-term orbital variations, would have melted subsurface ice and brines, and liquid water would have flowed through cracks and fractures in the ground, dissolving rock and turning these cracks into large caves.

Not all regions of Mars qualify for karst caves, as carbonate and sulfate rocks are not ubiquitous. Nor do all places, especially low-latitude areas, harbor subsurface ice and frozen brines, nor have they been geologically stable long enough to allow caves to form and their rock ceilings to collapse and form skylights.

“Our results suggest that Hebrus Valles is unlikely to be a completely isolated case, but these caves will not be present everywhere on Mars either,” Ding said. “They are likely concentrated in a limited set of regions that meet the necessary depositional and hydrological conditions. It is entirely reasonable to expect that more karst caves will be discovered in other similar environments in the future.”

Indeed, Hebrus Valles is not limited to the eight caves; there could be others who have not yet experienced the ceiling collapse and have not yet revealed themselves. Among those known so far, the skylights appear to have a diameter of several dozen to more than 100 meters, and underground, the cavities could be even several times larger and reach tens of meters deep.

Karst caves are the ideal place to preserve ancient biosignatures. The caves’ stable, watery microclimate might once have supported microbial colonies, and today the caves are protected from extreme conditions on the surface of Mars, such as wildly different daytime temperatures, dust storms, and solar and ultraviolet radiation. cosmic ray radiation. So future life search missions may seek to explore them.

However, the surrounding rock will limit the transmission of radio signals from inside the caves to orbiting spacecraft, making exploration of the caves more difficult, but not impossible, Ding said.

“From a technical point of view, going directly into these caves is a major challenge,” he said. “However, our geomorphological analysis suggests that not all candidate caves are simple vertical shafts. In our paper, we use the term ‘potential accessible karst caves’.”

Most skylights are characterized by steep walls descending into the darkness of the caves, but among the eight caves of Hebrus Valles there is evidence of slopes consisting of rock debris in multiple step-like formations that could allow step-like descent.

This could be accomplished by multiple robotic explorers forming a communication chain in the caves, ranging from wheeled rovers that carefully descend each step, to climbing robots lowered by winches or aerial rotorcraft who can enter and exit the skylights.

The cave’s rock shielding could not only lend itself to preserving biosignatures, but could also offer protection to future Martian astronautsprotecting them and their outposts from the dangers of radiation and dust storms on the surface. If so, it could be that humanity’s future on Mars lies underground.

Ding’s team’s findings were published October 30 in Letters from the astrophysical journal.